Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: revealing and hiding truths

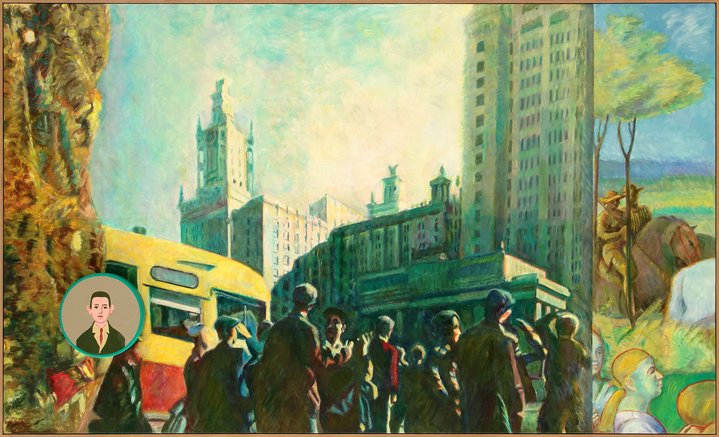

As the Russian artist couple that managed to make the esoteric language of Moscow Conceptualism transparent to a global audience, the Kabakovs re-define the notion of reductionism in their latest exhibition in Dallas.

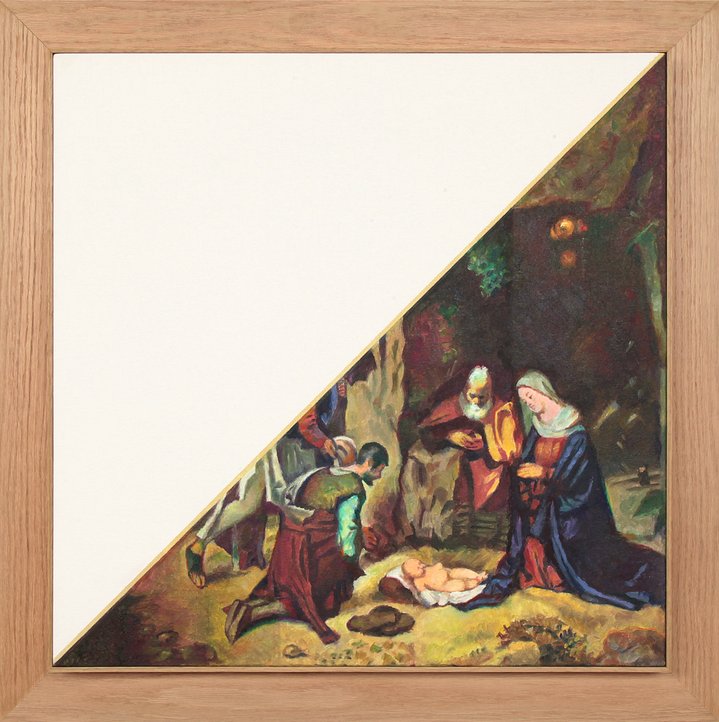

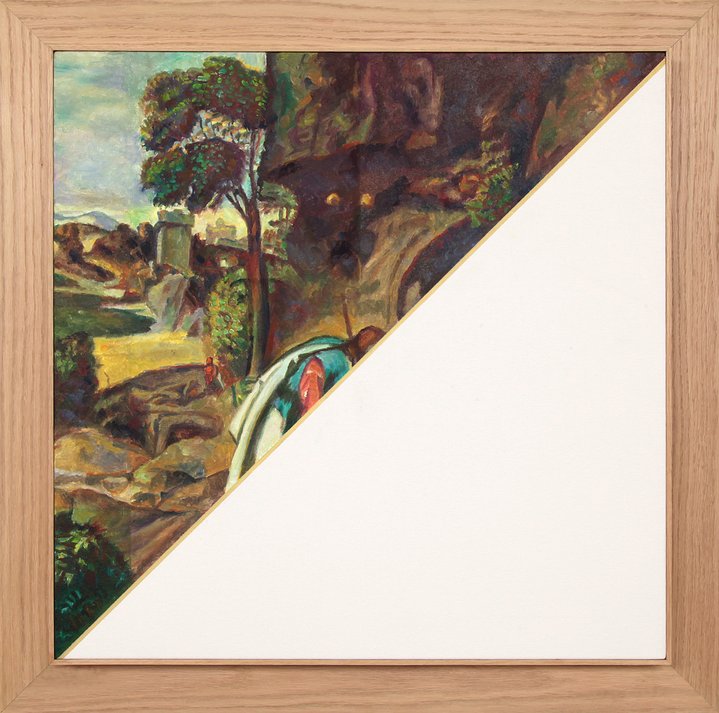

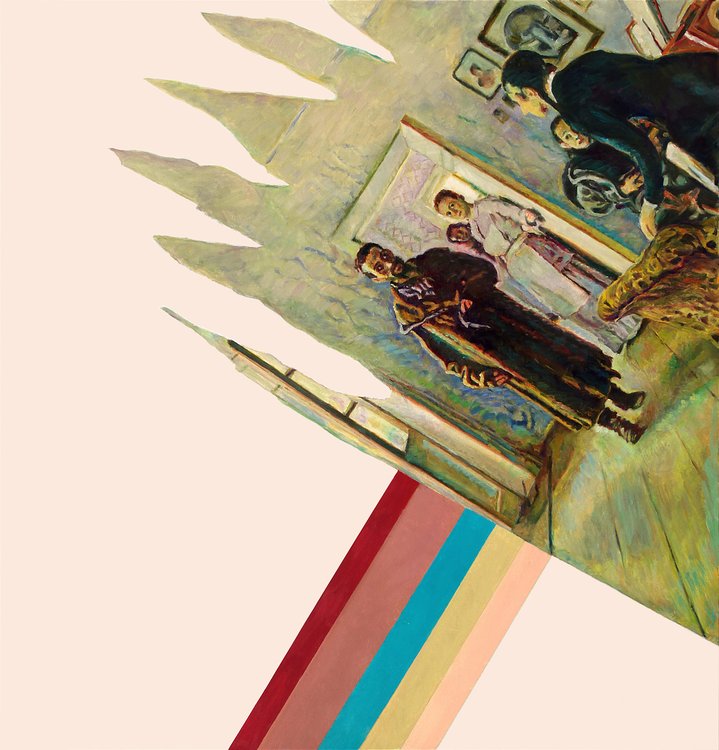

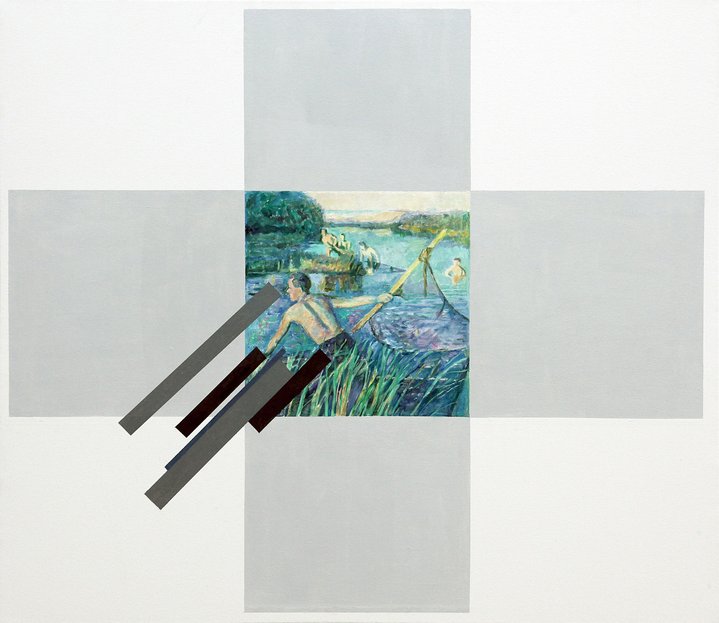

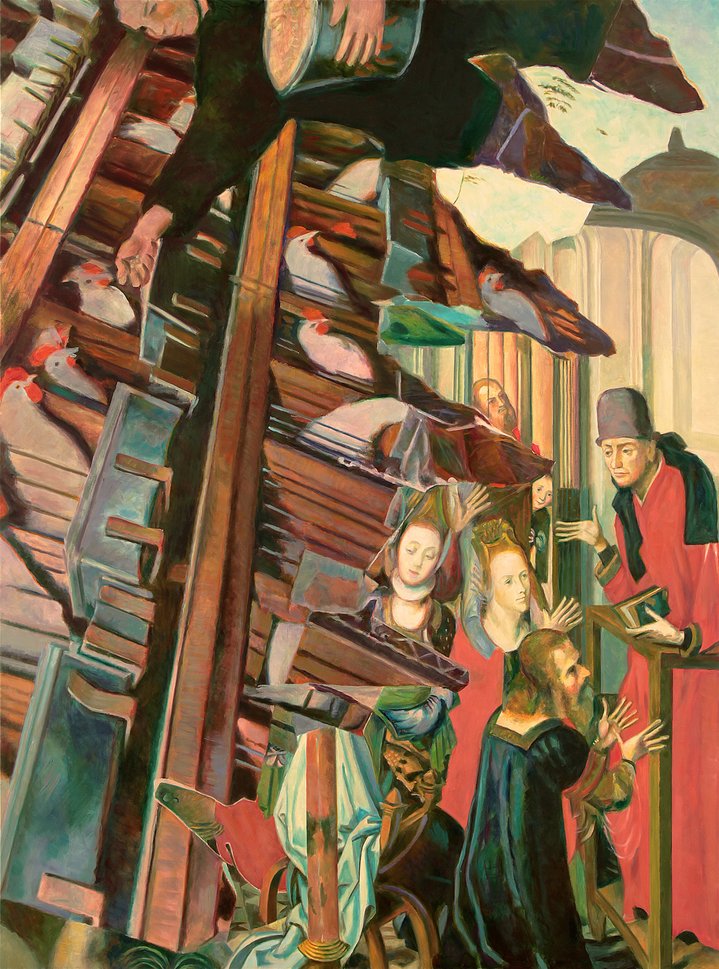

Do you know when someone is telling the truth? How do you work it out? Can you tell whether I am lying when I declare that Ilya (b. 1933) and Emilia (b. 1945) Kabakov’s exhibition ‘paintings about paintings’ at Dallas Contemporary proves that they are not painters? Their real medium is not paint: their building material is experience, building blocks of experience.

Though they have been among the few contemporary Russian artists to succeed in the American market, the Kabakovs’ success has not yet been unconditional. Most Americans (and indeed plenty of Europeans) are suitably baffled. I am not convinced that exhibitions like this one in Dallas, one of the very few institutional shows that have been devoted to them over the last thirty years, will help convert the non-believers. Their shows in American museums have not reflected their international reputation: a show at the Hirschhorn back in 1990, then a touring show some ten years later to places like Aspen, Milwaukee and Duke University and, now, Dallas, which though it has installation and interactive work, appears to be primarily a painting show.

