Highlights from the Opaleva Collection Go on View in St. Petersburg

Parallel Universes. From Abstraction to Artifact. Natalia Opaleva’s Collection. Exhibition view at State Russian Museum, 2023. Photo: Vasily Bulanov

In St Petersburg selected works from the collection of non-Conformist art assembled by art patron and founder of the AZ Museum in Moscow, Natalia Opaleva, are being exhibited in a show called 'Parallel Universes'.

This is not the first successful collaboration between the Contemporary Art Department at the Russian Museum headed by Alexander Borovsky (in the late 1990s it became the first contemporary art museum in post-soviet Russia), and the AZ Museum, named after Anatoly Zverev (1931–1986). Last year there was a joint exhibition project of non-conformist portraiture. This time, the current exhibition, called ‘Parallel Universes. From abstraction to artifact’ shows the breadth and depth of what is becoming one of the most fabled collections of Russian art of the second half of the 20th century.

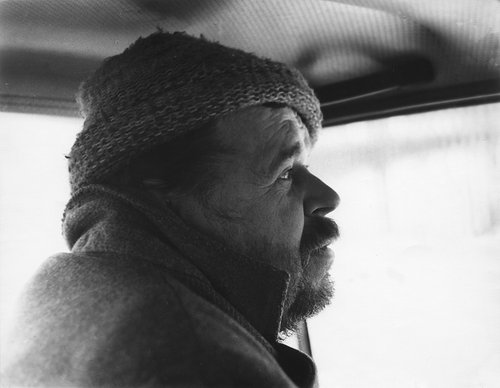

Assembled by Natalia Opaleva, she has been collecting works by non-conformist artists for two decades and has single-handedly built up an impressive collection worthy of any museum. She is known for her highly personal approach being involved on every level of her collecting activities and her strong natural empathy for the artists and their work – ‘Collection as Empathy’ is the title of a text by Alexander Borovsky in the exhibition catalogue. Opaleva has been on the Board of Directors of GV Gold, a gold mining company, since 2001, but her art collection is far from an investment tool, rather it is an expression of her passion and love for the art. It was the work of Anatoly Zverev which she was first drawn to and became the foundation of her collection and the AZ Museum, which she opened a decade ago. Then she collected works of artists from the 1960s and 1970s, and her mission is not only to educate the public today about the art from this era, but also bringing alive the special atmosphere from which this art sprang.

In the vast exhibition spaces in the Russian Museum you walk through over half a century of the history of abstraction in the Soviet Union. The curatorial team led by art director of the AZ Museum, Polina Lobachevskaya, assembled the large and complex material with harmony and balance, highlighting the complicated connections between individual artists, where each is a vivid and sometimes irreconcilable creative personality. The ‘unofficial’ artists in the Soviet Union were obsessed with formalism; their art was primarily the creation of forms, and for this they were persecuted by the authorities. The word ‘formalism’ itself was a dire accusation in a country where artists had to belong to official artist unions, and it was difficult to even buy art materials without a membership card, although this was a minor irritation for the artists who consciously chose to exist independently and defy ideological dictates.

