Light in New Jerusalem

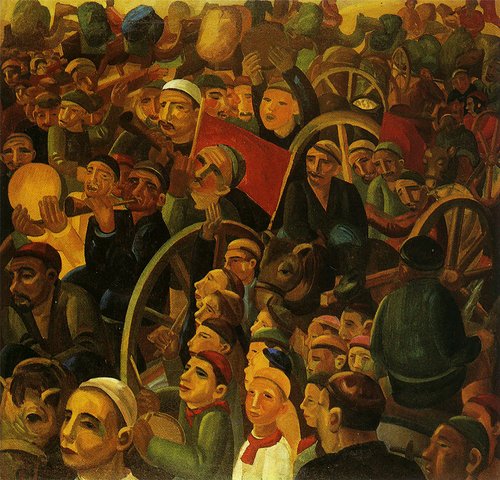

Alexander Volkov. To work. Morning in Shakhimardan, 1932. Courtesy of New Jerusalem State Museum of History and Art

An exhibition at the New Jerusalem Museum which combines two museum collections from Uzbekistan and Russia now on view in Istra, a small town in the outskirts of Moscow, creates an alternative history of Soviet Art.

The exhibition ‘Light Between Worlds’ is spread out over two floors of the new Russian artistic Mecca and includes more than 160 works by some forty artists from the collections of the I.V. Savitsky Museum in Nukus, Uzbekistan and the New Jerusalem Museum in Istra. It opens with a double-sided work by Alexander Volkov (1886–1957) from 1913–14: on one side ‘The Demon’ echoing Mikhail Vrubel (1856–1910) and on the other ‘The Face of Christ’ closest perhaps to the work of Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664). The exhibition also concludes with a religious theme: biblical paintings by Sergei Romanovich (1894–1968) and Lev Zhegin (1892–1969), and mystical drawings by Vasily Chekrygin (1897–1922). In this, one can see the clear intention of the curators: to show artists balancing between light and darkness, even if the light of glory and the darkness of oblivion.

It is difficult to avoid metaphors when writing about an exhibition in this new mega museum on the outskirts of Moscow. The proximity of the famous monastery, built by Patriarch Nikon in the 17th century as his residence, faithfully copying Jerusalem in its layout, sets the tone for religious associations, which are also present in the title ‘Light Between Worlds’. But when speaking about the Nukus Museum, wherever its collection is exhibited, symbolism is equally inevitable.

Nukus is the capital of Karakalpakstan. In the mid-1950s, when Igor Savitsky (1915–1984), the future founder of the museum, first arrived there, Nukus was a small town with a population of fewer than 39,000 people. Today more than 343,000 people live there, making it the fifth-largest city in Uzbekistan. And in this city is one of the world's finest collections of Soviet avant-garde art. A paradox that draws intellectuals – a museum amidst the sands.

Karakalpakstan is a sovereign republic within Uzbekistan. Although its area occupies 40 per cent of the country’s territory, it is squeezed between three deserts – the Karakum, Kyzylkum, and Aralkum (the former Aral Sea). In the years that passed from the founding of the museum in Nukus till today, one of the most terrible ecological catastrophes of the 20th century has taken place on this territory – the disappearance of an inland sea. In the 1950s it was amongst the top five endorheic bodies of water on the planet, and today it no longer exists, fundamentally changing the climate of the surrounding area. Even the colour of the sky above Nukus, as old artists say, has changed.

In 1989, an illustrated album ‘Avant-garde, Stopped in Its Tracks’ was published in Leningrad, dedicated to the museum in Nukus. Since then, for over three decades the catastrophe of the Aral Sea has evoked comparison with the fate of the Soviet avant-garde, which was a powerful artistic movement that completely disappeared, literally ground down by the era. The Turan tiger also disappeared without trace: the last one in Karakalpakstan was killed in 1947.