To non-Russian eyes and hearts, paintings about paintings is a familiar self-indulgent theme that the art world loves so much: art about art. Yet, the Kabakovs have made one of the most moving, down-to-earth works of art of the 20th century: ‘Labyrinth (My Mother’s Album)’, 1990. The work, made out of the experience of Ilya’s old family home, his mother’s life and his uncle’s photographs, is not totally straightforward. It is one long corridor, but it is a maze. Ilya sums up this work frighteningly neatly: “When I glance back, to my past life, one of the main images which everything always reduces to is the corridor. A multitude of corridors has haunted me all my life – straight ones, long ones, short ones, narrow ones, twisting ones. But, in my imagination, they are all poorly lit and are always windowless and with closed or semi-closed doors along both sides. And along them, either I am led, or I am searching for something and I don’t know in which room. Of course, it’s as though the main experience of my life is combined in this sensation of myself in the corridor.”

The word that fascinates me is ‘reduces’. The reputation of the Kabakovs is not as reductionists. They are known as builders of installations. And we cannot explain everything away by changes and inadequacies in our languages. We are now all speaking with a different vocabulary from that spoken in the mid-twentieth century art, the heyday of American art theory. Yet, in using the words “everything always reduces to”, they are reaching out for an American understanding. They are explaining that they have something in common with all the great American artists of the mid-twentieth century. They are taking a complicated world and reducing it every bit as much as the great Abstract Expressionists or