Erik Bulatov. The Louvre. Gioconda, 1997-1998. Courtesy of the artist

Picture Postcard Bulatov in Nizhny Novgorod

‘Horizon’, an exhibition marking the 90th birthday of Erik Bulatov, one of Russia’s greatest living artists, consists of work assembled from ten private collections.

Erik Bulatov, who has spent his entire creative life exploring the possibilities of depicting space and light, has unwittingly staged an optical trick here: this exhibition is not so much about his own creative vision as about how his admirers and buyers see it.

The voice of Gleb Nikitin, governor of the Nizhny Novgorod Region, booms over the noise at the opening of Erik Bulatov's (b. 1933) solo show in a historical former warehouse, recently converted into an exhibition space. Microphones are set up opposite the entrance to the hall, partitioned off by walls with paintings. The sound first turns into a kind of noise mush, and no microphones or loudspeakers allow it to break through the partitions. But the governor's roar finally cuts through and silence prevails for a moment. Marina Loshak, curator of the exhibition and former director of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, calls Natalia Bulatova, the wife of the artist, on WhatsApp in Paris. Her girlish voice welcomes the guests at the opening. Then Erik joins in. His speech, much quieter, and detached. Almost nothing can be heard.

But the Nizhny Novgorod-Paris connection is important. "I opened Erik Bulatov's anniversary exhibition ‘Horizon’ in the warehouse! Eric Bulatov is one of the greatest living Russian artists, a classic of world painting," Governor Nikitin proudly posted during the opening event in his Telegram channel.

Erik Bulatov's exhibition in Nizhny Novgorod has turned out to be the main artistic and social event of the autumn season. If because of cancelled cultural exchange Russia’s leading national museums were unable to organise an exhibition of Erik Bulatov or to bring works from museums and private collections from abroad, here private collectors were able to unite and jointly organise an exhibition in honour of the artist's 90th birthday.

Collectors, art dealers and museum staff from both capitals came to the opening. Collectors Natalia Opaleva, Igor Markin, Sergei Limonov, Denis Khimilyayne, Dmitry Volodin, Irina and Anatoly Sedykh, Kristina Krasnyanskaya, Sarah Vinnitz. Vladimir Ovcharenko, art dealer and owner of Vladey auction house, wore a shirt from Gosha Rubchinskiy's 2018 collection, created for Bulatov's 85th birthday, brandishing the words ДРУГ ВРАГ (Friend Enemy), and posed for the cameras, unzipping his jacket. Gallery owners Sergei and Olga Popova ran tirelessly through the crowd, and even promised to sing karaoke the next night after the opening.

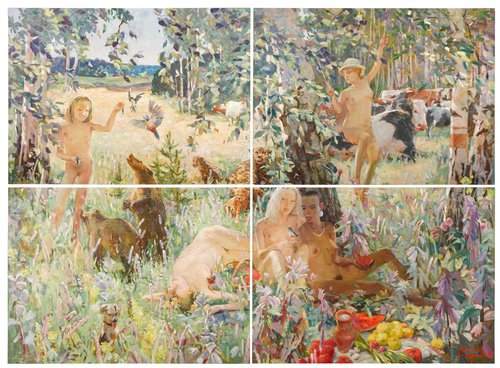

Bulatov's name was the magnet that drew all these people together in Nizhny Novgorod. Depicting typical characters in everyday circumstances – Soviet people against the background of Central Russian landscapes, urban landscapes and visual propaganda of his time – Bulatov, like Russian writers of the 19th century, created a broad panorama of the socialist period of the second half of the 20th century. And he broadened his horizons, went to the USA, to Spain, to France, to Italy. And then settled down between the fifth arrondissement of Paris, Moscow's Pokrovka Street and the centre of Florence. And all this is literally in his works, which are shown at the exhibition ‘Horizon’.

All eighteen large-scale paintings from ‘The Artist on the Plane’ 1967-1968 to ‘Autumn. Boulevard Sevastopol’ 2009–2010, were lent to the exhibition by ten Russian collectors. Among those whose names are on the labels are Shalva Breus, Vladimir Nekrasov, Ekaterina and Vladimir Semenikhin, Tamaz and Iveta Manasherov, Petr Aven and Igor Markin.

