Justice for Morozovs

The groundbreaking collection by Ivan and Mikhail Morozov finally gets to Paris. Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris presents a second exhibition dedicated to prominent Russian art patrons

Two hundred masterpieces from the collection of Russian pioneering patrons of modern art Ivan (1871–1921) and Mikhail Morozov (1870–1903) will occupy the entire Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris until 22 February 2022. The whole collection, which miraculously survived both revolution and war, was divided among several museums and then partially kept in vaults for decades, left Russia the first time for what is its world premiere. Dedicated to key Russian philanthropists, ‘The Morozov collection. Icons of Modern Art’ is a no less dramatic sequel of ‘The Shchukin Collection’ exhibition that took place five years ago in the same venue.

The long-awaited opening of the exhibition had to be postponed twice, due to the pandemic. After protracted negotiations at the highest state levels and logistical challenges, the unprecedented tour of this huge national collection has already been called an institutional breakthrough and is a “diplomatic masterpiece”. The collective market value of these paintings is so high that it can barely be estimated. The greater part was provided by the Hermitage Museum, by the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts and by the Tretyakov Gallery. Major loans also came from the State Russian Museum, the National Art Museum of Belarus, the Dnipropetrovsk Art Museum (Ukraine), the private MAGMA collection Viatcheslav Moshe Kantor and the collections of Pyotr Aven and Vladimir and Ekaterina Semenikhin.

Passionate about art, the two Morozov brothers, young heirs of a textile empire, built their collections strictly on personal preferences. The exhibition, curated by Anne Baldassari, from the start brings visitors face to face with Russian artists and patrons. Through a plaster copy of Anna Golubkina’s (1864–1927) high relief, commissioned by Ivan and Mikhail’s relative Savva Morozov for the facade of the Moscow Art Theatre, we enter an exclusively Russian portrait gallery. Members of the Morozov family, collectors and philanthropists from their circle - Pavel Tretyakov, Sergey Shchukin and Savva Mamontov – seem to keep social distance on the walls. Indeed, in the elongated spacious room that opens the exhibition, each of the paintings by Valentin Serov (1865–1911), Konstantin Korovin (1861–1939), Ilya Repin (1844–1930), Mikhail Vrubel (1856–1910), Alexander Golovin (1863–1930) and Konstantin Makovsky (1839–1915) have a rare opportunity to breathe. The quiet grey colour of the exhibition space references the Morozov mansion and leaves room for reflection.

