Naum Granovsky. Shukhov Tower, 1929

Rediscovering Post-war Soviet Photography

A new publishing initiative by Moscow’s Lumiere Gallery on post-war photography is aimed at both Russian and English-speaking readers, focusing on the Thaw and everything that happened after it.

For most people, Soviet photography evokes predictable images of Stalinist documentary reporters. Military parades and marching athletes, workers carrying out five-year plans, products of industry in abundance. However, a new joint project between the Lumière Brothers Center of Photography in Moscow and the Still Art Foundation sheds light on (until now) lesser known photographers of the era, who turned their camera away from the public to the private, to focus instead on the intimacy of every day life.

The project started out with the work of Alexander Rodchenko, Russia’s greatest pre-war photographer. Despite belonging to an earlier generation, he is considered too critical a figure to be omitted (there is also currently a Rodchenko exhibition curated by the Still Art Foundation on display in St. Petersburg’s Radio House until January 9, 2022). However, the project’s mission is to present post-war photographers, with an emphasis on those who started out and became known during the Khrushchev Thaw. It covers the 1970s and 1980s and stretches into the early post-Soviet period also, so it’s not short on scope.

Nowadays, publishers interested in the field of Soviet Photography are playing catch-up across Russia and other countries of the former Soviet Union, notably Belarus, Ukraine and Lithuania. Publishers such as Gusev’s Treemedia, Andrey Naslednikov and Cloudberry are bringing forth experimental books by pioneering writers in the field and are publishing new research on the history and theory of photography. Add to this the activities of the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow (MAMM), which produces scholarly catalogues of its Photobiennales and exhibitions, as well as the series ‘Russia in the 20th Century’ and there is a new critical mass of scholarship in the field.

The archives of Moscow press photographers provided a rich source of material for the Lumiere Gallery’s initiative, supplemented by the photographers themselves or their family. The choice of images included in each publication is largely determined by the holdings of the prints and negatives in storage, shaped further by an editorial vision based on the narrative threading through successive exhibitions. Founder and director of the gallery, Natalia Litvinskaya, explains their unique appeal: “As a community of photographers and art critics, we have done almost nothing to tell the history of Soviet photography from the 1960s onwards and there is a reason why books that have already been published get sold out very quickly. It’s because a lot of people didn’t see their work and are unfamiliar with it, especially in the West, because the Iron Curtain was between us. Of course, it’s ridiculously interesting.”

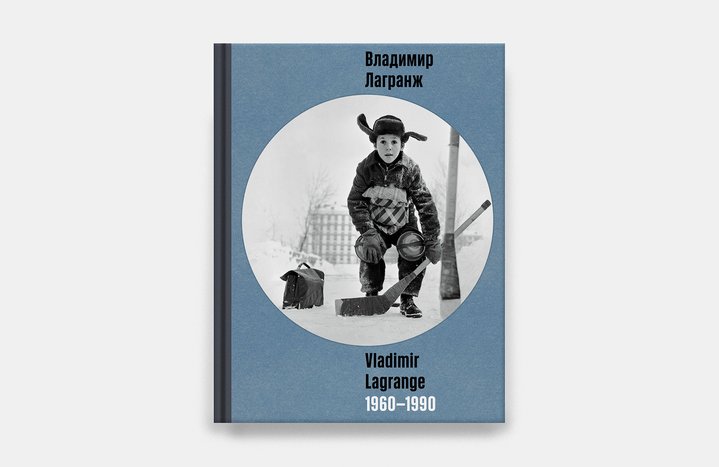

Although it’s one series, all the books published to date are very different. After decades of Soviet attempts to line everyone up to a common denominator, this lack of diversity is refreshing. From 1928, the Stalinist legacy marginalized all genres, except the bravura of socialist realist reportage, a situation which only began to melt at the edges during the Thaw. Even today, these publications continue to push the dial yet further away from the legacy of Stalinism. One of the most interesting and groundbreaking volumes to appear is about Vladimir Lagrange (b. 1939), its foreword by critic and photography historian Mikhail Sidlin.

