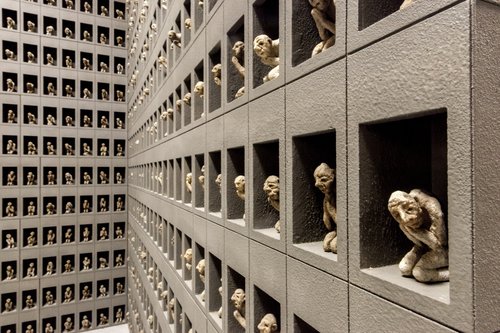

Andrey Kuzkin. Not Here. Exhibition view. Moscow, 2026. Photo by Evgeniya Senina. Courtesy of pop/off/art gallery

Kuzkin’s Quiet Comeback: Is There a Life after Exile?

After spending two and a half years in exile, sculptor and performance artist Andrey Kuzkin has unveiled a solo show at pop/off/art gallery in Moscow. The exhibition brings together works he has created abroad in the West. Continuing themes and projects started years ago, this show reflects on the tragic current events, while opening new paths in art.

According to various estimates, up to one million Russians have left their home country since 2022 for a variety of reasons. Some have been afraid of conscription into the army, some have faced persecution for their protest activities and others could no longer see any prospects for themselves or their children. This recent migration has brought people from all walks of life to new international shores, including IT specialists, civil activists, oligarchs, artists, and art curators. The art scenes in Moscow and St Petersburg have been affected the most drastically. Many talented emerging or reputable mid-career artists have fled abroad. However, there is an opposite trend that is often overlooked by statisticians. After the passage of time, some of these emigrants are returning to Russia. Andrei Kuzkin (b. 1979), for example, spent two and a half years in France, but never cut his ties with Russia. While he was away, a solo exhibition of his work at the prestigious Anna Nova gallery in St Petersburg attracted around 7,000 visitors – almost a record number for an independent gallery in Russia’s second capital city.

After spending over two years in France, Kuzkin decided to return to his hometown of Moscow. “In Russia, you can work, but you have to keep silent. Out there, you can say whatever you want, but nobody cares,” he once told me in a private conversation. He chose the pain of keeping silent over the frustration of being ignored. His most recent exhibition, organized jointly by the Anna Nova gallery in St. Petersburg and the pop/off/art gallery in Moscow, is called ‘Not Here’. The title can be taken quite literally, as it showcases artworks he has created while living abroad. Yet there is a deeper meaning. After all, an artist is always the quintessential outsider, a stranger everywhere. The main theme of the exhibition is escapism … and the ultimate impossibility of escape.

Kuzkin’s art has always been philosophical, grappling with the fundamental existential questions of the human condition: the body, suffering, and mortality. He has always been fascinated by the dichotomy of mortal human flesh being a ‘prison for the soul’, and the spirit confined within it. Even in exile, he remained true to himself. His artworks became smaller in scale as he had no studio in which to create large sculptures in Paris, and they became more introspective as his social circle shrank in an unfamiliar city abroad. They are displayed in the small, intimate space of the pop/off/art gallery in the centre of Moscow. Narrow and windowless with a vaulted brick ceiling, the space resembles a dungeon corridor. Curated by the artist himself, ‘Not Here’ seems to capture the current trend in Moscow for semi-underground, self-organised exhibitions in apartments, artists’ studios, and other unlikely places

The first part of the exhibition shows the evolution of projects that Kuzkin started long before his exile, when they were transplanted, sometimes quite literally, into Western European soil. The ‘Cards’ series originates from a performance called ‘1 4 12 3 18 9 16 1 – 15 8 99 3’, in which the artist asked other people to give him random small objects found in their pockets or handbags. He then glued these objects onto sheets of cardboard, wrote numbers in the corners, and gave the artworks back to the people who had given him the objects. These numbers held personal significance for Kuzkin; he had developed a secret numeric language that only he could understand. In France, the performance evolved into a kind of solitary meditation: no one else was involved, and the artist used objects he found in the streets of Paris, such as leaves, flowers, small toys, and lost keys.

