Love and Institutions: An Exhibition about Artist Couples in Almaty

Union of Artists. Exhibition view. Almaty, 2026. Photo by Roman Sazonov / Atelier Cauchema. Courtesy of Tselinny Centre for Contemporary Culture

Almaty’s newly opened Tselinny Centre for Contemporary Culture presents ‘Union of Artists’, an exhibition exploring thirteen artist couples from Central Asia. Beyond romance, the show reveals how creative partnerships sustained contemporary art across decades of institutional neglect in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan.

‘Union of Artists’ the title of a new exhibition at the Tselinny Centre of Contemporary Culture in Almaty is a conceptual pun which has nothing to do with conservative state-run artist associations. This union is the one made in heaven – a romantic one. The exhibition brings together thirteen married couples of artists from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. Although at first glance, the idea seems fun but a little superficial it quickly becomes clear that the theme of romantic–creative partnerships carries a deeper meaning.

This meaning emerges from the trajectory of contemporary art in Central Asia from the 1990s through the 2010s, as well as from the profound cultural shifts that took place in Almaty last year. Last autumn, two ambitious international art institutions opened in Kazakhstan’s largest city: the Almaty Museum of Arts and Tselinny. Union of Artists can be read as a direct response to this moment—an act of institutional self-reflection framed as a “romantic collection.” The exhibition looks to the future with a measured optimism (whether justified or not), while surveying the past with an understandable sense of melancholy. Art Focus Now takes a closer look at the first major exhibition to occupy Tselinny’s main exhibition space.

Originally, Tselinny had planned to present a solo exhibition by the artist duo Galim Madanov (1958–2025) and his wife, Zauresh Terekbay (b. 1964). Following Madanov’s death in October last year, however, the institution was forced to rethink its programme. The resulting exhibition, dedicated to his memory, has taken on a broader and more striking scope. In Central Asia, many of the region’s most prominent artists are also partners in life and in practice – or, perhaps more accurately, became widely known precisely through their shared artistic trajectories as couples.

Alongside an installation by Galim Madanov and Zauresh Terekbay, the exhibition brings together works by several foundational figures of Kazakh and Central Asian contemporary art. These include the pioneer Sergey Maslov (1952–2002) and one of the country’s most internationally recognised artists, Almagul Menlibayeva (b. 1969), who were a couple in the 1990s; another key innovator of that decade, Rustam Khalfin (1949–2008), and his wife Lidia Blinova (1948–1996); the conceptualist tandem Elena Vorobyova and Viktor Vorobyov (both born in 1959); Saule Suleimenova(b. 1970) and Kuanysh Bazargaliyev (b. 1969); Soviet-era classics Yevgeny Sidorkin (1930–1982) and Gulfairus Ismailova (1929–2013); and finally, a much younger couple – already acclaimed Sayan Baigaliev (b. 1996) and the painter Zhenya Baigali (b. 1987).

Adding only a handful of further names would effectively transform the exhibition into a comprehensive survey of Kazakhstan’s contemporary art scene, pitched in the spirit of: look at what has been happening here since the post-Soviet period – and how little you may have noticed; now is the time to catch up. For an institution newly tasked with visibility and popularisation, this is not only an understandable strategy, but a calculated and defensible one.

In this sense, the breadth of media represented in ‘Union of Artists’ is itself an asset: painting in varying degrees of experimentalism, graphic art, sculpture, collage, photography, installation, video, felt panels, and documentation of body-based practices. Bringing such a heterogeneous range of works into a single exhibition is no small curatorial challenge. More demanding still is the task of situating works – many of them originally produced in near-domestic conditions or for intimate gallery settings – within the cavernous former cinema, with its soaring ceilings and monumental scale.

The exhibition’s spatial logic ultimately succeeds, though not without recourse to a carefully calibrated sense of organised chaos. A constellation of small booths punctuates the hall, while a painted “sun” at its centre sends out rays that visually link works by the same couple. Viewers who choose to follow these connections sequentially are required to move back and forth across the space – a deliberate rejection of linear progression. Any attempt at a conventional, linear layout would have produced either vast empty voids or an oppressive density of works. The curator, Vladislav Sludsky, has instead fragmented the space with considerable finesse, ensuring that the artworks never feel diminished by scale, while retaining a palpable sense of openness and air.

