Repin's Boat-Towers keep towing on

Ilya Repin. Boat-Towers on the Volga. 1870–1873. The painting, part of the collection of the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, is one of the highlights of the current Ilya Repin exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery

A blockbuster solo show of the Russian classic Ilya Repin (1844–1930) is now on view at the Tretyakov Gallery. Repin’s oeuvre is still relevant today, as proven by the numerous interpretations of his iconic masterpiece “Boat-Towers on the Volga” in contemporary art.

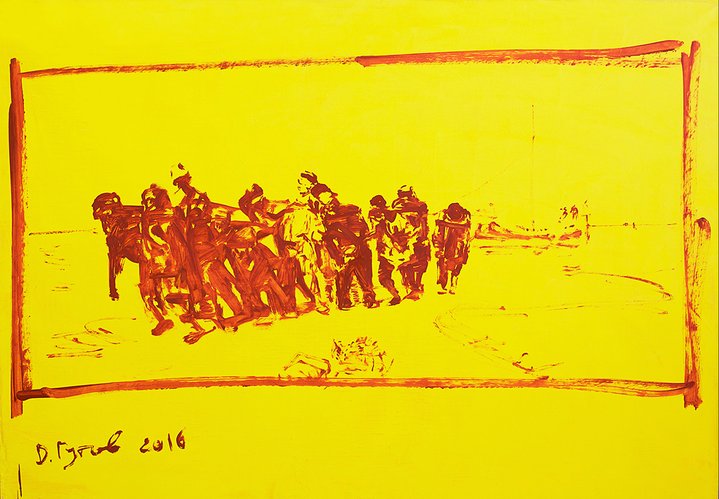

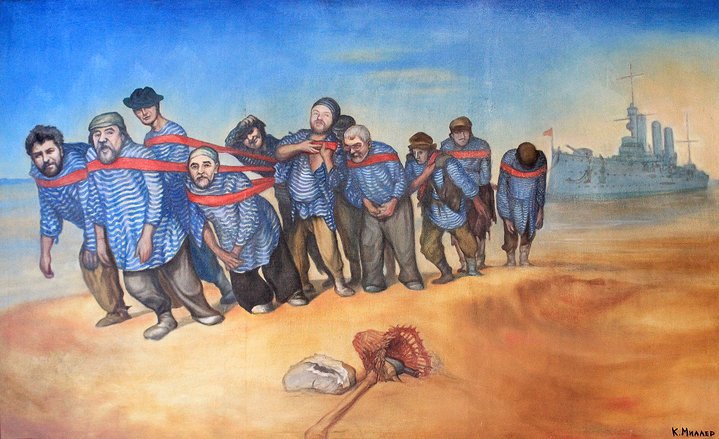

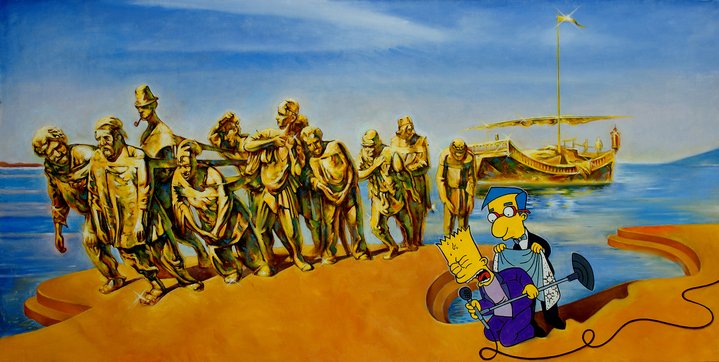

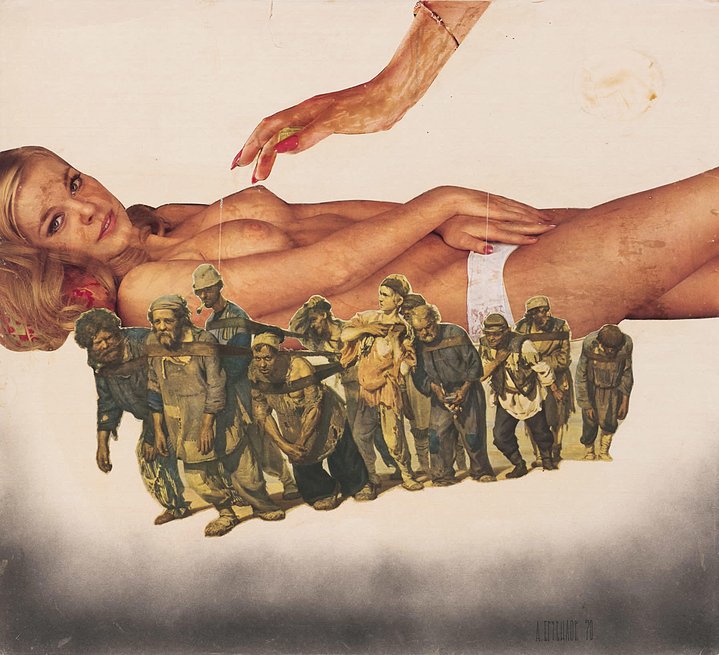

Whenever one thinks of realism in 19th-century Russian art, the name Ilya Repin is the first to spring to mind. He was equally strong in portraiture, historical painting and dramatic depictions of contemporary life. “Boat-Towers on the Volga” (1870-1873), finished soon after his graduation from the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg, was his first major work dedicated to the poignant issues in the society of his time. Repin became interested in the subject after seeing boat-towers on Neva River that flows through St. Petersburg. He began working on the sketches for the painting during a steamboat trip along the Volga, which he took with two fellow artists in the summer of 1870. In the age of steamboats, the use of humans as draught animals was already considered the epitome of barbarism and exploitation. Boat-towers were the outcasts of society and often had criminal records. Repin depicts these downtrodden victims of social inequity as human beings possessing their own individuality and dignity. Due to its unglamourous subject matter, the painting caused a mild shock when first exhibited. Yet it was acclaimed by critics at the time and was later much favoured by the machine of Soviet propaganda. In the Soviet era, reproductions could be found in primary school textbooks, making the painting a familiar sight for every child. It was used to show how dreadful the life of common people had been before 1917's October Revolution, as opposed to the prosperity the masses supposedly enjoyed in the USSR. However, while the comparison might have impressed primary school students, more mature minds could instantly feel its blatant hypocrisy. Life in USSR was no less harsh than in Tsarist Russia, and millions of innocent starving, cold GULAG inmates were doing hard physical labor no less grueling than Repin’s burlaki — who were at least paid for their work. Repin's easily recognizable composition was often re-worked by anti-establishment artists in an ironic or sarcastic way. This tradition is alive even now, long after the collapse of the Soviet empire. The Communist system may be gone for good, but the ideological clichés and counter-clichés of the time are not so easy to erase from cultural memory.