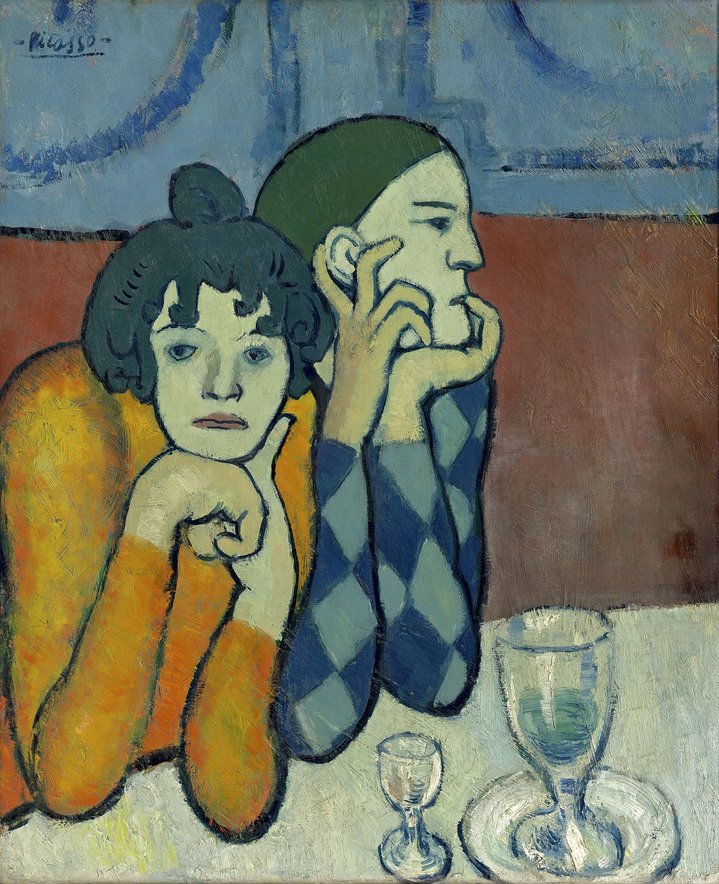

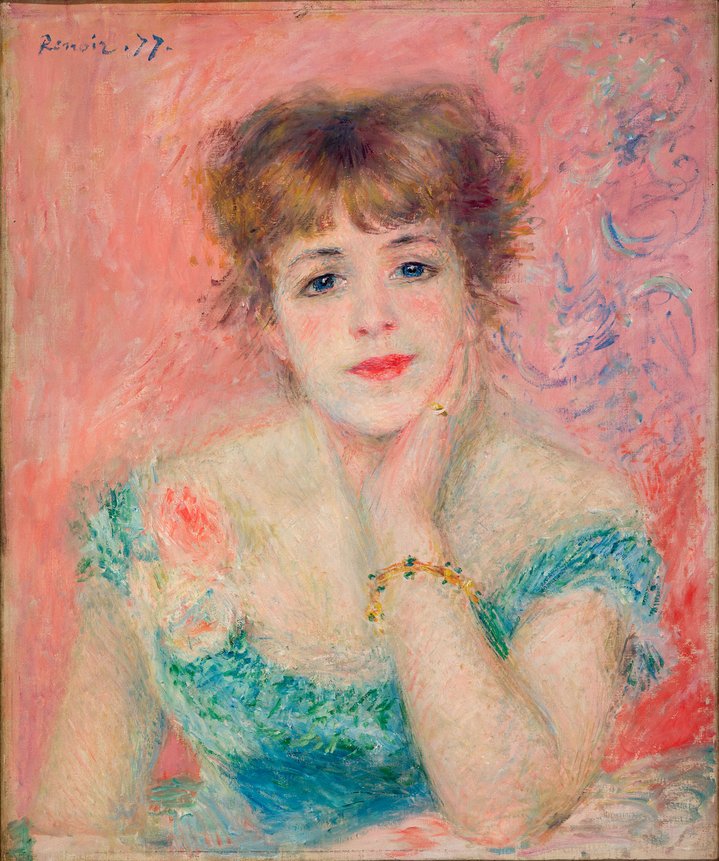

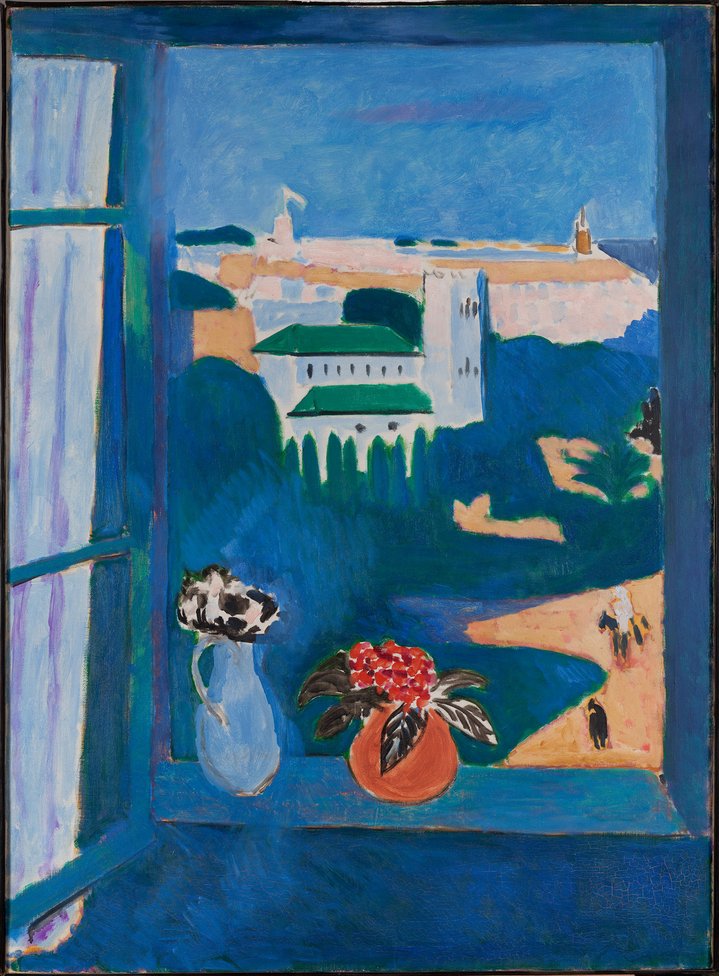

The next hall is devoted entirely to photographs of the paintings as they once hung in Ivan Morozov’s mansion. Using enlarged photos, Baldassari emphasizes the importance of the original hangings. The post-revolutionary shots recall the process of nationalization and evacuation of the collection during the Great Patriotic war. The most striking image here is a photo of the Morozovs’ dining room with Stalin’s portrait installed right in the middle. Only later, we get to the first hall of French paintings, vividly demonstrating the taste and visionary potential of the Morozovs, who in their twenties had already begun to collect Picasso, Manet, Cézanne, Toulouse-Lautrec and Renoir, not forgetting Korovin. The following room invites us right into the house of Ivan Morozov: we see a triptych and panels by Bonnard, specially commissioned for the entrance staircase. This is a vivid cycle, dedicated to the seasons and it is immediately captivating. Onward, we reach a suite of rooms divided according to either theme or artist: two halls with landscapes, personal rooms with works by Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse (with 11 paintings in each!), Sergei Konenkov (1874–1971) (three sculptures), and the Russian Cézannists, one small passing room with still-lifes and a gallery dedicated to the nudes depicted against all academic cliches of this period. The stunning Van Gogh’s ‘Prisoners Exercising’ last seen outside Russia at London’s Tate Britain, is the only piece placed in a separate space all to itself, reminding us that Ivan Morozov’s collection boasted at least four of his paintings. Two beams of light cut through the dark, well-shaped space of the room: one directed at the blank wall high above, the other at Van Gogh’s prisoners.