Igor Savitsky initially kept his entire collection in a garage. And when in 1966 it officially became the State Museum of Arts of the Karakalpak ASSR, its staff numbered one person – the director himself. The museum’s founder turned Nukus’s disadvantages into advantages. A small town? Here everyone knows each other. Here it’s possible to reach the highest authorities. And Savitsky both “extorted” and “begged for” funding for museum needs from the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Karakalpak ASSR, or from the First Secretary of the Karakalpak Regional Committee of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan, and other officials, using local acquaintances, connections and support. An autonomous republic? Here one could use the national pride of the Karakalpaks, and the hidden opposition between Nukus and Tashkent for the needs of the museum. A remote region? Here the ideological opposition between “formalism” and “socialist realism” was incomprehensible to anyone, because the Karakalpaks had no tradition of figurative art before the arrival of Soviet power (de facto Igor Savitsky was the founder of the school of landscape painting in Karakalpakstan), so both “avant-garde” and “realism” were perceived as “Russian painting”, and it was prestigious to own a collection of Russian art. What began as a private artistic initiative in the sixties became, in independent Uzbekistan after the collapse of the USSR, a national symbol and export commodity. Thus, the catalogue of the exhibition ‘Survivors in the Red Sands’ (Caen, 1998) opened with greetings from Jacques Chirac then President of the French Republic and Islam Karimov then President of the Republic of Uzbekistan – a pinnacle that is impossible to surpass.

In Karakalpakstan it proved possible to preserve the avant-garde in a state museum. And this connects the Nukus Museum with the New Jerusalem Museum. The ‘Moscow Regional Museum of Local History’ in the town of Istra (the historical name of the current New Jerusalem Museum) began collecting “Soviet painting and graphics” in 1977: but under this title lies hidden a unique selection of art from the 1920s–1930s and 1970s–1980s, in which an important place is occupied by the "Eastern collection", that is, works by Alexander Volkov and his sons Valery (1928–2020) and Alexander (b. 1937), as well as by Volkov’s pupil Evgeny Kravchenko (1937–2010). And the exhibition opens with the “Eastern collections” of both museums, which are built into a unified line of comparisons. These parallels continue throughout much of the exhibition space.

The comparison of the two collections is obvious. But this is the first exhibition devoted to it. Many artists would have been forgotten forever if not for Savitsky and his museum. But the same can be said about the New Jerusalem Museum. However, its collection is known only to specialists. And the exhibition draws attention to the way that the collection in the Moscow region has been unfairly undervalued. It is constructed like antiphonal singing in an Orthodox church, where one voice responds to another, but only together do they build a common harmony, and both parts are performed by the same choir.

The fate of many of the artists in this exhibition was unfortunate. Pavel Surikov (1897–1943) died of chronic tuberculosis. During the siege of Leningrad, Valentina Markova (1907–1941) left home one day and never returned. Lyudmila Bakulina (1905–1980) stopped painting after 1933.

For Savitsky it was a matter of honour to collect paintings by forgotten and repressed artists. In which it is difficult not to see a reflection of the history of his own clan. Igor Savitsky came from a high-ranking Soviet family that had been subjected to repression. His uncle Dmitry Florinsky was the founder and first head of the protocol department of the USSR People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs. In 1934 the ‘Florinsky Case’ became the first judicial process after the passage of a new resolution ‘On criminal responsibility for sodomy’. And Florinsky himself was shot after several years in the labour camps.

The first generation of the Russian avant-garde such as Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935), Vassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) and Marc Chagall 1887–1985) managed to make themselves heard loudly on international platforms during their lifetimes. The second generation was not so fortunate. Most of those who survived were forgotten even during their lifetimes, in their own country (now countries, after the collapse of the empire) – and the exhibition gives a vivid picture of what Soviet art could have been if these artists had not been pushed out of exhibition life in the thirties. There is Valentina Markova, a metaphysical painter in the style of de Chirico, or Nikolai Viting (1910–1991) an original expressionist and Lyudmila Bakulina a follower of Niko Pirosmani (1862–1918). The exhibition illuminates an alternative history of Soviet art of the 1920s and 1930s.

Light Between Worlds

New Jerusalem State Museum of History and Art

Istra, Moscow Region

30 May – 8 November 2025