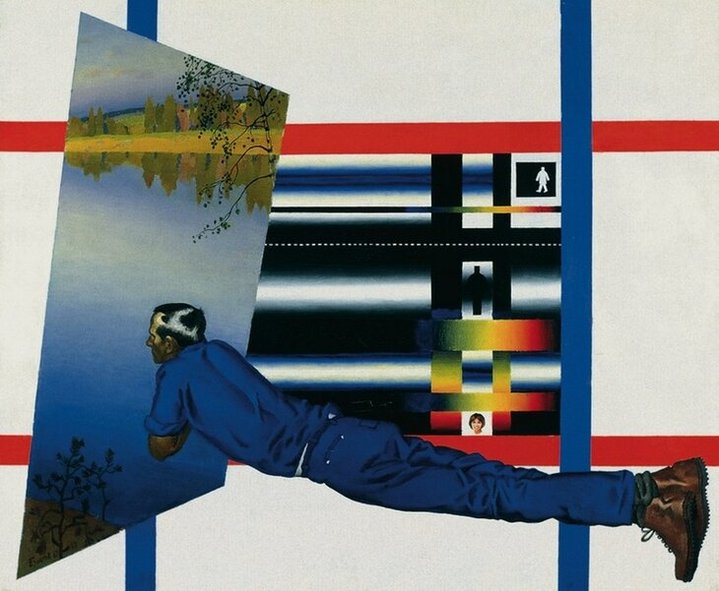

The works are grouped in pairs like photos from a pocket photo album. Scaling up the idea of the album, architect Yuri Avvakumov built identical walls inside the hall, dividing the space into ten sections and inside each one the paintings were hung opposite one another. Thus, deprived of perspective and thus the possibility for the viewer to ‘enter the picture’, to transcend the boundaries of the image which Bulatov cares so much about, here his paintings resemble a set of faded, flat, whitish postcards. The artist's favourite line "I live and see" is from Vsevolod Nekrasov's poem, but perhaps more apt here would be a quote from Mayakovsky, "About Time and Myself". Pairs of paintings are put together based on the internal life and external experiences of the artist. Here, in a work called ‘Artist on a Plane’, Bulatov's friend and collaborator Oleg Vassiliev (1931-2013) is suspended in space on a white background, studying a plane with a naturalistic depiction of a landscape, with the rest of the surface a deconstructed landscape, transformed into a blue and red grid with black and white light and shades. Displayed opposite is a work from 1973, where an unremarkable landscape depicting a rainy summer’s day in the suburbs of Moscow is dissected by a dotted line and the word in diminishing size: ‘Beware’.

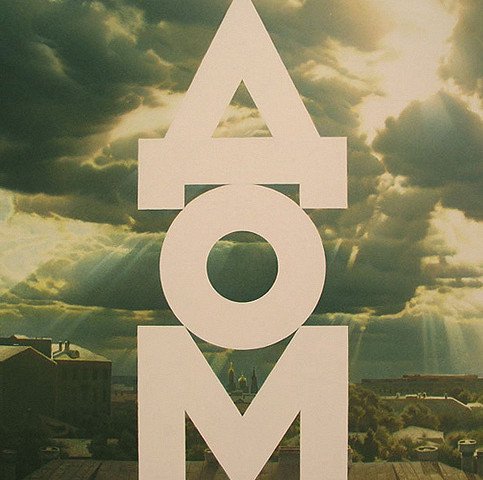

Here is ‘American Dream’ from 1992. The letters on the left and right form a visual corridor that pulls the viewer inside, to a place where a homeless man, covered with a newspaper, sleeps on the steps, and above him, like a Madonna in the altar, is a diva in red Playboy lingerie. And painted in the same year, opposite is a view of Moscow from the windows of a workshop on Pokrovka Street, illuminated by rays of the sun breaking through the clouds and covered vertically like shutters by the giant letters ДОМ ‘Home’.

Then there is ‘The Wanderer’, a painting on which the artist worked from 1993 to 2003. A man in wellington boots, with a stick in his hand is walking through an autumn thaw. There mud has turned into sludge, there are slushy puddles on the road. And above him, growing larger and larger like a Buddhist halo, is the emblem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russia’s name in the Soviet Union). Opposite hangs, ‘Autumn. Boulevard Sevastopol’. Puddles, cafe chairs in the rain. A soaked awning. A bus stop. Leaves on the pavement. Suddenly here you have the sense that the artist, who all his life depicted the everyday life of this large Soviet country without any hint of condemnation or moral judgement, suddenly turned into a singer of quiet personal happiness and into a master of Biedermeier.

But neither the artist himself nor the curator and architect of the exhibition allow us to believe it. Five small, early works by Bulatov are hung opposite the folding box of walls built by Avvakumov. These are pencil drawings of diagonals on paper, made in 1964. It was a process of searching for himself in art, when Bulatov, in his own words, was squeezing himself between Robert Falk (1886–1958) and Vladimir Favorsky (1886–1964). Then comes the oil on canvas ‘Cut’ from 1966, and, painted in the same year ‘Street’ with lights shining out from a dark space. This is the moment when space and light became the main subject of Erik Bulatov's art. You see this again in the works he has been making in recent years, devoid of everyday subjects, centred on white and black spatial constructions. But these latest works are not at the exhibition. There is a long queue of collectors for Bulatov's paintings, an artist who can work on one canvas for decades.

Horizon. To the 90th anniversary of Erik Bulatov

Nizhny Novgorod State Art Museum, Exhibition Warehouse

Nizhny Novgorod, Russia

11 November, 2023 – 21 January, 2024