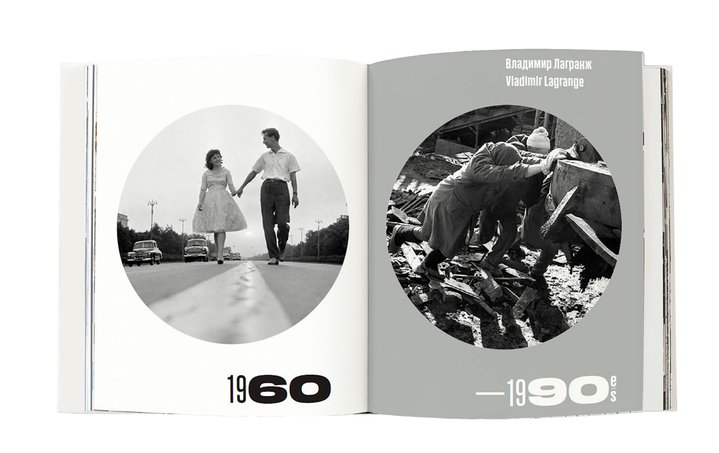

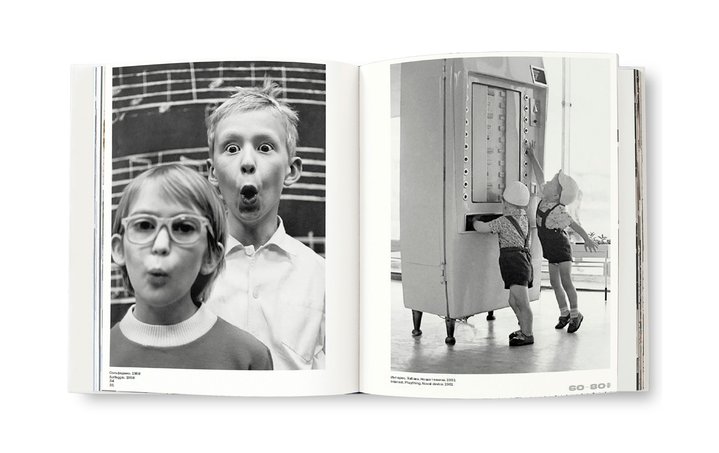

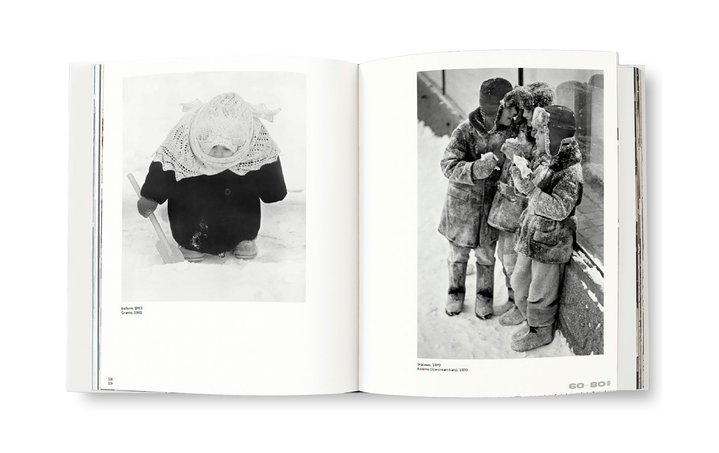

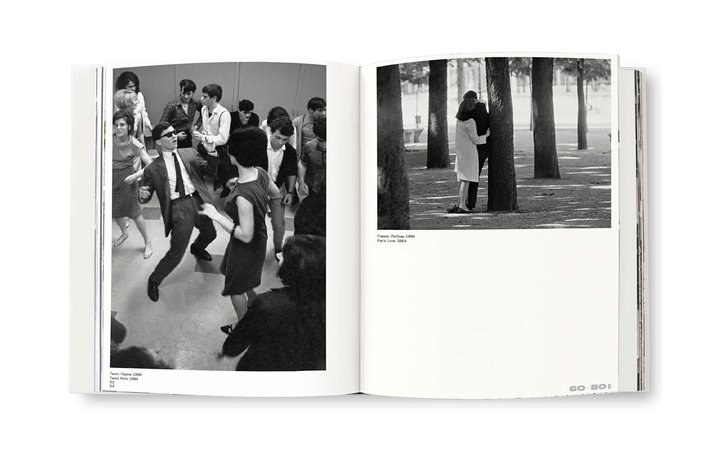

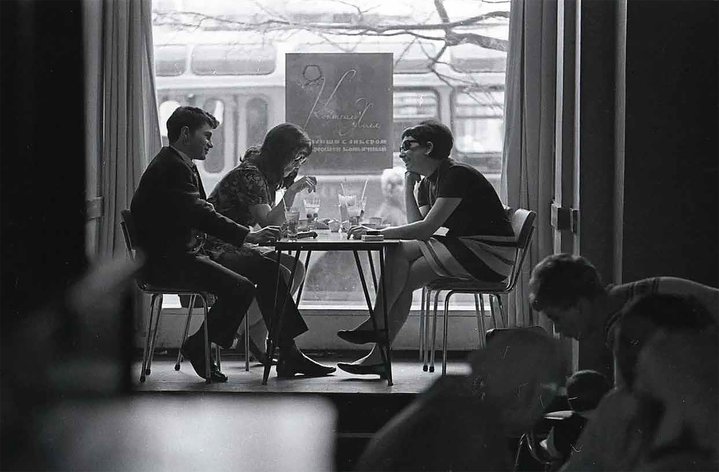

Lagrange pioneered what came to be called the ‘Minor Alternative’, a less rigid and softer picture of everyday life, which emerged in the press during the Thaw and in the early Brezhnev years. These works reflected simple human emotions: the infectious laughter of children throwing snowballs in winter or playing hockey. Babies wrapped up in their grandmothe’s shawls, girls blowing a dandelion and rebellious boys at the classroom door or skipping school to eat ice cream. There is also a well-loved image of a young pioneer, who is yawning at a parade, something unthinkable twenty years earlier. There are sportsmen and women and students, young lovers on the street, an old women in the countryside. Factory workers, harvest scenes, machine operators and oil workers. All of these images are captured, in the words of Lydia Dyko, an authority on photography of the era, as “reportage portraits”, fusions of “document and poetry” with “live contacts”, in which “the person is no longer separated from the viewer by the barrier of professional photographic techniques”.

The subjects of these images are always smiling, they look friendly and attractive. There are heroes of the intelligentsia of the Thaw of the 1960s, poets Andrei Voznesensky and Yevgeny Yevtushenko and the theatre director Yuri Lyubimov. Lagrange became famous for these images when, at the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s, he began working first for the state news agency TASS and then for the Soviet Union magazine. Alongside this are his shoots of Parisian streetlife in the 1960s, which echo the French “humanist” photography