As the exhibition makes clear, partnerships between artist-couples can take markedly different forms. Saule Suleimenova and Kuanysh Bazargaliyev, for instance, almost never collaborate. The exhibition includes just two exceptions – ‘Zhanaozen’ (2013) and ‘Nurses’ (2008) – which only serve to underscore the divergence of their artistic languages. Suleimenova’s work is driven by emotional immediacy and a desire to engage the viewer affectively, while Bazargaliyev adopts a more analytical, often ironic stance. Yet despite these differences, both artists share a pronounced socio-cultural focus, responding to issues acutely relevant in contemporary Kazakhstan, and both pursue a careful balance between experimentation and traditional media

Elena Vorobyova and Viktor Vorobyov, by contrast, have operated as a single artistic organism for several decades. The works presented here – ‘Evolution–Revolution’ (1995) and ‘Self-Portrait in an Oriental Style’ (2017) – align seamlessly with the exhibition’s central premise. In their practice, everyday objects and situations are transformed into metaphors for global concerns, while the distinction between the “high” and the “low” is deliberately collapsed: meaning is generated not by hierarchy, but by consciousness and its capacity for expansion. The co-authors construct a self-contained micro-world in which artistic perception reshapes the everyday into a mode of being. At the same time, the exhibition also includes earlier solo works by Elena, subtly foregrounding the evolution from individual practice to a fully integrated collaborative voice.

Sayan Baigaliev also works with everyday environments, but for him autobiographical elements are more important, while the family world becomes a space of protection, support, and self-knowledge. In his new painterly sculpture ‘The Story of One Carpet’ which still smells of fresh paint, as well as in the painting ‘Rib to Rib’ by Zhenya Baigali, the family appears as an inseparable organism – as if a third living being. Despite differences in style, both artists remain committed to painting and seek ways to develop it within a contemporary context.

Alibai Bapanov and Saule Bapanova are united by a shared commitment to Turkic wool-working traditions. When they first turned to this material, it was largely perceived as belonging to the realm of decorative or applied art. By combining national ornament with lyrical abstraction, they revealed in both traditions a common impulse: an attempt to comprehend the relationship between the human and the cosmic. In doing so, they powerfully reactivated a historical technique within the language of contemporary art.

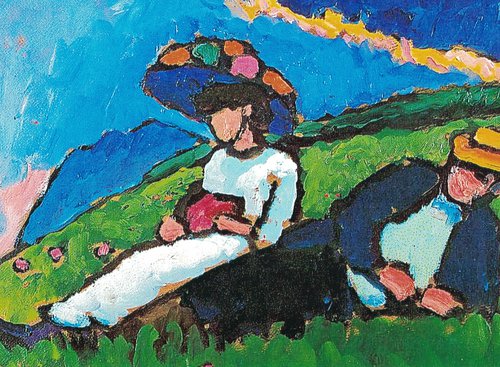

Cosmic themes also emerge in works by Sergey Maslov and Almagul Menlibayeva created during the period of their relationship. Maslov, already an established figure, initially acted as a mentor to the young Menlibayeva. Their romantic partnership thus intertwined pedagogy with the vitality of a new perspective – one that propelled Maslov toward a subsequent phase in his practice. Works from this period resonate strongly with one another: for Maslov, they rank among his most significant painterly achievements, while for Menlibayeva they function more as a prologue. She would later emerge on the international stage primarily as a leading figure in performance and video, reframing these early paintings as the point of departure for a markedly different, expanded practice.

Perhaps the most complex work in the exhibition is the installation ‘Transgression’ by Madanov and Terekbay. It is a collage composed of several hundred images referencing mass and high culture, everyday life, and personal experience. This fragmented and oversaturated reality can be associated with the world that opened up to Kazakhstan after the Iron Curtain came down. The sensation of both freedom and confusion it brought coexist within the installation.

In a similar way, from the late 1980s onward, the world of contemporary art began to open up to Kazakhstani artists. Yet only a few dared to immerse themselves in it, while for much of society, the state, and the elites it remained an alien and hostile territory. A slow shift in attitudes has become visible only in recent years. The emergence of Tselinny is one of the fortunate signs of this change.

For more than thirty years, however, contemporary art in Kazakhstan existed almost without institutional support. It survived and developed through the efforts of a handful of enthusiasts and attracted interest only from a narrow layer of intellectuals. A significant portion of artists’ energy was spent resisting the surrounding context. Some did not live to see the changes.

‘Union of Artists’ is, in this sense, an exhibition about a formative historical period – and about how contemporary art practitioners worked for years against the odds, patiently constructing an ecosystem for themselves where none existed. As the curator Vladislav Sludsky notes, artists’ families and circles of friends were compelled to compensate for the absence of cultural infrastructure, informally assuming functions traditionally performed by institutions such as the official Union of Artists. What initially presents itself as an “exhibition about love” thus reveals a deeper proposition: it is an exhibition about love as a productive force – one capable of sustaining practice, building communities, and effecting real change. Without it, there would quite simply be nothing to show today at Tselinny Centre of Contemporary Culture or at the Almaty Museum of Arts.

Union of Artists

Tselinny Centre for Contemporary Culture

Almaty, Kazakhstan

15 January – 19 April 2026