Minimalists. The Kabakovs are not reductionists in that they minimize the amount of content or paint on their canvases: they don’t. They are not reductionists, because they create constructions that have a faint echo of Donald Judd. Their achievement is to have reduced a work of art to a corridor of shared experience. They have reduced experience to a shared corridor.

Ilya Kabakov is the most famous of the Moscow Conceptualists. Yet, communicating with his audience in Moscow has proved a very different matter from building a relationship with the rest of the world after his move to New York. His original Moscow audience, primarily a pretty small group of other artists, was far more sophisticated than the international art world.

The very words ‘Conceptual art’ imply some kind of communication of a concept. One of the contributions of the Moscow group of artists is that they have de-coupled this idea further from Neo-Platonic thought. The Kabakovs are not trying to impose an ideal concept upon you in any way. They have taken ideas off their pedestal and they come out of our experience of the work of art.

Walking along the dimly lit, drab Kabakov corridors one is able to wander through the maze of one’s own and others’ lives. One is not taken there on a magic carpet. One’s mind has to function and it has to wander: it has to explore. The Kabakovs’ art is not a frictionless conjuring trick. Sometimes it is difficult to put one foot in front of the other on life’s path. Some of us believe that life just happens to us. We have no control. It is just fate. Standing in Labyrinth visitors must make the same decision. Do we move or stay stock still transfixed like a rabbit in the pathetic gaze of a low watt bulb?