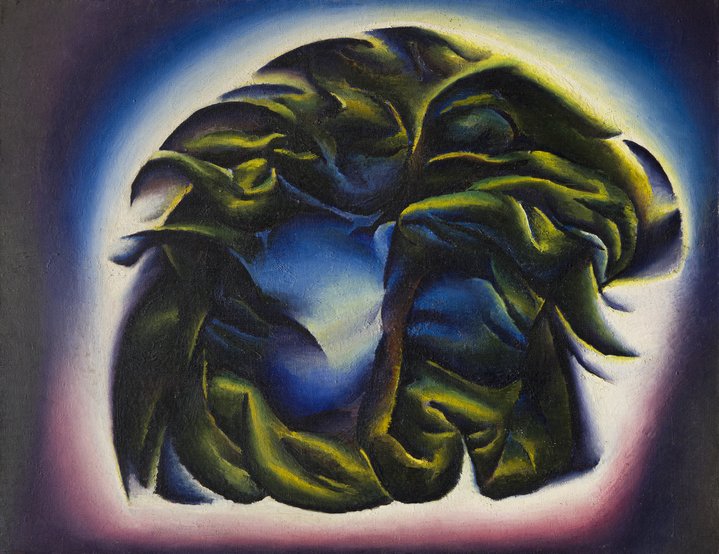

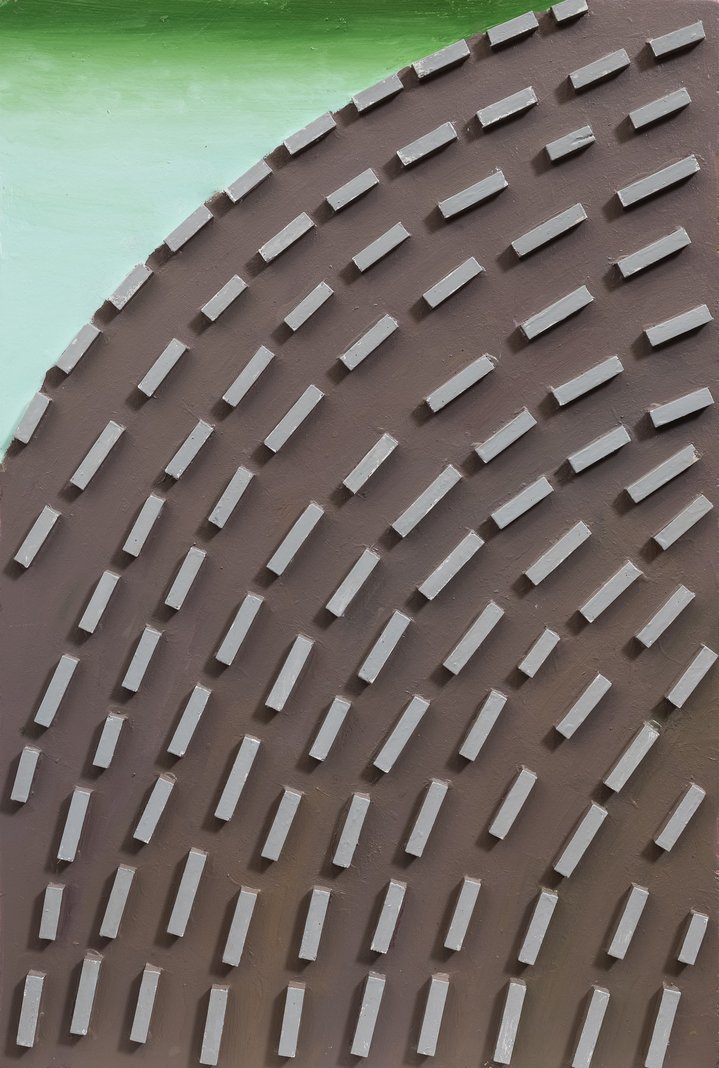

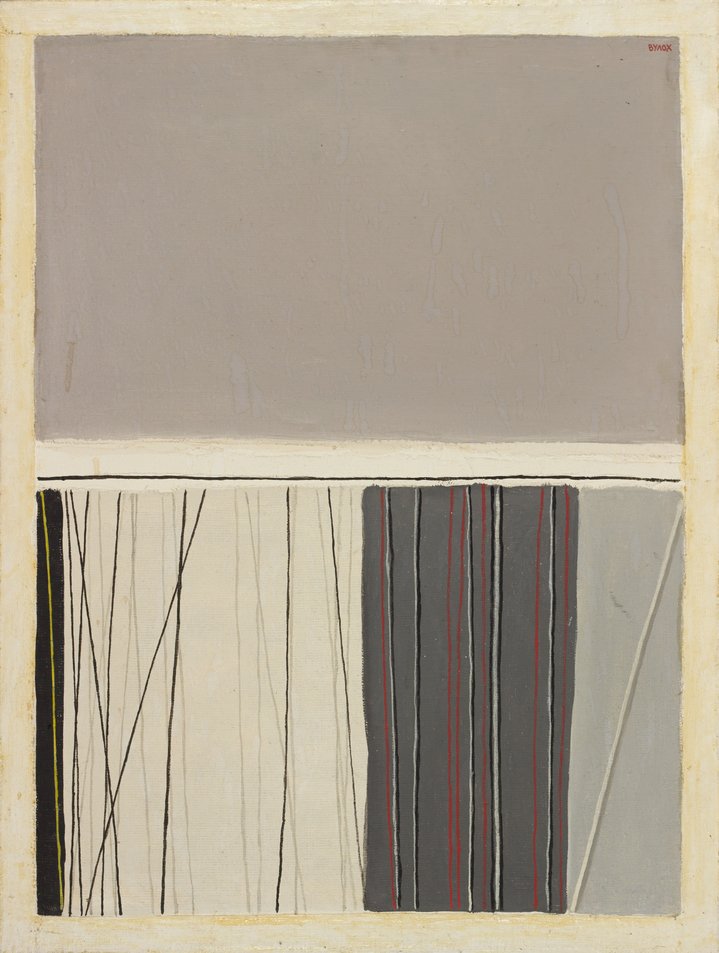

From rare Suprematist compositions of 1958–59 in Anatoly Zverev’s oeuvre, one continuous line goes to Vladimir Nemukhin (1925–2016) and to Yevgeny Rukhin (1943–1976) in the first room, and another to Dmitry Plavinsky (1937–2012) and Boris Sveshnikov (1927–1998). In the next rooms, collage paintings by Pyotr Belenok (1938–1991) are paired with graphic art by Lydia Masterkova (1927–2008) and Rimma Zanevskaya (1930–2021) as a consistent manifestation of white colour and pure light on the road to artistic minimalism. Three paintings by Vladimir Yankilevsky (1938–2018) from various periods face early works by Oleg Tselkov (1934–2021) and Evgeny Mikhnov-Voytenko (1932–1988). Leonid Purygin (1951–1995), Valentina Kropivnitskaya (1924–2008) and Vladimir Yakovlev (1934–1998) together form a magic crystal of pure and naive attitude to the world. The works of our contemporary Platon Infante (b. 1978), who was born as the son of the artist Francisco Infante (b. 1943) and inherits the non-conformist artistic tradition, frame the beginning and the end of the exhibition. This plastic prologue and epilogue with the series ‘Herms’ by Grisha Bruskin (b. 1945) are out of the historical narrative and seem unnecessary, as does the bright orange colour, which designer Anatoly Golyshev chose as a decorative theme throughout.

When compared with American and Western European art there is a chronological lag in Russian art which can be explained by historical reasons. Expressive abstraction was popular in the Russian undeground during the period when Pop Art and conceptual art were fashionable in the rest of the world. It’s an interesting discrepancy for academic art historians today researching the relation between the ‘local’ and the ‘global’ in culture. The turn from critical realism to non-figurative art, which occurred in European painting in the first half of the 1950s under the influence of American abstract expressionism and the success of Jackson Pollock, has its parallel in the history of Russian art, which was deeply influenced by the American exhibition