Kyiv Biennial in Vienna and Beyond

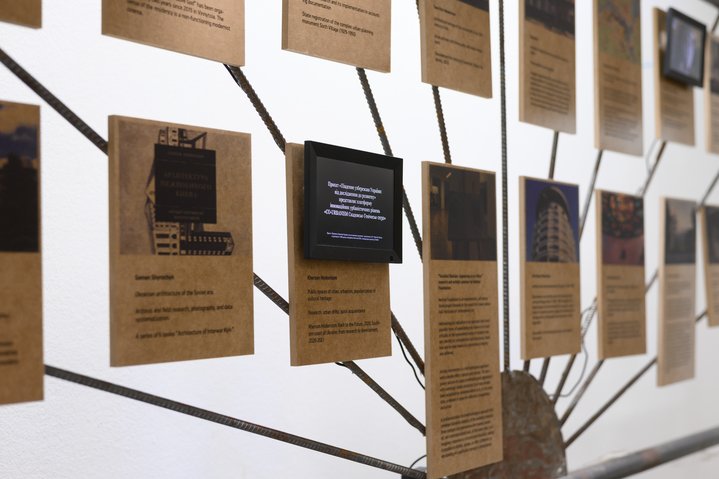

De Ne De. Exhibition view. Kyiv Biennial. Augarten Contemporary. Vienna, 2023. Photo by Joanna Pianka. Courtesy of Augarten Contemporary

The Kyiv Biennial is taking place in various cities throughout Central and Eastern Europe. The main exhibition in Vienna shows the power of solidarity and the horizontal ties between artists bonding across borders over the tragic situation in Ukraine.

This year, the Kyiv Biennial has no title nor is it located in any specific place; the circumstances speak for themselves. A curatorial statement reads, “The geopolitical rupture and dislocation that form the background to this biennial constitute the reality that connects its contents”. It is taking place across eight cities throughout Central and Eastern Europe including three in Ukraine: Kyiv, Ivano-Frankivsk and Uzhhorod; and in Berlin, Warsaw, Lublin, Antwerp and Vienna which is hosting the main exhibition. It is a dispersal reflecting the plight of the Ukrainian artistic community which is today divided and scattered throughout Europe. The biennial brings forth a sense of reintegration, however temporary.

Following the 2014 Maidan revolution in Ukraine which ushered in a wind of creative energy, the Kyiv Biennial was founded in 2015. But it was also the era which saw the annexation of Crimea and the beginning of the Donbas conflict, which boiled away for eight long years until the events of 2022. Organized by the Visual Culture Research Center, the Biennial was born in an environment fraught with problems and questions of sovereignty, nationalism, war, migration and soviet colonialism.

This latest, fifth edition was assembled in just four months, a feat of camaraderie, by virtue of the horizontal networks of Ukrainian artists and their European friends and colleagues. Numerous independent art spaces have offered their premises and organizations, such as transit.org have donated much needed funds. You can really feel this grassroots authenticity. It is, according to New York Times critic Jason Farago, the “Most Energizing Exhibition of the Year.” That from a country whose cultural capital has been ruthlessly attacked - there are over 1,373 damaged sites of cultural infrastructure; almost a third of them have been destroyed, including 69 museums and galleries. With many territories under occupation and subject to ongoing assaults, the figures are growing daily.

This tragic, cultural destruction is addressed by many artists in the main exhibition in Vienna. One of the most poignant is an installation by the Livyj Bereh organization, founded in 2022 by volunteers offering targeted assistance such as the restoration of damaged buildings and the supply of military units. The installation consists of fragments of destroyed homes which they have collected – bits of wood, bricks, broken pots. It could pass as the stuff of anthropological research if it were not from the households of living humans, and alongside the installation there is a video piece of an elderly woman standing alone in her home which has been razed to the ground. All you see is earth and rubble.

This close relationship between us humans and the land we inhabit, notions of ecology and possession, is explored deeper by Vitalii Atanasov in a video about the history of the Sasyk Lagoon, where Soviet intervention in an attempt to produce a freshwater reserve for irrigation, resulted in disaster. Paralleling the recent Kakhovka dam disaster, this raises questions today about how the ecological reality created during the USSR – one we have come to inherit – has shaped the Anthropocene.

The De Ne De collective have brought to Vienna a war damaged brutalist chandelier from a Soviet-era cinema in Dnipro and are building a nuanced investigation around of legacy of soviet architecture, where it can act as both a symbol of oppression and as a victim of it.

Against the background of trauma, it comes as some surprise that the works by Ukrainian artists are so exceptionally considered. Curators Serge Klymko, Hedwig Saxenhuber and Georg Schöllhammer also offer dialogues with works by European and international artists which brings wider perspectives to the themes and issues raised. Turner Prize winner and Venice Biennale participant Laure Prouvost (b. 1978) is showing a five-part video installation which he created before the full-scale invasion from 2010 to 2019. TV screens are either covered with a cloth or face the floor, deconstructing the medium, creating a sense of frustration and unease. Now with hindsight, in the current context, it can perhaps read as a critique of media’s own involvement in the conflict. Weak Signal IV by Wolfgang Tillmans (b. 1968), similarly playing on the media, is a huge printout of a television still, taken in a St. Petersburg hotel room in 2014. Tillmans also invited photographer Friedrich Bungert to display a series of photographic portraits of injured Ukrainians alongside his work.

While works by major European artists are scattered throughout the show chosen for their connections to the current issues - obliterated and obscured meanings, media interference, fractured communication – in this context they pale in comparison to lesser-known Ukrainian artists and European colleagues who are close to the conflict, their works full of sincerity, drama, and distress. Artists are constantly being pushed against a wall when it comes to addressing this world-threatening conflict. And many Ukrainian artists have literally gone to the frontline – just dare to compare that experience with the otherwise peaceful environment in which contemporary art in Europe is formed. They show the power of artistic networks which function as a support community, something like an organism adapting to disease, and through these networks and collaboration with selected institutions, media outlets, funding bodies, residencies and grassroots organizations, artists are searching for an antidote to the outbreak of totalitarianism and aggression.