of Robert Doisneau and Henri Cartier-Bresson, as well as ‘The Family of Man’ by Edward Steichen ( who incidentally visited Moscow in 1959). Like their Western counterparts, accused of a lack of social engagement after the events of 1968, Lagrange and his generation can be critiqued for omitting the other, less optimistic sides of reality and becoming clichés – and this at the end of Brezhnev’s ‘stagnation era’. In spite of this – or maybe because of it - you can feel a kind of nostalgia for this lost world of imagined equality and warm co-existence with our fellow human beings.

All of a sudden, however, in sharp contrast to the rosy pictures described above, you encounter completely different, quite unexpected images. Many of these were shot “off record” and have been unveiled only at recent exhibitions, or have never before been published and are something of a revelation. They are not marginal: this body of work occupies nearly half of the book. There are images of tired Soviet citizens voting unanimously, but thinking about something else entirely, such as the 1982 photograph ‘Always Pro!’. Participants leaving a parade or demonstration with a huge portrait of Lenin; Communal flats and their hard life captured in various images during the 1980s and 1990s. Women engaged in hard labour and laying railway lines such as in ‘And Men Have Other Work’ (1982), and ‘Easy!’ (1984). The end of the war in Afghanistan depicted in ‘Requiem’ and ‘A Heavy Fate’ (1989). Difficult rural life and ruined villages. All subjects the Soviet authorities had considered not suitable for public consumption at the time. There are shots of the victims of 1937 and then the putsch of 1991 and the collapse of the USSR. In these images Lagrange even appears close to the circle of unofficial artists active in the Soviet period.

