Other Shores: winner of the Art Newspaper Russia Book Award

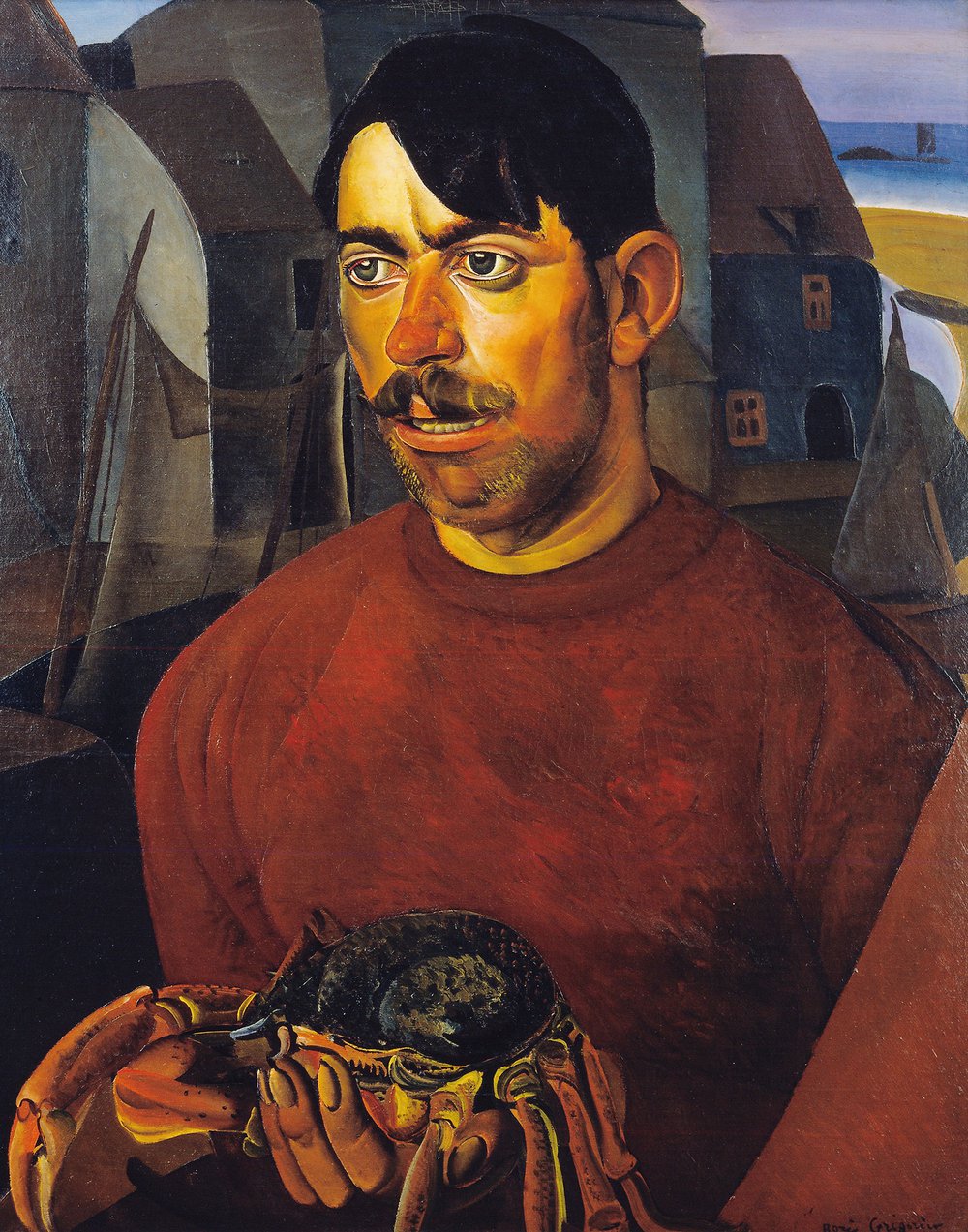

Boris Grigoriev. Fisherman with a Crab (Breton Fisherman), 1922–1923. Oil on canvas. Collection of Anatoly and Maya Beckerman, New York

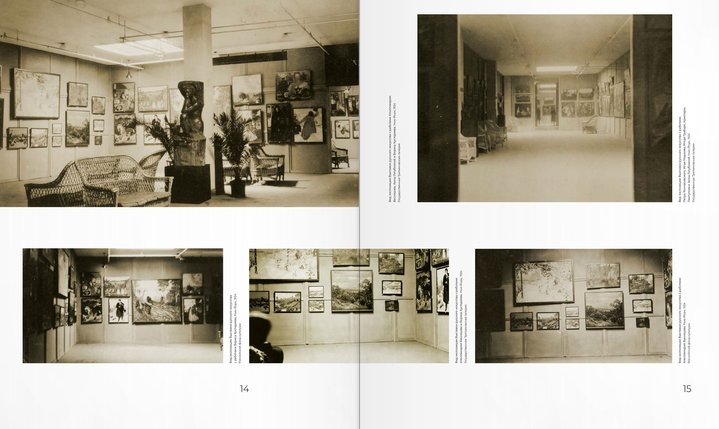

A recently published catalogue, ‘Other Shores’, to accompany the reconstructed American 1924 ‘Russian Art Exhibition’ at the Museum of Impressionism in Moscow has just won the prestigeous Russian Art Newspaper book of the year award.

