How (not) to live forever: the 5th Ural Industrial Biennal of contemporary art

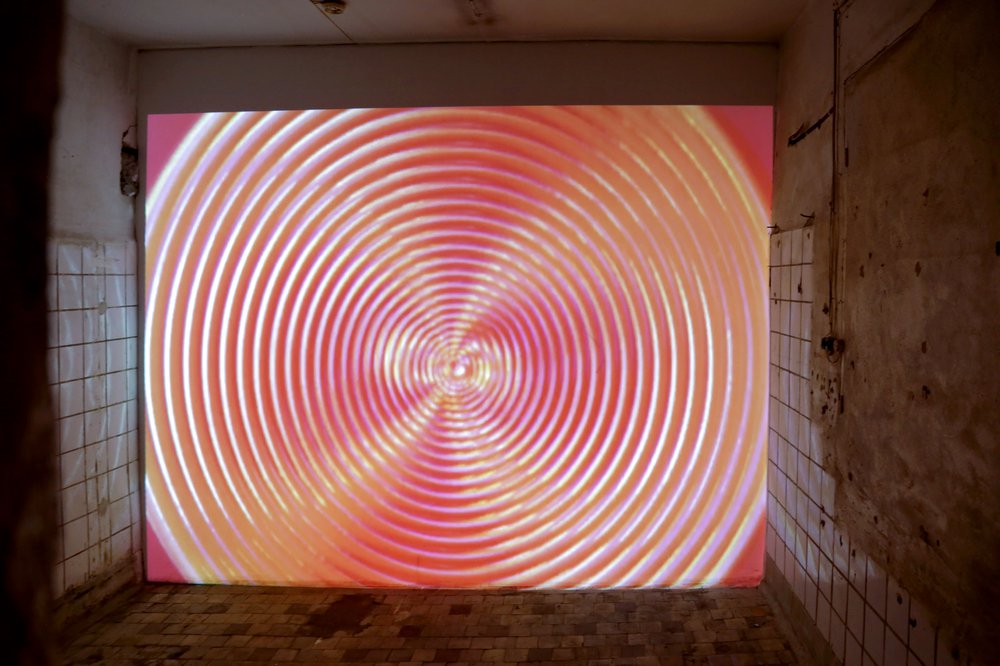

Stan Vanderbeek. Moireing. 2019. Photo by Ekaterina Wagner

The new edition of this popular event in Ekaterinburg, open until December 1, is an unconventional approach to the theme of Immortality.

Eighty kilograms: this is the amount of pollutants per capita in the Sverdlovsk region of Russia. Rumbling past delipidated warehouses and neon shopping centers with a group of journalists who had come to the regional capital of Ekaterinburg for the fifth edition of the Ural Industrial Biennale, I was unsure what troubled me more about the statistic that our guide had just provided: was it the realization that I now had a toxic shadow the size of small man or the fact that I had not noticed him yet?

It may be too cynical to propose a toxic shadow as the logo of this biennale, which combines mostly big names in contemporary art with a few promising new ones to take stock of its theme, “Immortality.” Curator Xiaoyu Weng from New York's Guggenheim Museum asked 75 artists and collectives to help us consider the endless effort required to sustain life and the eventuality of our nonexistence. Indeed, if the concept seems to privilege the desire to defeat death, its content does not shy from the knowledge that such a desire may always be impossible to fulfill.

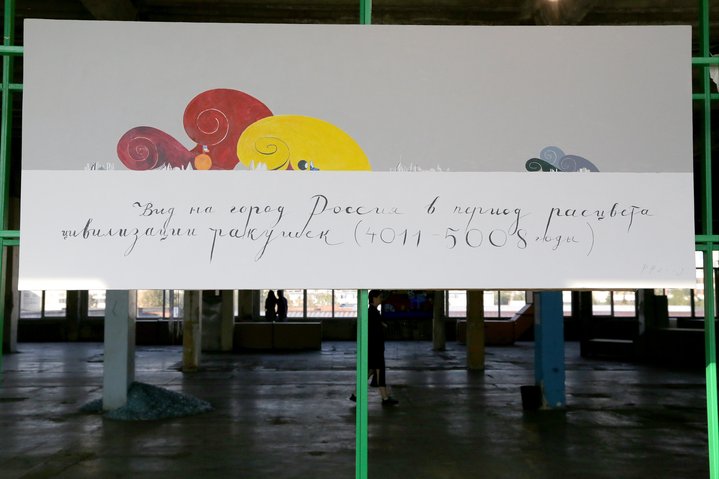

The Ural Industrial Biennale is itself the product of a passing and rebirth. By the end of the last century, the region’s extraction industry was losing ground, allowing the culture industry to move in. This year, the biennale takes place at the Coliseum Cinema and the Ural Optical and Mechanical Plant, which still manufactures glass elements for civilian and military use. Installed on two empty production floors, the main project had little to say about those current spheres of production and instead turns to histories and characters further afield.

The ephemeral activates much of the show, including a Mexican tapete de aserrin that marks the main venue’s hall. Throughout Central America, sawdust carpets are remade annually to mark the holidays of Catholic saints. Here, the vivid flower circle belongs to Jill Magid’s Barragan Archive, an extensive project that began by transforming the ashes of the celebrated Mexican architect Luis Barragan into a diamond in hopes of using it to purchase his professional archive. The project exposes the inability — or unwillingness — of the Mexican government to do so, as well as the material means needed to establish a legacy.

Exhibiting works by known figures is a precarious matter at biennales like this one, which promises contemporary artists a platform while still relying on established works to frame its argument. In general, Weng succeeds in analyzing familiar pieces for a new audience. Experiencing Bruce Conner’s Crossroads (1976), a film that splices together and sets to music 23 shots taken at various speeds of the first underwater atomic bomb test at Bikini Atoll in 1946, made me aware of the role that mass media plays in immortalizing the most devastating events.

Evgeny Antufiev, Lyubov Nalogina and Gala Porras-Kim test the ability of art — and artists — to carve pathways of understanding to long-lost peoples and forgotten objects. Antufiev and Nalogina invent shamanic stories via wall mosaics and discovered “treasures” in "Untitled" (2019). In "Ring Mountain PCNs," Porras-Kim redraws 5,000-year-old images made by members of the Coast Miwok. Decontextualised on a stark white paper, the objects leave us to wonder which histories these fragments gesture towards.

For me, the biennale’s most challenging juxtaposition crystallised in “Ural Mari. No Death,” a special project realised by photographer Fyodor Telkov, photographer and producer Alexander Sorin and anthropologist Natalia Konradova at the Yeltsin Center Art Gallery. Recent photographs document the Mari community, who fled persecution in the Ural region after refusing Orthodoxy in the sixteenth century. Asked to confront both the fragility and adaptability of their culture within the gleaming walls of a museum-cum-library-cum-shopping mall memorialising Boris Yeltsin, I wondered: who gets to be immortal and why? I thought of the sculpture of Lenin that still stands on one of the city’s central plazas. Here was the hubris of believing that a particular person should exist forever, while the lives of countless others remain dispensable. Amid all these images of loss and survival, it seems that the hardest part may actually not be living forever, but rather making life itself worth living.

The 5th Ural Industrial Biennial

Ekaterinburg, Russia

12 September – 1 December 2019