Moshchitsky Brings Parajanov onto the Stage

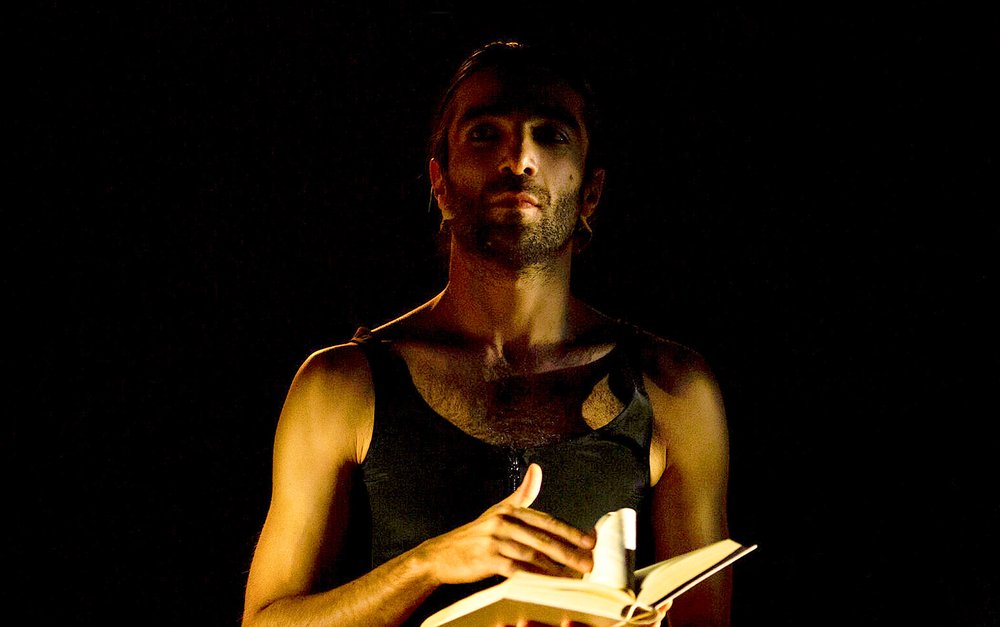

Moranal. Directed by Ilya Moshchitsky. Photo by Aleksandr Grebeshkov. Courtesy of Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art

In his production of ‘Moranal’ at VOICES 2024 in Berlin millennial theatre director Ilya Moshchitsky translates Sergei Parajanov’s collages into the language of the theatre. Critic Anton Khitrov explores what this work can tell us about the culture of the Soviet intelligentsia.

Armenian director of Russian origin Ilya Moshchitsky (b. 1984), one of the most interesting theatre experimenters of his generation, and his troupe Chronotope have staged a production of ‘Moranal’ in Berlin at VOICES 2024, as a tribute to Sergei Parajanov (1924–1990), who would have turned one hundred this year. A compilation of disparate texts, from Armenian poetry to Peter Brook they are united by an image from Parajanov’s film.

One of the most memorable images in ‘The Colour of Pomegrantes’ a film for which Soviet-Armenian director Sergei Parajanovbecame famous, is of a child lying on the roof of a church, surrounded by books which have been laid out to dry. The wind turns their pages. Last year, a few months before the centennial of the birth of this legendary director, the Chronotope Theater Association under the leadership of Ilya Moshchitsky, staged the play ‘Moranal’ in Yerevan. The title means ‘To Forget’ in Armenian, and Parajanov’s powerful image of the child with books on the roof is central to the play.

Near the beginning of the play the four Armenian-speaking actors: Andranik Mikaelyan, Zhanna Velitsyan, Maria Seyranyan and Aelita Gevorkyan slowly bring one book after another onto the stage and and open them. It lasts for ten minutes, by theatrical standards, an exceptionally long time. Only when the whole stage is covered with books do the actors begin to speak – in quotation marks. They are, of course, speaking in quotes from their books.

The text of ‘Moranal’ is pieced together from many sources: poetry by Armenian poets Nahapet Kuchak and Vahan Teryan, Milan Kundera’s novel ‘The Unbearable Lightness of Being’, ‘Three Sisters’ by Anton Chekhov, William Shakespeare’s ‘Macbeth’, and even childhood memories of the actors themselves. The quotations echo amongst themselves: some argue, others rhyme. Director Moshchitsky chose fragments that deal with the most essential issues of human life: memory, death, disappointment and hope.

Although Ilya Moshchitsky is originally from Russia, he has done a lot of work in Ukraine. The experimental theatre association Chronotope was conceived as a Russian company, it toured the Ukraine and was also resident in one of the most progressive theatre institutions in Moscow, the Vsevolod Meyerhold Centre. At the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Meyerhold Centre was shuttered due to the anti-war stance of its leaders. Chronotope moved to Armenia, where it is still based today. It has Armenian actors, and now they also produce plays in the Armenian language.