In the USSR, people practicing the medium of photography, as well as the proponents of the so-called “straight look” in documentary photography were pushed out of professional spheres into what was deemed to be “amateurism”. In the 1970s and 1980s, they created a parallel public sphere in Russia and in doing so laid the groundwork for perestroika. Alexander Slyusarev (1944–2010) and Yuri Rybchinsky (b. 1935) in Moscow, Lyalya Kuznetsova (b. 1946) in Kazan, Yuri Shpagin (1939–2006) in Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod), Valery Shchekoldin (b. 1946) in Ulyanovsk, Evgeny Likhosherst (b. 1949) in Cheboksary and countless others who worked in different parts of the Soviet Union. Their work completes reality, but it was not a “Socialist” one. Paradoxically, despite perestroika, some of their work is still locked up in the archives, as if today we are repeating Soviet censorship. It transpires only now that Lagrange also shot a lot of things that could not be printed, images he made for himself only, without the dictate or blessing of editors and, even after 1985, they did not come to light until recently.

The volume dedicated to photographer Naum Granovsky (1910 –1984), with a preface by Elizaveta Likhacheva, director of the Shchusev Museum of Architecture, is completely different from that of Lagrange. This is a voluminous, detailed catalogue of this “Moscow chronicler”, which was released on the 110th anniversary of the artist in 2020. The images included in the book had been painstakingly selected from an archive of some 35,000 negatives and catalogued by the family of the photographer. The amount of work it took to complete this volume is palpable. For six decades, from the 1930s to the 1980s, Granovsky photographed Moscow in black and white. His work is seductive, they are powerful images which literally reel the viewer in, making them stick like a fly in amber. There is a feeling that their monotony could be reduced further by more focussed editing. However, what looks like a relaxed and meditative stroll with some constant to-ing and fro-ing to the same points of reference in the city turns out (when you peer closely) to be a not so innocent pleasure of pure architectural shooting. Here and there, signs of different eras break through: the demolition of a pre-revolutionary town and the construction of the Stalinist Empire, queues standing in mausoleums or Khrushchev-era residential blocks, which allowed people to get out of a barrack, but are so ugly in appearance. At times, Granovsky appears to take on the guise of reporter and researcher at the same time. He treats the smallest signs of time as a neutral passage, with Olympic calm. And yet, this is most definitely a human gaze, one that is humane and this allows us - thumbing through the pages - to sympathize, to experience, to add the historical context with our imagination, to celebrate life, or to feel an echo of a distant tragedy.