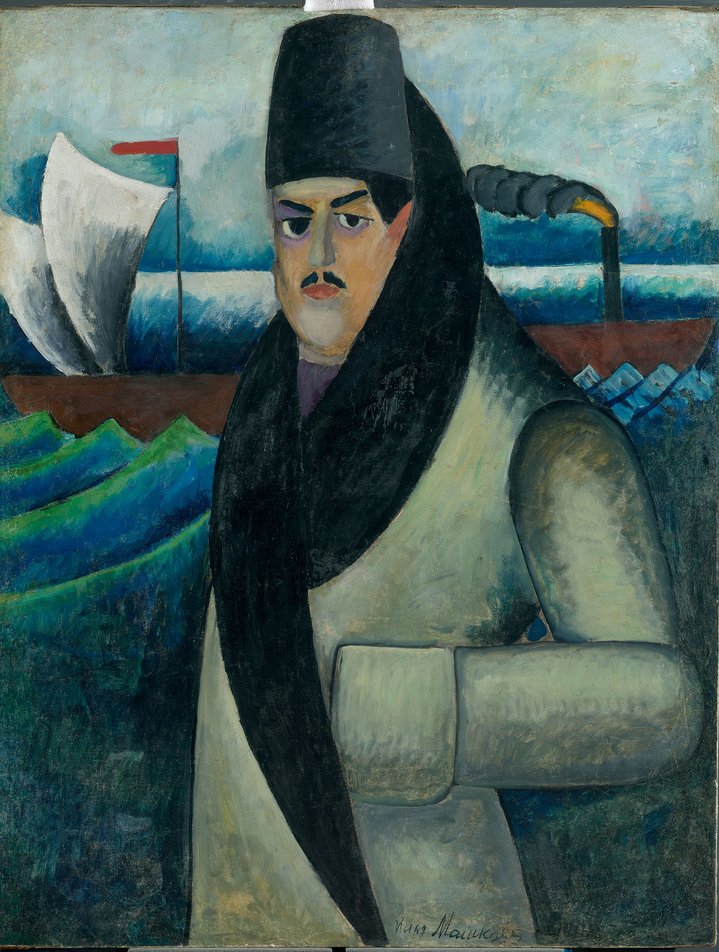

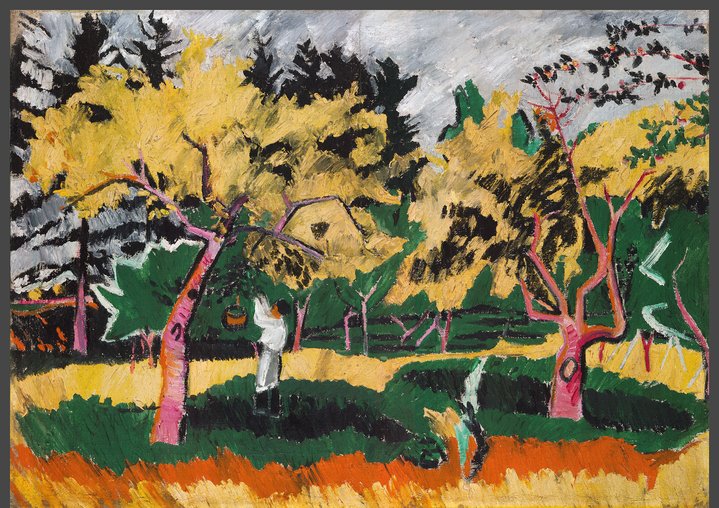

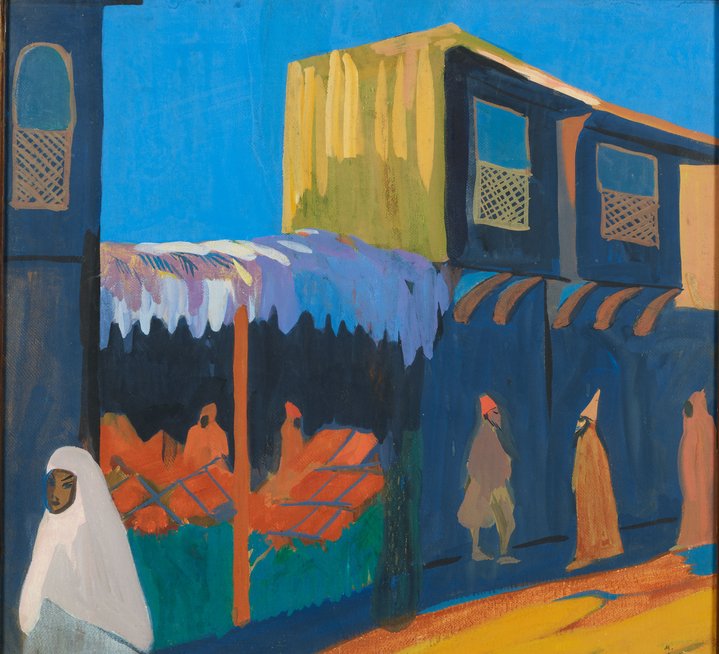

Baldassari invites us to observe the close interaction between French and Russian artists, launched by the Morozov brothers. Here, Martiros Saryan (1880–1972) hangs side by side with Bonnard and Munch, Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) with Andre Derain, Ilya Mashkov (1881–1944), Pyotr Konchalovsky (1876–1956) and Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964) with Cezanne, Mikhail Vrubel and Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) with Picasso, Sergei Konenkov with Maillol. And that famous portrait by Valentin Serov beloved by all Russian art students of Ivan Morozov sitting in front of Matisse’s ‘Fruit and Bronze’ is finally neighbouring its “background”. And so, we can witness with our own eyes just how the Morozovs’ collector vision germinated on Russian soil. To better illustrate the French influence, Baldassari went above the brief to include other works by Ilya Mashkov and Pyotr Konchalovsky that did not belong to Morozovs’ collection. ‘Self-Portrait and Portrait of Pyotr Konchalovsky’ by Mashkov she boldly juxtaposes with ‘Young Acrobat on a Ball’ by Picasso, drawing attention to the blending of influences. Vrubel’s symbolist monumental painting ‘The Lilac’ becomes another counterpoint to the exhibition, literally tearing up the Impressionist row of landscapes by Pissarro, Sisley, Renoir, Bonnard, Corot and Monet.

The final chord of this exhibition is a tall gallery reproducing for the first and only time the Music room in Ivan Morozov’s mansion, with seven panels by Maurice Denis. Unlike the room meticulously replicated in the Hermitage two years ago, its contours and the outlines of the furniture are represented here in neutral tones, directing emphasis right onto Denis’ painting cycle and accompanying ceramic vases. Moreover, the panels from the Hermitage are finally reunited with the four sculptures by Maillol from the Pushkin Museum. Despite the scope and intensity of this cycle, Baldassari, in collaboration with exhibition architect Jean-Francois Bodin, manages again to let the artworks breathe thanks to the open ceiling space and to a roof lantern up above.

Leaving the last hall, it is as if we are exiting the mansion of Ivan Morozov itself. This ephemeral house will cease to exist after the exhibition, but it will surely long remain in the memory of the public. After the names of the Morozov art dynasty had been ignored for half a century, historical justice continues to be restored here in Paris, following the book ‘Morozov: The Story of a Family and a Lost Collection’ (2018) by Natalia Semenova and the recent exhibition at the Hermitage (2019). The result of many years of relentless international work is summarized in the huge catalogue published by Gallimard editions and the Louis Vuitton Foundation and consists of many previously unpublished documents and texts of great research interest.

The Morozov collection. Icons of modern art

Paris, France

September 22, 2021 – February 22, 2022