R.I.P. Dmitri Vrubel, artist, pirate and start-upper

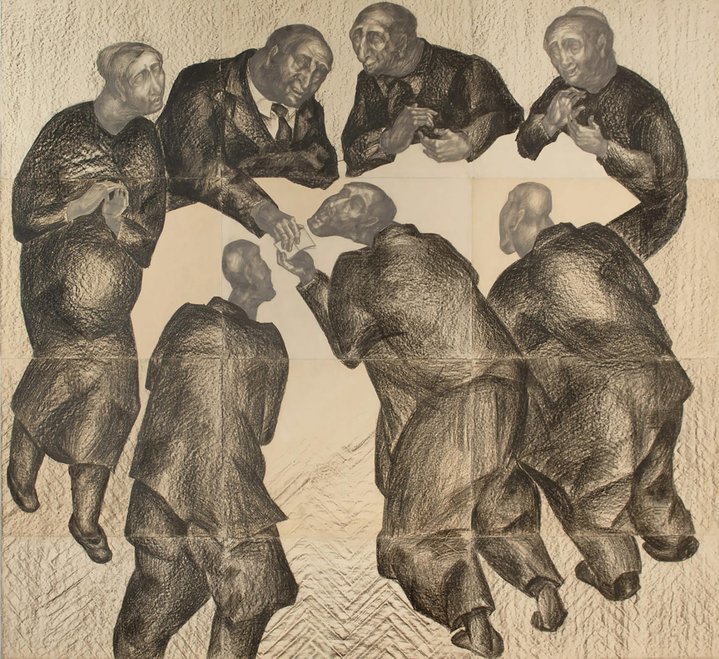

Dmitry Vrubel, Victoria Timofeeva. New Testament Project, 2008

Russian artist Dmitri Vrubel, best known for his iconic mural on the Berlin wall of Brezhnev and Honecker kissing, has passed away at the age of 62. Art critic and collector Vladimir Dudchenko remembers his encounters with this contemporary legend.

I got to know Dmitry Vrubel (1960–2022) on Facebook in early 2013 when he was staging mini online auctions of his own graphic works together with his wife Victoria Timofeeva. Out of curiosity, I wrote enquiring about such prosaic details as the edition number, invoicing and delivery, and he replied to me directly. Because of this, I won, paid for and then received three or four of these works executed in mixed media with collage, photo and ink drawing.

This auction initiative brought out several of Vrubel’s character traits. Firstly, his desire and ability to paint and draw. Secondly, his deep mistrust of any galleries and an anarchistic desire to sell everything by himself and “not to pay any commission to a dealer”. Finally, his use of images from news feeds and the internet.

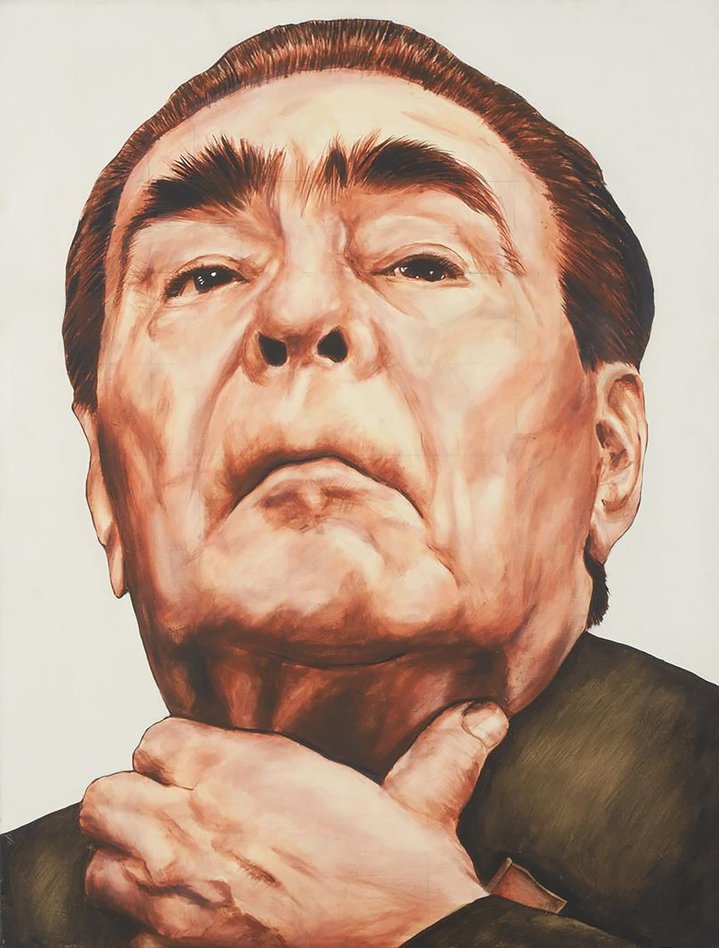

Let's begin with the last of these, the news agenda. Vrubel's most famous work nicknamed, ‘The Brotherly Kiss’ (1990), graffiti on the wall dividing Berlin, for which he used a photograph from 1979 as his source material, is almost media archaeology. That is, he didn't draw generalised images, he drew pictures taken directly from the TV, later from the internet. Back in the early 80s, Robert Longo (b. 1953) did charcoal drawings in the same way, taken from photographs and the screen. However, I don’t think Dmitri was concerned with the production of an image like the post-modernists, rather it was more about a desire to capture the everyday, to express something about the current moment in time using the most fitting image. For this to happen, you need to be clear about where your emphasis is, shifting scales, to provide a succinct explanation to the dialectically opposed image.