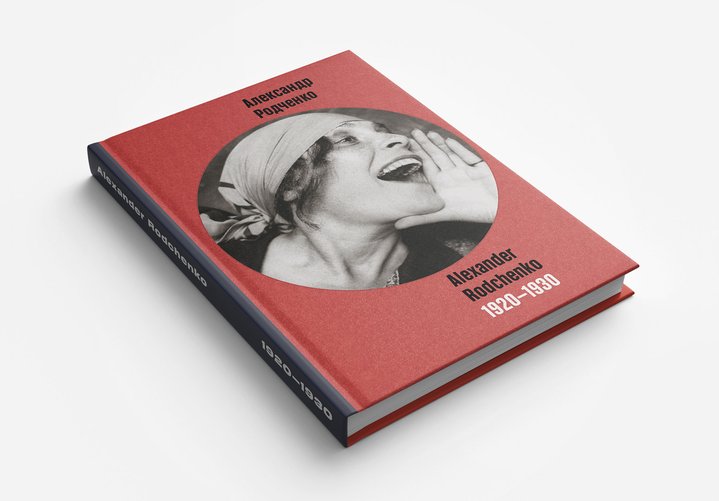

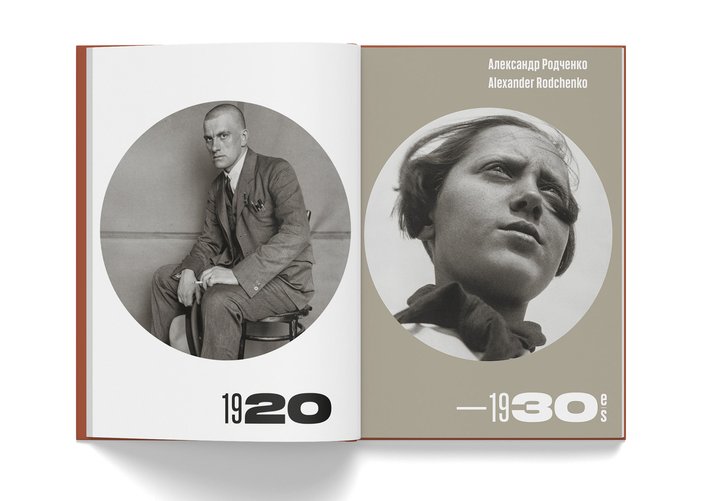

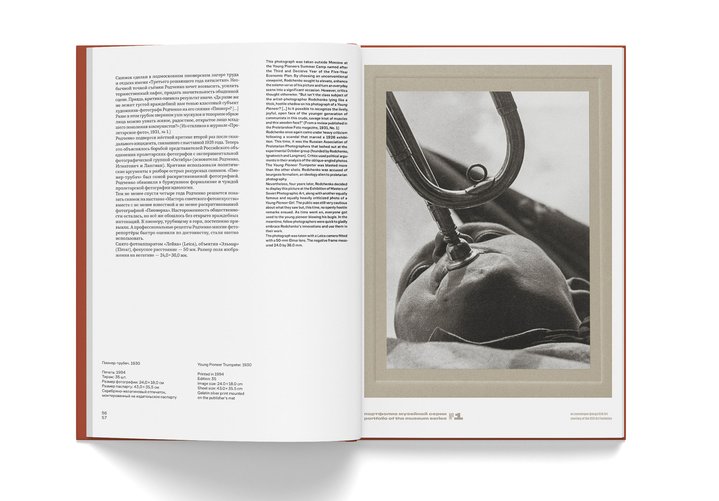

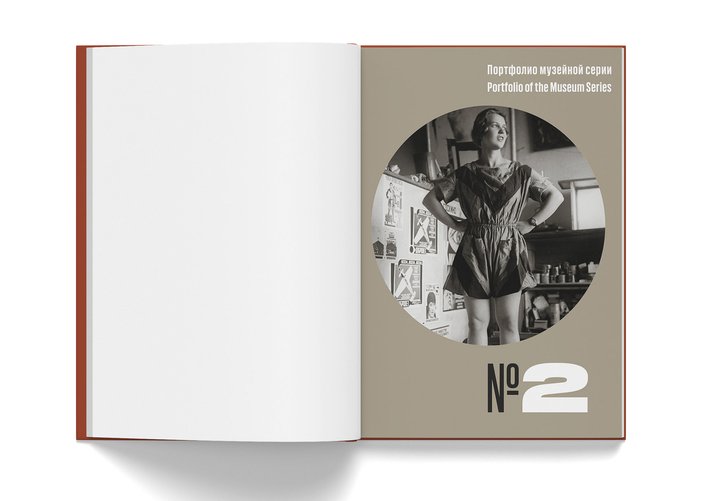

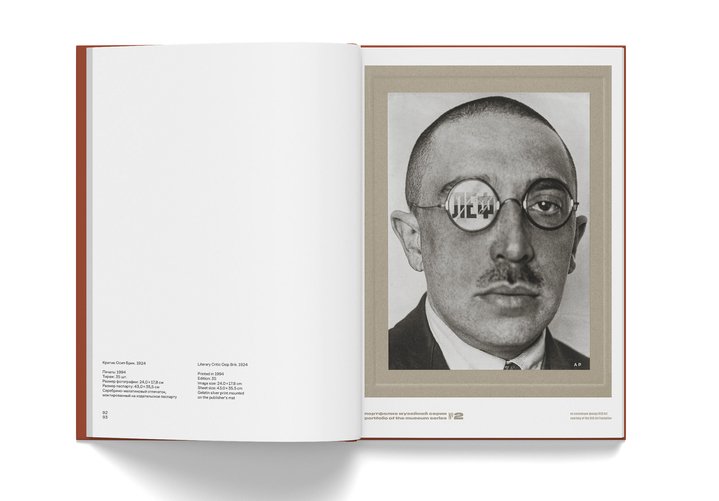

Finally, there is an illustrated album by that inimitable master of photography, Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956), famous for his avant-garde angles and other constructivist experiments with form. Ironically, this is the smallest volume in the whole series. The new book is a sort of a beginner’s ABC of his most famous shots, rich in additional information and a good re-publication of the two so-called ‘Portfolios of the Museum Series’. Rodchenko, as well as his wife, artist Varvara Stepanova (1894–1958), repeatedly made well edited cuts of his work throughout his life, constructing and modeling a biography of sorts. But the portfolios themselves refer now rather to the history of the nineties, when, together with the Howard Schickler Gallery, Rodchenko’s heirs planned to make a series of such publications for universities and museums, calling them the ‘Study Collections’. Only two came out, the ‘Classics’ (Rodchenko’s most recognizable images) and ‘Alexander Rodchenko and His Circle’ (portraits of contemporaries), which are reproduced in the album, with a foreword by the author’s great granddaughter, the art critic Ekaterina Lavrentieva. A third portfolio of unknown works was never made. Revved up by perestroika, the interest in the Soviet photographic heritage faded away towards the end of the nineties, both in Russia and abroad.

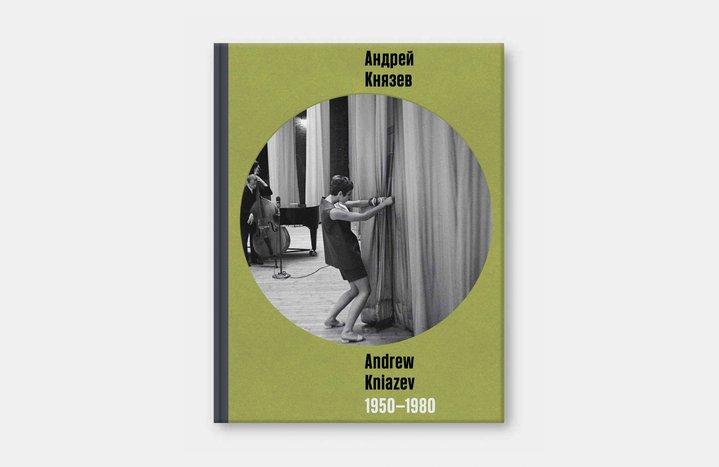

It is only now being revived. Litvinskaya says there are two more volumes to be published, dedicated to the photographer of Soviet Screen magazine and Moscow News newspaper (until the end of perestroika) Andrei Knyazev (1932–2003) and to Vladimir Stepanov (b. 1940), a street photographer and chronicler of daily life of Moscow and Muscovites. Their archives were researched by the Lumiere Gallery for ten years: “Of course, if you start to sort through the negative archives, you find a completely different face, a different author, different views. As in the case of Lagrange, who also filmed informal Moscow, informal Russia.” This process of revision of