Mikhailov’s Surreal Early Photographs on View in Paris

Boris Mikhailov. Reverse Perspective. Exhibition view. Paris, 2025. Photo by Rebecca Fanuele. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve, Paris

Boris Mikhailov pioneered Soviet underground photography through innovative collage techniques and a disillusioned, yet philosophical outlook on a society plagued by doublethink and oppression. His early works from the 1960s and 1970s are now featured in ‘Reverse Perspective’ at the Suzanne Tarasieve Gallery in Paris. Somehow they look disturbingly topical today.

Born in Kharkiv and based today in Berlin, Boris Mikhailov (b. 1938) is an icon of Soviet underground photography. He has won many prestigious awards and is the only living artist from the former Soviet Union to have had a solo exhibition at New York’s MoMA. He began his career as an electromechanical engineer, experimenting with documentary film and photography in the 1960s. It was then, after tossing a bunch of films onto his bed, that he discovered what became his signature method of superimposing one diapositive film over another. As opposed to double exposure, this technique allowed him to achieve the same results faster and more easily. Fascinated by the complexity and dreamlike poetic ambiguity of the resulting images, Mikhailov created around 300 slides using this method. He called this series ‘Yesterday Sandwich’. In the early 1970s, he exhibited them at Kharkiv's amateur photography clubs accompanied by the music of Pink Floyd.

Today’s art critics view the series as a subtle criticism of Soviet society and its pervasive doublethink. Many people in the USSR lived double lives, outwardly conforming to Communist ideology while inwardly hating, despising or trying to ignore it. Against the backdrop of Brezhnev’s stagnation, Mikhailov’s choice of soundtrack was a bold anti-regime statement in itself, as Pink Floyd albums were not legally sold in the USSR and could only be obtained on the black market. Large, mural-like prints from this early series of slides open the ‘Reverse Perspective’ exhibition at the Suzanne Tarasieve gallery in the heart of the Marais district. You can see a few of these prints from the street through the window, and they immediately arrest you with their eerie, almost exaggerated topicality. They appear to be inspired by recent news, depicting a company of soldiers in black gas masks with enormous, shining angelic figures looming in the background. The contrast between the sublime beauty of spirituality and the ugliness of war is striking – yet the fact that the image is over half a century old is even more shocking.

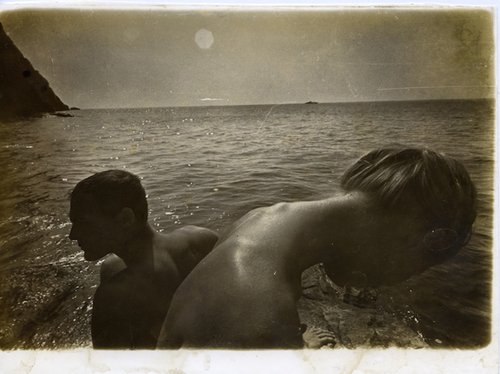

“My differences with the Soviet system are purely aesthetic,” – wrote the dissident writer and political émigré Andrei Sinyavsky, who served a six-year sentence in a penal colony, with a certain dark irony. This maxim could be applied to Mikhailov, too. Although he was not imprisoned for his views, he was fired from his factory job after someone discovered nude photographs in his laboratory. One of the “sandwiches”, now on display at ‘Reverse Perspectives’, also features a nude, and as I look at it, I experience a strange mixture of emotions — a schizoid split in personality worthy of another Mikhailovian ‘sandwich’. As someone who often visits contemporary art exhibitions in Europe and America, I am surprised that pictures of nudes which were not even displayed in the public domain could cost someone their job. Yet, as a person living in contemporary Russia, I am almost shocked that an image of a naked female body can be displayed like this: openly and uncensored in a public space.

In the current digital age, these images have a mesmerisingly real quality that is almost palpable. Similar effects can be achieved using Photoshop nowadays, yet they lack the spontaneity and undeniable materiality of Mikhailov’s handmade photo collages.

This exhibition brings together works from four different series from the 1960s and 1970s, including two complete sets of originals: Colour Backgrounds and Dvoyki (Pairs). It shows how an artist, unable to escape Soviet reality, distanced himself from its ugliness and hypocrisy through formal means. In Colour Backgrounds, he glues his black-and-white portraits of tired, miserable-looking fellow citizens onto sheets of brightly coloured cardboard. In Dvoyki, he creates pairs of almost identical snapshots, sometimes adding a touch of colour to the images manually. In doing so, he transcends mere social critique or reporting, transforming his photographs into conceptual objects. His approach is similar to that of the Moscow Conceptualists, artists who chose to live in “inner emigration”, willingly dissociating themselves from the Soviet reality that surrounded them. (In the 1970s, Mikhailov developed close creative ties with Ilya Kabakov (1933–2023) and his circle). Paradoxically, it was after the collapse of the Soviet Union that Mikhailov’s art became overtly socially critical. In the 1990s, he created ‘History of Illness’, a series of photographic portraits of marginalised people from his hometown. Among them were the homeless, drunkards and drug addicts – those who could not fit into the nascent capitalist society of independent Ukraine.

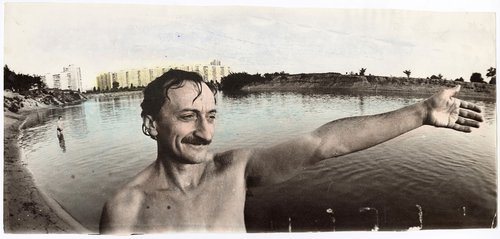

Due to their conceptual nature, Mikhailov’s early works have aged surprisingly well in the era of the digital devaluation of images. Nowadays, an image alone is not enough; installation has become the primary artistic medium, and Mikhailov’s exhibition follows this trend. In ‘Reverse Perspective’, each of the two complete series of originals is displayed as a single artwork: ‘Colour Backgrounds’ is combined on one wall, while ‘Dvoyki’ occupies three walls, surrounding viewers and transporting them to an imaginary space from which there is no escape. The exhibition’s grand finale is an enlarged print of a negative from the 1970s – Mikhailov’s self-portrait from the ‘Diary’ series. This series comprises unsorted photos from his personal archive spanning six decades from the 1960s to 2019. It shows a man stepping off the edge. This is another topical metaphor for a time when balance and reason appear to have been lost forever and art seems to be the only way to retain sanity.

Boris Mikhailov. Reverse Perspective

Paris, France

8 November 2025 – 17 January 2026