These laconic pieces are placed along narrow shelves on the walls, while a textile curtain with a photographic print divides the long, narrow hallway into two. The photo on the curtain depicts a man standing on his head with his arms and legs in the air, his face buried in the ground on a hill above an idyllic European town. The man is Kuzkin himself, and his pose will be familiar to his fans in Russia. Conceived as an homage to his late father, the artist Alexander Kuzkin (1933–1983), it is based on his eponymous lithograph depicting an actual tree 99 times. Andrei Kuzkin poses in various locations, pretending to turn into a tree and become one with nature, even if only for a short time. “The idea here is escapism and retreating into some kind of parallel world,” says the artist about this part of the exhibition. “That is, the desire to become a plant or retreat into a semi-insane world of numbers.” The only thing that keeps him grounded in this section, he says, is the artwork that depicts a suffering human body, called ‘A Bread Boy in an Earthen Coat’.

Since 2008, Kuzkin has been creating sculptures from bread pulp. For him, bread is a multi-layered symbol of raw and suffering human flesh, rich with different connotations – from the concept of transubstantiation in Christian liturgy to the tradition of making bread figurines in Russian prisons. The sculptures have varied in size, ranging from the three-metre-tall ‘Heroes of Levitation’ to the hundreds of small figurines that make up his award-winning ‘Prayers and Heroes’ installation, which was exhibited at the Moscow Biennale and the Garage Triennale. Eventually, he grew tired of this medium and planned to say goodbye to it after a major exhibition of bread artworks, scheduled for autumn 2022 at the State Tretyakov Gallery. However, along with many other cultural initiatives, it was cancelled after the start of Russia’s armed conflict with Ukraine. In exile, Kuzkin continued to work with bread, and the second part of the exhibition shows how his relationship with his signature medium has evolved during this period. He started combining it with painting, and this unlikely union proved successful, as demonstrated by two artworks facing each other. The first, titled ‘Deliverance’, is a brightly coloured abstract painting in a heavy frame formed of tiny human figures that appear to be writhing in agony. Made out of salty bread pulp, they surround the canvas like an eerie, Dante-esque whirlwind of sinners. The second, titled ‘Art – Life in Paradise’, features a sculpted human face and two hands emerging from the surface of a semi-abstract jungle scene. This character, the artist’s alter ego, looks at the world beyond the canvas with quiet bewilderment, ready to dive back into the painted thicket. The theme of escape resurfaces here – quite literally. “These artworks are transitional,” Kuzkin told me when I asked if they marked the beginning of a new series. For him, they are a transition between his signature bread sculptures and whatever will come next – he seemed unsure as to exactly what that would be.

Yet the second part of the exhibition proves that Kuzkin has not exhausted the possibilities of using bread as a medium. Tucked discreetly on the shelves behind the gallery's reception counter are works that address current events more directly. While in exile, the artist began combining bread pulp with other materials. In a small piece from the ‘On the Ruins’ series, a human figure is placed atop debris – a tiny yet powerful monument that requires no explanation. In the ‘Cubes’ series, he combines bread pulp with soil. The cubes of human figures and earth are the same size and can be stacked on top of each other. “They are completely interchangeable,” the artist noted, rearranging the cubes in front of visitors on opening night. The metaphor becomes even more poignant when you learn that the soil comes from a cemetery where soldiers killed in the First World War were buried.

Kuzkin says he did not go there on purpose, but he obviously enjoys the incidental symbolism. “A man with a spade looks much less suspicious in a cemetery than in a park or on a boulevard,” he explains rather deadpan. “There was a cemetery near my home in Paris, so when I needed soil once, I went there. Of course, I didn’t dig the graves themselves; I dug somewhere near the fence.” In a topsy-turvy world of today, a world that stands on its head as firmly as Kuzkin himself during his physically demanding performances, metaphors can come alive and symbols can turn out to be more relevant than newspaper headlines. Whatever his reasons for coming back home, Kuzkin came prepared.