Pivovarov and the Colours of the Human Soul

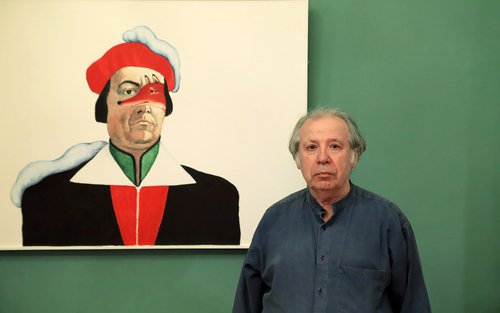

Viktor Pivovarov at ‘Metaphysics and Despair’ exhibition. Photo by Tomáš Cindr. Courtesy of DOX Centre for Contemporary Art

‘Metaphysics and Despair’ a solo exhibition of work by Moscow Conceptualist Viktor Pivovarov at the DOX Centre in Prague is an opus of visual philosophy depicting a poetic journey of the creative spirit through a world engulfed in madness and brutality.

In 1937, Daniil Kharms wrote down in his notebook his thoughts about the symbolism of colour, associated with the rise, fall and destruction of the human soul. Kharms was a follower of Malevich (1879–1935), he was attracted by the art of Suprematism, elements of which are often reflected in his texts. In Kharms’s work, one can find many similarities with the philosophy of Henri Bergson, especially his theory of knowledge, memory, the understanding of consciousness and creativity, as well as the concept of time.

In the same 1937, artist Viktor Pivovarov was born in Moscow. Since 1982, he has been living in Prague, and a solo exhibition ‘Metaphysics and Despair’ at the DOX Centre for contemporary art builds on the study of the discoveries by Kharms, Malevich and Bergson. The world is in perpetual motion, it is almost impossible to keep track of it, and only poetry can encompass what is inaccessible to the mind. In a cycle of artworks that gave the exhibition its name, Pivovarov answers the eternal question is poetry “after Auschwitz” possible?

Despair (newspaper headlines about the deaths of civilians and destruction in Ukraine) is accompanied by metaphysical drawings that look like puzzles in the spirit of Giorgio De Chirico (1888–1978). Pivovarov often quotes René Magritte (1898–1967), we see a mysterious stone, the ultimate object. “A stone, which does not think, thinks the absolute.”

Like Magritte, he uses the principle of colossal enlargement of objects in comparison with the small figure of a human being. In the painting ‘Depression’ (2024), almost the entire room is occupied by a black shoe, towering over the bed where a tiny man is lying in despair. Pivovarov singles out one painting: the portrait of a man who appears dissatisfied, with rabbit ears and a white, blue and red face – the colours of the Russian flag. In another work from this cycle, a red-eyed rabbit walks towards a man in a suit, a naked soul sitting on his shoulders, a reference to the famous monument to Kafka by Jaroslav Róna (b. 1957). Perhaps this sinister rabbit is the embodiment of the anxieties generated by the artist's homeland.

This somewhat autobiographical cycle presents inspiration´s varied forms and paths and depicts all the possible hardships and joys associated with the creation of a work of art, be it literary or visual. With insight and humour, it shows how complex and arduous the birth of these uplifting metaphysical works is and what kind of mental and physical anguish it involves.

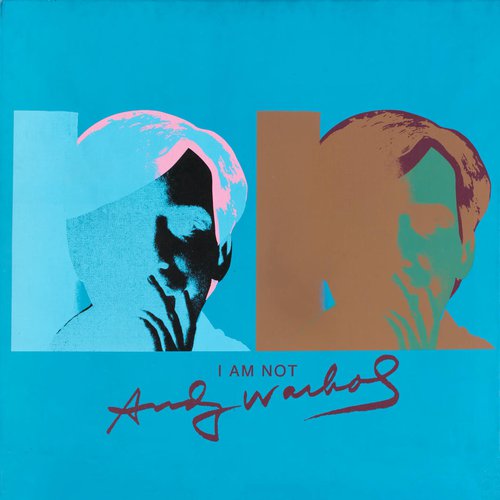

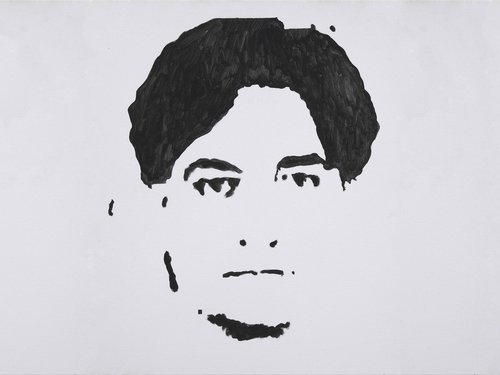

Abstract compositions from the album cycle ‘To the Philosopher, Letter No. 3’ (2005) illustrate the secret symbolism of colour described by Daniil Kharms where blue is the colour of reason, green is the colour of the soul, orange is the colour of the lower instincts. “This album is about what happens to the human soul if it is affected by various components. If it is spiritual, it will rise, but if it is too carried away by reason or base human instincts, the soul will fall either into hot flames or the abyss,” explains the curator of the exhibition, art historian Masha Pivovarova the artist’s daughter and curator of the show. In the work ‘Blind Fury’, orange predominates, in ‘The Soul Wants Vodka’ it is green. Two self-portraits also belong to this cycle, ‘Poet and Muses’, in one of them the artist's double is clutching his ear (both are green, the colour of the soul). In another self-portrait his hero (green again) has abstract figures dancing in his head. The world with its nightmares and anxieties is transformed in the creative mind into incomprehensible squiggles and figures. As Kharms wrote: “I took the ball out of my head.”

In the painting ‘Poet and Objects’, a small man sits at a table on which are a huge mug, a giant egg, a baguette and a spoon – once again a reference to Magritte, illustrating the artist’s fascination with the incomprehensibility and diversity of the objects he depicts. “I am visited by the muses of poetry and art. The muse representing painting often reminds me of my mother,” says Pivovarov, who is currently working on a new publication of his poetry.

Pivovarov is convinced that since he was a child he has always been protected by higher powers, who, having discovered his talent, gave him an education, and in the early 1980s, when it became dangerous for him to live in the USSR, presented him with the opportunity to move to Czechoslovakia, where he did not have to adhere so strictly to the canon of socialist realism. They also blessed his happy marriage with Czech art historian Milena Slavická, who supported him during his most difficult years, when communist censorship did not allow exhibitions of conceptual artists. The only thing that these heavenly patrons demand is: “Work and more work you scumbag!” As for the muses, what do they look like? They can be a hybrid creature with the head and tail of a dog, or even a casket which stores darkness, or a house where a giant ear has grown on the facade. All this is material for paintings-poems. “A poet is an aristocrat of the spirit, and poetry is one of the highest forms of human spiritual self-expression,” explains Viktor Pivovarov.