As well as referencing ‘The Colour of Pomegranates’ and Parajanov’s unrealized autobiographical screenplay ‘Confession’, Moshchitsky uses his collages not as direct quotes, but as models. Since the Soviet government prohibited Parajanov from makingfilms, he turned to these collages which he created using a technique completely uncharacteristic of Soviet visual art. There are figures cut from reproductions of classical paintings combined with things found at flea markets, patterned fabrics, and dried plants.

In a nice parallel, Moshchitsky has carefully assembled ‘Moranal’ like a collage with ready-made elements – fragments fromdifferent texts - combined together to make something new. In places the visual aesthetics of the performance evoke Parajanov's works, with their naive taste for luxury and for everything that might be considered beautiful, like flowers and pearls. In ‘Moranal’ there is much that might seem excessive, pretentious and archaic like video projections on a transparent curtain, or theeffeminate images of the actors, or the lavishly designed dresses in the finale. Yet all of this is a deliberate homage to Parajanov. And, it is his collages, not his cinematic work that lies at the heart of this production.

I interviewed Moshchitsky in January of 2022 a month before the Russian-Ukrainian war began and he revealed to me his deep love of reading and literature and that as a child he read prolifically, referring to himself a “bookworm”. Books are central to one’sidentity as a member of the Soviet intelligentsia, and also today for the contemporary Russian intelligentsia, though perhaps to a lesser extent.

With the outbreak of the full-scale war, disputes over Russian classical literature have assumed an increasingly important place in public discussion despite far more pressing issues than the influence of Pushkin or Dostoevsky on the nation's political traditions. The question of the guilt of Russian literature is something many are asking themselves now, or more bluntly, why were the books of the Russian intelligentsia impotent in the face of the tragedy that is unfolding today as a result of Russia's guilt. Looking at ‘Moranal’ in this context, I believe that Moshchitsky is not simply quoting the image of the library on the roof from ‘The Colour of Pomegranates’, it is not a question of form or structure, but something more fundamental relating to an idea behind the image. For Parajanov the boy lying on the roof among books laid out to dry is a metaphor for growing up through culture. To become the great Armenian poet Sayat-Nova, the hero must first absorb the knowledge and experience of previous generations. In Moshchitsky's works, books serve to disorient rather than help the characters.

One of the central questions in his play is whether culture can make you better, more worthy, more human. Among the literary sources used in Moranal are, on the one hand, Joseph Brodsky's Nobel speech, in which the poet asserts that literature ennobles society, and, on the other hand, an interview by legendary British theater director Peter Brook with Russian film critic Anton Dolin for Vedomosti newspaper, in which he insists on exactly the opposite: neither art nor education can turn people away from evil, and the history of the 20th century has proved this quite convincingly.

The theme of reading has another aspect that is also fundamental to understanding the lifestyle of the Soviet intelligentsia: books give hope that there is something else in the world besides the daily routine. The attempt to find meaning and beauty in a dull and prosaic reality is one of the main motifs in ‘Moranal’. Towards the end of the play, the audience watches a short video filmed in the village of Bjni, 30 kilometers from Yerevan. A visit to this village is described in Parajanov’s unrealized script ‘Confession’.Together with the cameraman, we walk along the poor, nondescript streets of Bjni, which lead us to a magnificent 11th century church. The subtitles of the video include a fragment from Parajanov's script: the story by the director of meeting the priest who served in this church, his family, and fellow villagers. Parajanov observes the rather ordinary everyday life of these people, observations that lead him to mystical experiences.

In this mini-movie that concludes Moshchitsky’s play, religious architecture functions as a kind of analog to the book: the presence of the medieval church gives meaning to everything around it. If the play questions the creative role of culture, it ends with the hope that culture can still help us.

It is an exceptionally clever work and yet has its flaws as a piece of theatre drama. In his best productions, Moshchitsky sets up a theatrical situation that is often exceptionally interesting to explore and experience in the auditorium. In ‘Michael Craig-Martin’s Oak’, the director (who also doubles as an actor) invites one of the members of the audience onstage to become his partner in the performance. Throughout the performance, the audience tries to understand who is in control of what is happening. Moshchitsky invites us to take part in an experiment that would bring us closer to answering the question of the distribution of power between the artist and his audience.

There is no such thing in ‘Moranal’ which is somehow closer to literature than theatre. The actors take turns to deliver their linesand this is really all that happens on the stage. The only way to understand the sources of the text is to watch a video of the performance that is freely available on YouTube, pausing it from time to time to look up this or that quote on the Internet. In the auditorium, you cannot help but feel that you are missing something important, that you cannot fully get to the bottom of the director's intentions.

It is reading without notes, and if Moshchitsky’s performance resembles a library, then it is one in which the covers of all the books have been torn off. It is difficult to say what kind of theatrical experience we are supposed to get in the end. While Sergei Parajanov made films that are still perceived today as an extremely convincing argument in favor of cinema as an independent and unique art form, Moshchitsky, contrary to his usual practice, offers us a performance that might be better seen as a book.