‘Bourgeois art it is not’, said painter Igor Grabar when he returned to Moscow. He was referring to the Russian Art Exhibition in New York he had co-organised, which he was promoting as a success back at home. With hindsight, though, this comment seems questionable, it was not quite the proletarian art he claimed it to be. In 1924 this was really the swan song of a figurative aesthetic which had already lost its compass both in Russia and across Western Europe, giving way to the radical avant-garde which in turn paved the way to our contemporary world. For at this time the avant-garde was still aligned with revolutionary ideas in Russia and championing the proletariat (although this was rapidly changing, in the manner of a volte-face, the avant-garde was deemed ‘bourgeois’ by the 1930s, probably Grabar’s comments reflected the seeds of this change).

Back in the early 1920s, Americans had at first opened their hearts to Russians fleeing the bloody Revolution and civil war, and many artists had settled there, most notably Boris Anisfeld (1878-1973), David Burliuk (1882-1967), and Boris Grigoriev (1886-1939). It was not so much their art, however, but the exotic flavour of popular Slav émigré culture that appealed to the wider cultured American public. They loved the quaint decorativeness of Russian folk art, the bright colours and echos of Diaghilev’s fashionable Ballets Russes.

In the 1924 ‘Exhibition of Russian Art’ everything was for sale. Wealthy American collectors understood the point was to reach into their pockets to help, because after the revolution artists had suddenly found themselves with no patrons, and there was no market. But charity does not make up for the lack of a real market, something perhaps the organisers had not taken fully into account. And the brief time of openness and sympathy for Russians was not to last because in the mid 1920s, after Lenin’s death, things were quickly changing in Russia, and politically the Americans were still reluctant to acknowledge the status of the new Soviet Union of Socialist Republics, which did not happen until 1933. By then the US was plunged into Depression and the cold war had began.

So teetering on the brink of all this, despite being the most ambitious show of Russian art ever held in America, this exhibition project perhaps predictably washed up on the ‘other shore’. It was not as successful as the organisers had hoped and they sold a meagre 10% of the 1,000 works on view. By any standards, this is poor. But its failure as a commercial venture was only part of it, even visitor numbers were low despite glowing reports in the press at the time. The art on show was only proletarian in so far as it was easy to understand and figurative, but to the eyes of Russia’s great avant-garde artists, it was bourgeois and irrelevant. And the American public voted with their feet and their pockets, showing it was not needed there either. It was a post-script to a bygone era.

If the Russian Art Exhibition was a failed enterprise in 1924, it did not fare well in art history either as, until now, it has remained obscure and little referenced anywhere other than auction house catalogues where from time to time paintings with the familiar exhibition label on the reverse have come up for sale and where the fabled provenance has ironically always been considered a boon. In the West, exhibitions of Russia’s radical left art, fared much better. ‘The First Russian Art Exhibition’ in Berlin the Von Diemen Gallery in 1922, for example, has become part of the fabric of the story of Western European Modernism.

There is some consolation though. Its return, a century later in vastly edited form at Moscow’s Museum of Impressionism, can be considered a backdated slice of success. The museum’s own ethos was the perfect venue for figurative paintings with a beautiful aesthetic, somewhere close in spirit to impressionist art and particularly cherished in Russia today, not only among Russia’s greatest private art collectors. The museum’s dedicated team undertook painstaking original research, pulling it all together, to give fascinating insights into both the exhibition and its socio-political context. In the accompanying catalogue there are original essays by Russian curator Olga Yurkina, and American academics John Bowlt, and Edward Kasinec. There were many challenges in tracking down paintings a century later based on the scant and often inaccurate information in the original catalogue. And the difficulties in transporting paintings from American and Western European collections to Moscow for the show means that the catalogue for ‘Other Shores’ gives us a fuller picture of the 1924 show than the reconstructed exhibition itself. It is a glorious effort of bi-cultural co-operation, rigorous scholarship and bears a treasure trove of illustrations of paintings not often included in more staple Russian art publications. And although the original 1924 exhibition did not achieve the aims of its organisers, it was unquestionably an impressive undertaking and this catalogue – sadly for the moment only available in Russian - is a worthy addition to the shelves of anyone who is interested in Russian art both on a professional and amateur level.