This was the case with Vrubel and Timofeeva's ‘Evangelical Project,’ which was shown at Art Moscow in 2008 in the non-commercial section of the fair, and a year later in the PERMM Museum. Photorealistic images of people in a state of decay, printed with acrylic on PVC, they were huge, three metres high with quotations from the New Testament. The people were thugs and criminals found on the vast expanse of the Russian internet. This exhibition was nominated for the Kandinsky Prize and art historian Boris Groys wrote a good text about it. And then it was kept in storage in the city of Perm for another nine years, until enthusiasts from ‘In Situ Society’, a non-profit organisation, received a special grant to bring it to Germany. As a result, its next destination was the former St. Elena's Church in Bonn in 2018. And this chasm between fame and sales was a trait of Vrubel, the anti art gallery warrior. He continued partisan activities for at least the past 15 years and it suited him perfectly. Vrubel was once a member of a Pirate Party in Berlin, and he even looked like a pirate, all alert and acerbic, with a bristling moustache.

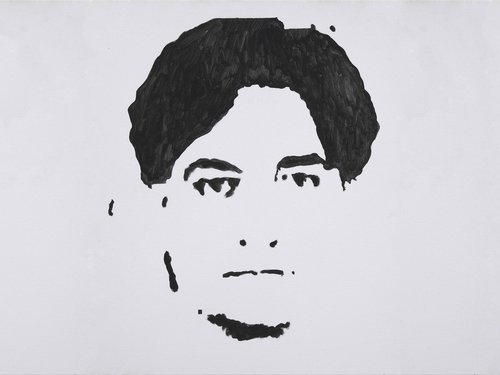

Throughout their working lives together Dmitri and Victoria sought to adapt their art to the news agenda. In 2001, they made a calendar with twelve pictures of newly elected President Vladimir Putin which was presented at the Velta Gallery in Moscow. Why portraits of him? Because that was the “Who is this Mr Putin?” at the time, a newly dominant face on TV. Later, in 2014, there was an exhibition at the German embassy in Moscow about Frau Merkel.

And in 2015, we saw each other in Berlin. Vrubel and Timofeeva had almost turned the Panda Theater in the grounds of the Kulturbauerei in Kreuzberg into their own studio and exhibition space. It was certainly an inspiring place to visit, and Dmitri spoke passionately about the city and how to make it work for him, and about his rational decision to move there. On this visit I was in Berlin for the first time in 15 years, and that conversation, to a large extent, influenced my own personal life choices and probably those of dozens of other friends and acquaintances.

By the early 2010s Vrubel was a big personality on social media: he would react instantly to comments, pour venomous ridicule on critics, and in the spirit of a rap battle always asserted the superiority of his position, whether in politics or art. According to him, he was Berlin's most famous artist, and needed no intermediaries, after all on the internet he was in direct contact with his clients. His ‘Kiss’ was the symbol of a united Berlin. The rights to this image are in the public domain which applies to graffiti art in general. He had 30,000 followers and if just one percent bought something from him, that was already 300 sales!

At meetings he would talk with enthusiasm about his plans for collaboration or partnership, and, to his credit, was never embarrassed by failures. Such is the temperament of a real start-up entrepreneur, someone always dreaming up the next killer app.

His next big project was ‘Tolstoyevsky’. Vrubel announced that there are only two Russian writers who can be called truly global: Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy, with all others falling short. A huge number of calluses on the internet were trodden away after that. Next, on the internet he and Victoria created a series of portraits of all kinds of people on the scale of their earlier Evangelical Project. It was ready-made material for memes, from police officers to the socially irresponsible public. And these portraits became illustrations of these two Russian classic writers. But was only part of it: they went on to create a special way of hanging and narrative demonstration of artworks, a bit like a theatre which let you somehow live through one of the novels, or the mix of several ones. It was actually on the scale of a museum project but although many curators and old acquaintances saw it, the work was never shown in a museum. And then they had to leave the Panda which was in many ways inevitable. They had nowhere else to show these kind of projects.

However, Vrubel then discovered the world of virtual reality. From this he went on to practically negate art existing in the form of temporary exhibitions bound by the laws of space and rent. He believed the entire treasury of visual culture should and would be digitised and preserved forever on the vast expanse of the internet. That every museum had to transfer all of its exhibitions immediately into VR. And so, in 2019, just before the iron curtain of the pandemic, I visited the Vrubels and enjoyed a complete demonstration of exhibition spaces already created by their family firm. At the same time I took a course ‘for young fighters’: I used VR goggles for the first time in my life, and Dmitri told me that this is generally the only investment people need to make nowadays. He saw on-screen forms of communication as so 20th century and was of the view that all the young and technologically advanced have been communicating that way for a long time already. He believed there would be no cinema, no television, only VR…

And then due to the pandemic all travel between cities became almost impossible, and when I moved to Berlin, there was no time to meet up. But after the outbreak of the conflict in the Ukraine and the bombing of the cities, we all, thousands of friends and followers, read and liked the Facebook thriller ‘Saving Private Mother-in-Law’, a series of Dmitry's posts about the evacuation of Victoria's mother from Odessa. And she was rescued, and taken to Berlin via Romania and Paris. That has only just happened.

The last work by Dmitry Vrubel and Victoria Timofeeva that I saw was ‘Bunker’ as part of the Cha Scha, a land art exhibition near Moscow in 2020. The entrance to this work is down a flight of steps, beneath the surface of a rather benign September forest. Inside, however, there is a very different reality. The setting is ragged, and the entire space from floor to ceiling is covered with pictures of our valued politicians rendered in brown. The other side of fun and joyful life contrasting particularly with the benignly apolitical public art of the other star participants.

And the smell of fresh earth.