Inbetween East and Orient

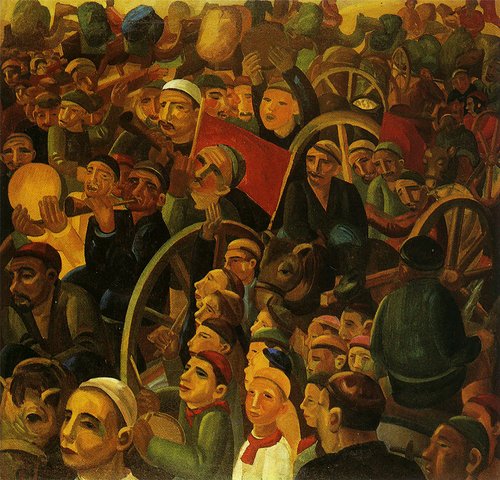

The Way to the East. Russian Artists in Central Asia . Exhibition view. Moscow, 2025. Courtesy of the State Tretyakov Gallery

The State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow is inviting its visitors on a pilgrimage through Central Asia which brings surprising insights into the art of Soviet Orientalism. ‘The Way to the East’ exhibition is an extensive survey of a cultural landscape at once familiar and yet still unexplored.

‘The Way to the East’ was five years in the making and will be open to the public for five months. On show is a trove of paintings, works on paper and sculptures which come from numerous institutional and private Russian collections, including the Tretyakov Gallery, the Russian Museum, the State Historical Museum, the Orenburg Regional Museum of Fine Arts and the Galeyev Gallery among others. But unlike most of the other mega exhibition projects at the Tretyakov gallery over the past few years, it is perhaps too deep and nuanced for general consumption.

The result of years’ long, indepth research means that the exhibition goers need to delve deeply into Russian art of the first half of the 20th century. The last show at the Tretyakov that can be compared in scope with this new exhibition was called ‘Someone 1917’ which took place in 2017-18, a different historical era. Yet whether or not ‘The Way to the East’ will be a crowd pleaser and box office success is perhaps less relevant than an assessment of its scholarly significance, its conceptual integrity and even its reflection of a political moment in time.

Although works have been borrowed from numerous sources, the exhibition relies primarily on the Tretyakov Gallery's own collection, in which curator Igor Smekalov discovered many works which had in fact been made in Soviet Central Asia. There are textbook pieces, such as the 1924 ‘Pomegranate Teahouse’ by Alexander Volkov (1886–1957), one of the most popular avant-garde works today which is usually on permanent display. Or ‘Khiva Girl’ (1931) by Pavel Benkov (1879–1949), a painting which is never absent from any Soviet publications on ‘the fine art of the Uzbek SSR’. Alexander Volkov and Pavel Benkov were two protagonists of the new art: one in Tashkent, the other in Samarkand, one a vivid avant-gardist, the other an ardent realist; they embodied different facets of the new art that Soviet power brought to Turkestan. Because what was new in the 1920s in the former colonies was not only the art of modernism, but also the art of realism, as well as any other type or genre which then existed in Europe.

The Tretyakov Gallery’s collection is so vast that curators can draw from it for years without repeating themselves. Amajor revelation in this exhibition are works that were purchased back in the 1930s but have never been exhibited since then like a huge canvas by Stepan Karpov (1890–1929) ‘Blacksmiths. Samarkand’ (1925) or a small painting on cardboard by Mikhail Kurzin (1888 – 1957) ‘Red Teahouse’ (1930). One is an example of an orientalist salon, the other is a neo-primitive work, inspired by the lubok. Here are just two examples of the difference in approaches to representation. Russian artists brought to the East those multidirectional tendencies that were characteristic of the Soviet art of the 1920-30s.

‘East’ in the title of the exhibition refers to Soviet Central Asia and is not a geographical term. Obviously, for Mikhail Kurzin, a native of Barnaul, a city in the south of Siberia, Tashkent was the west. But it is also a spiritual concept – ‘The Way to the East’ in the sense used by Hermann Hesse, that is, ‘Pilgrimage to the Land of the East.’ It is clear that for Alexander Volkov, a Russian native of New Margelan (modern Fergana, Uzbekistan), it was not a ‘journey’ in the literal sense of the word, but a way to comprehend the art of the East and through this to discover his own vision. And here we come across the main conceptual contradiction in the exhibition – the contradiction between Orientalism and essentialism, i.e. between an external and internal understanding of the East, between describing the East and turning oneself into the East.

Friends recalled that Usto Mumin (Alexander Nikolaev, 1897–1957) could spend hours or even days immobile, immersing himself in himself. Usto Mumin went from revolutionary romance to Sufi mysticism, although very far from the moral ideals of futuwwa: his aesthetic ideal was connected with ‘bachism’ – a form of relationship between adult men and young men common in Khiva, Bukhara and Kokand before the Soviet regime. The current exhibition in the Tretyakov Gallery is limited to two small portraits of a young man and a boy from the collection of the State Museum of Oriental Art in Moscow, almost invisible in the exhibition, although Usto Mumin is one of the brightest artists of the ‘Turkestan avant-garde’, and his programme work ‘The Story of a Young Man Pomegranate Mouth’ (1920s) from the same collection was the centre of the exhibition ‘Touched by the Sun’ at the Alexander Solzhenitsyn House of Russian Abroad on Moscow in 2023–2024. But, obviously, quod licet Jovi, non licet bovi (what is allowed to the bull is not allowed to Jupiter). That is, what a small museum can get away with, the main state museum of Russian art can no longer allow.

‘Turkestan avant-garde’ is a term coined by art historian Tigran Mkrtychev. An exhibition of the same name, held at the Museum of Oriental Art in Moscow in 2009 under his curatorship, revealed to Russian exhibition goers the different types of Soviet modernism in Central Asia. Over the past fifteen years this theme has become fashionable, and since then there has not been a year in which Moscow has not hosted an exhibition in one way or another related to this subject. But Soviet Orientalism does not often attract cutting edge curators of contemporary culture. This new approach at the Tretyakov Gallery is perhaps the first to analyse different types of artistic tourism – not only the spatial visions of Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (1878–1939) and Alexander Samokhvalov (1894–1971), but also the ethnographic subjects of Pyotr Kotov (1889–1953) and Vasily Rozhdestvensky (1884–1963). The exhibition catalogue has scholarly and academic value which is still lacking in the understanding of Soviet art in Central Asia. Although it goes without saying that the catalogue lacks a conceptual framework in the form of postcolonial theory.

The Way to the East. Russian Artists in Central Asia

Moscow, Russia

17 April – 28 September 2025.