Expressionists, Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider at Tate Modern

Wassily Kandinsky. Improvisation Deluge, 1913. Lenbachhaus Munich. Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957

A myth-busting show at Tate Modern about the Expressionists centred around Vassily Kandinsky and his partner Gabriele Münter and the Blue Rider receives only a lukewarm critical reception in London.

The last show about the Blue Rider at Tate in London was held back in 1960. The absence of a canonical survey on this most important of modern European art groups at the centre of the British art establishment itself gives pause for reflection. If in Britain we have an unquenchable thirst for French modernist art, ought we not sometimes change our compass?

When the Lenbachhaus in Munich approached the curators at Tate Modern several years ago with the idea of an exchange of works – from the Tate would come works from the JMW Turner bequest and from the Lenbachhaus, works from its holdings of Blue Rider cultural heritage much of which came from Gabriele Münter’s own collection – it was rightly lauded as a fresh example of sustainable curation. Transplanting one core collection for another is a way of bringing capsules of art to local audiences that have organically grown elsewhere. The Lenbachhaus is the home of the Blue Rider, and its current director Matthias Mühling, has long been working at presenting this transnational collective in original ways. It seems that with no hinterland in London, this nuanced approach was hard to translate.

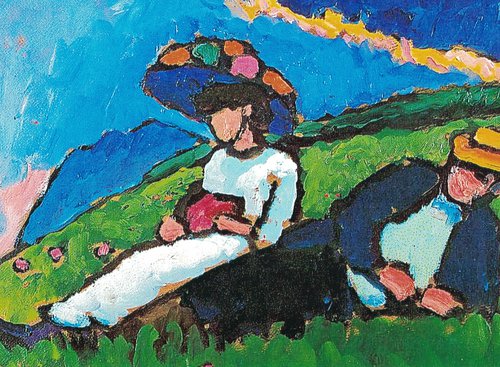

Faced with the cultural vacuum in the nation’s understanding of either German expressionism or the Blue Rider, and faced with the specifics of this loan, as well as working with a mission to frontline female artists, and examine peripheral versus mainstream historiographies and championing diversity over uniformity, Natalia Sidlina who curated the show at Tate collaborating closely with the Lenbachaus curators, carved out a narrative through the Blue Rider, covering all the usual homebases – Murnau, the birth of abstraction, synaesthesia, the science of colour, Goethe and Chevreul – adding in some new fresher perspectives. Yet in addition, she and her curatorial team at Tate took one bold and I think controversial pivot. Traditional histories of the subject take the duo Vassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) and Franz Marc (1880–1916), co-editors of the Blue Rider Almanac, as the core of its DNA. In the show at Tate, everything springs from Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter (1877–1962), in the first decade of the 20th century, partners in life and art. This partnership threads throughout the Tate show: there is the title; the first rooms hung with Münter’s photographs from a journey to Tunisia, and a symbolist early painting by Kandinsky of lovers on horseback; and the provenance itself, because most of the works from the Lenbachhaus came originally from Gabriele Münter’s personal collection including numerous masterpieces created by Kandinsky during the labour and birth of abstraction. Münter took care of them over decades, through the rise and fall of Fascism, Revolution, two world wars and romantic rupture.

Can you talk seriously about the Blue Rider without frontlining Franz Marc? Despite my initial feelings of discomfort there is something reassuringly playful in shifting perspectives, as well as accepting the need for current ideologies around rewriting the role of women in art history. What this show tries to make clear is the extent to which this pair, Kandinsky and Münter were a driving and nurturing force behind the Blue Rider. Münter initially studied under Kandinsky and later they lived a nomadic existance as a romantic couple for several years until they finally settled in Bavaria. By the time she was twenty, Münter had lost both parents, and it was her substantial inheritance that enabled her to buy the house in Murnau which was to become the cradle of the Blue Rider. The couple created together a warm and conducive meeting place for artists, musicians and performers of the day, also by dint of Kandinsky’s background a locus of emigrees from the Russian Empire with whom the couple socialised, such as Alexey Jawlensky (1864–1941) and Marianne Werefkin (1860–1938), Alexander Sacharoff (1886–1963) and Elisabeth Epstein (1879–1956), alongside their German colleagues and this draws attention to the contribution by Russian Kulturträgers to German Expressionism – the locals in Murnau even nicknamed their home the ‘Russian House’.