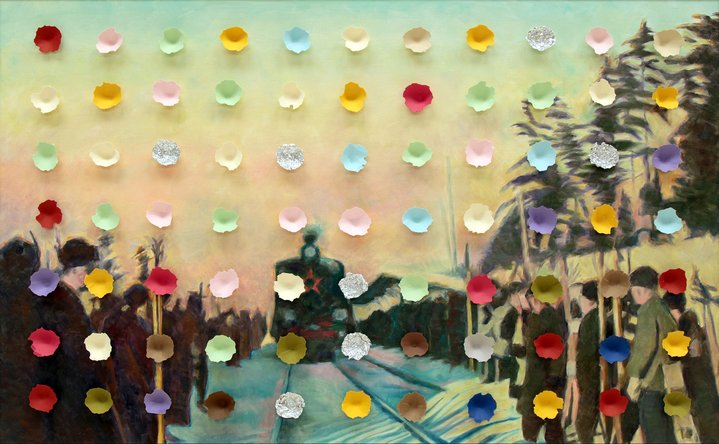

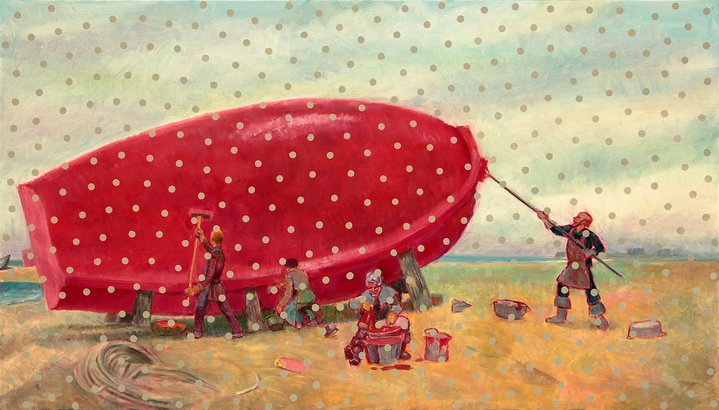

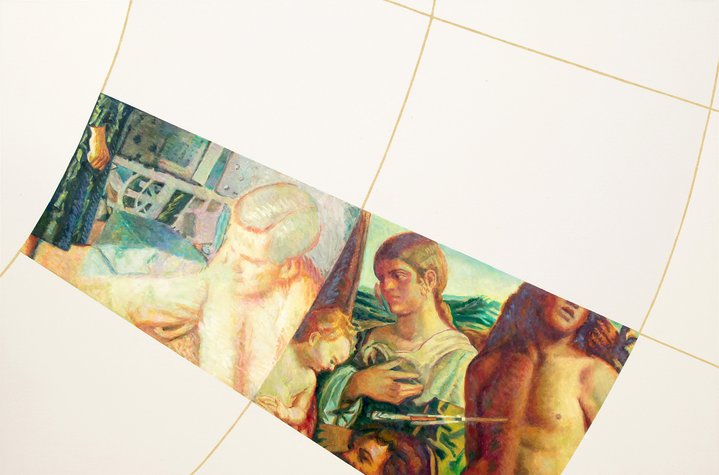

The opening lines of Dallas Contemporary’s press release for the current show are disingenuous (or are they genius)? “For some reason, these paintings remained in the studio until recently. Again dragged out into the light of day, these works filled the artist with revulsion because all their light and energy have disappeared, the paint has yellowed, they are covered with dust, everything has been transformed into boring murk. And a new impulse emerged for the artist: to renew the series, to return to it once again those qualities that it once possessed, to re-inject those feelings of joy and exultation that were previously present and that were supposed to be there.” To achieve this he has sewn on a grid of colourful flowers. It is like looking at a world through bars. Too often we are blinkered, or as Jill Silverman wrily observes, things are “hidden in plain sight”.

The process of telling the truth and telling lies are sometimes very difficult to tell apart. Was the world the Kabakovs are letting us glimpse on the other side of those flower bars always grim? Who supposed it was meant to be full of joy and exultation? These paintings remind me that ‘joy and exultation’ is often deeply locked inside our own heads. The paintings are among the endless keys we need to find to unlock our own thoughts and emotions. But the Kabakovs’ work also supplies warnings. As Ilya says, “One of my continual and often repeating recollections of life until recent times: I am knocking at the door, it opens, I ask something, I get the answer – ‘OK, wait a minute,’ – and the door closes. I stand in the corridor and wait.”

Ilya + Emilia Kabakov. Paintings about Paintings

Dallas, TX, USA

September 26, 2021 – February 13, 2022