at Sokolniki in 1959, where Anatoliy Zverev and Mikhail Chernyshov (b. 1945), as well as the Soviet public, saw original abstract artworks for the first time. This is where the similarities end, and the differences begin. The fate of almost every artist in the Opaleva collection is marked by the overcoming of obstacles, fearlessness and even heroism – take for example Oskar Rabin (1928–2018), famous for his expressionist landscapes, who in 1974 grabbed hold of the bucket of a bulldozer that moved on artists and their work during the eponymous street exhibition.

Interest in artists of the 1950s and 1980s, whose creative expression was hindered by the authorities up to the point of being pushed into exile, first appeared in Russia during the Perestroika years, in the second half of the 1980s. Today, this art constitutes the ‘golden fund’ of Russian culture, yet the main state museums are far from possessing the best works as they have gone into private collections in Russia and abroad such the Norton Dodge collection, at the Zimmerli Museum, Rutgers University, or the George Costakis collection, most of which is in the museum in Thessaloniki; and some 600 works were acquired by the Opaleva collection in 2013.

Over the past decade a new wave of interest in Soviet non-conformism has been emerging. Due in part to the passing of many of the stars of the era, such as Eduard Steinberg (1937–2012), Vladimir Yankilevsky, Oskar Rabin, and Yuri Zlotnikov (1930–2016), whose legacy and contribution to art are now seen in their entirety. In addition, one of the important issues in the history of Russian art over the last thirty years has been the attempt to combine and reconcile the official and unofficial lines of its development, but it is the interest of the international art market and individual collectors who are setting the historical record straight. This victory won by artists who put creative freedom over submitting to the dictates of political ideology foisted on them from above, should bring hope to the current generation of young artists.

Parallel Universes. From Abstraction to Artifact. Natalia Opaleva’s Collection

St. Petersburg, Russia

3 March – 29 May, 2023