late-Soviet photography is deliberately undertaken by the museum and it can be noted that its exhibitions and editions have become much more interesting, historically accurate and bolder over the last decade. Litvinskaya attributes the switch of interest from the avant-garde to the 1960s-1980s to a desire to satisfy the domestic audience’s thirst for knowledge, to new Western interest, which she already noticed at the Houston Festival in the early 2010s, and now at Paris Photo, and to the development of the market. The latter is linked to the change of epochs: among collectors, the generation of 35-45 year olds, who no longer “feel, see, understand” the 1930s, has come to the fore. All the more so, because it is almost impossible to find good new Rodchenko works. These people are more interested in the 1960s-1990s, where discoveries are still possible.

In fact, both the publication of Rodchenko’s portfolio and the painstaking work with the Lagrange and Granovsky archives are a reflection of a changing landscape with its renewed reflection on the history of photography. This slowed down in the 2000s, when older photographers often dropped out of the public eye, while the youth of the day expressed no interest at all in the Soviet times. Nowadays, the photographers of those epochs, all over the post-Soviet space, are actively revising the archives of their works and publishing new books. Among them are not only people from St. Petersburg and Moscow, like Igor Mukhin (b. 1961), but also, for example, Ryazan photographer Andrei Karev (b. 1961), previously known for his formal experiments, but who just published a photo-book of unknown documentary works from 1980–1990. Or Cheboksary resident Yury Yevlampiev (b. 1954), engaged in making a history of photography clubs’ movement of the 1970s-1980s. The new interest of millennials for perestroika and not only in photography can be put into the same box. In general, the recent polarization of those with a euphoric nostalgia for the USSR and its opponents is being replaced by more careful and subtle interpretations. The main aim is to work on the distinction between eras, communities and meanings.

Lumiere Gallery Publishing Programme:

Alexander Rodchenko 1920–1930

Vladimir Lagrange 1960–1990

Naum Granovsky 1920–1980