It was in Murnau that Kandinsky and Marc debated the framework for their almanac. The priority was not on exhibiting together, but to put down their ideas, and share and disseminate them on an international scale, wielding influence across borders, with a focus from North America to Russia and North Europe to the southern reaches of the Russian Empire in present day Ukraine. A large roll call of artists from across many countries contributed to it. The Tate exhibition reveals that that this chapter of German Expressionism was actually not very German or local, as Franz Marc was the only artist who actually came from Bavaria. Ironically it is Kandinsky who is depicted by Münter wearing traditional bavarian Lederhosen as he sits at a table in the Russenhaus in Murnau talking about his new ideas.

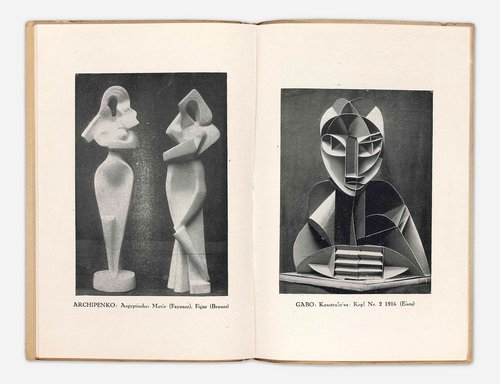

The exhibition catalogue, likewise, reflects a shift away from traditional readings of the Blue Rider group. Arranged kaleidoscopically, assembled under four chapters - Times and Places, Relationships, Studio Practice, and Networking - there are no less than twenty-eight short texts covering both conventional topics as well as an abundance of much lesser-known aspects. Prioritised are socio-historical readings and how the close relationships and networks between the Blue Rider artists serve to reassert the collective, transnational nature of the group, something which is lauded as almost prophetic and germane to our contemporary understanding of art practices, a century later.

Another strand of the Tate’s vivid narrative through the Blue Rider is an exploration of gender fluidity, especially in the personalities of Marianne Werefkin and performance artist Alexander Sacharoff. Unknown today by name until rescued by the Tate show and placed back alongside his contemporaries, anyone familiar with the work of Alexei Jawlensky, will have encountered Sacharoff’s elongated head and effeminate features in the portrayal of his Spanish dancer of 1913, which to those of us familiar with the image brings a fresh dimension to our understanding of it. The Tate curators dedicate a room to Sacharoff, led by a 1909 portrait by Werefkin depicting her friend as an effeminate fin-de-siecle diva holding a flower. Werefkin herself played with gender, forming her ideas around the work of Russian philosopher Vladimir Solovyov who corelated creativity with the ideal of androgny. These gender fluid practices all take place within the space of the performative arts and they add to our understanding of Blue Rider art which valued notions of creative and expressive freedom.

Shifting the perspective onto Kandinsky and Münter not only elevates her contribution but it also enables us to focus more on Kandinsky’s huge presence behind the Blue Rider perhaps more definitevely than traditional histories of the group have done. “Where is the blue horse?” lamented Sunday Times art critic, Waldemar Januszczak, in his review of the show referring to one of Franz Marc’s paintings of a blue horse, a gem of the Lenbachhaus collection, his blue horse paintings are often used in histories on the subject. An oversimplified version is that both Kandinsky and Marc came up with the name for the almanac because they both liked the colour blue, Marc liked horses and Kandinsky Riders. In the end I think Kandinsky wins over, I have always seen the group’s real ethos as reflecting something of a Saint on a horseback fighting evil (ignorance and darkness) in a transcendental experience and Kandinsky’s blue rider feels more like the christian saint George than a bareback rider communing with nature. Kandinsky’s horsemen of the apocalypse, and his Christian eschatology are nestled quietly at the peak of the Tate show, his flight into abstraction, these works which remained with Gabriele Münter until she bequethed them to the Lenbachhaus a few years before she died, are hung together to show us how reality breaks down into pure form and art concerns the spiritual rather than the quotidian or the natural world.

Without his blue horse, and relegated mostly to one room in the show, Marc may not have been the leading light at Tate, but the curators have still used his 1912 masterpiece, ‘Tiger’, as the iconic leading image for the exhibition, on the poster, banners and catalogue cover. It turns out this is also a self-referential homage to the Tate, as Marc’s iconic Tiger was also shown on the exhibition poster of the Blue Rider exhibition in 1960.

Expressionists. Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider

London, UK

25 April – 20 October, 2024