Evgenia Nozhkina: Victims of electricity

‘What Remains Under Water’ an exhibition of work by Evgenia Nozhkina has opened at the Fabrika Centre for Creative Industries in Moscow. Addressing the country’s past, she turns the facts of its grim history into the scale of universal tragedies.

“My grandfather and his family were evicted from the village of Yanovo and it was flooded. He walked through the water and fished things out,” Evgenia Nozhkina (b. 1986) tells some of the stories she heard in her childhood as she explains the theme behind her exhibition. “But after a few days people stopped taking things out of the water, as coffins started floating by: the cemetery was being washed away. And my aunt told me how a few years after we moved away, they were taking a ferry across the river Kama, and they passed coffins and belfries still sticking out of the water.”

This personal memoir is a kind of preamble to Nozhkina’s project ‘What Remains Under Water’. She has brought together works created in different media, but mainly tapestries and small sculptural pieces, which are dedicated to things that actually happened. Although they have no real connection to historical events, these sculptural pieces, woven from old clothes or made from small objects sealed in resin, preserve the colours and textures of everyday objects long since forgotten. And they invite you to reflect on life which has disappeared, on people who are long gone.

In the 1930s at the beginning of the era of industrialisation in the USSR, the Soviet leadership set about transforming the agrarian country into an industrial one. It also coincided with the epoch of Stalin's repressions, in which millions of citizens died, and for those who were not put to death or shot there has been no collective remembrance. However, industrialisation and repression went hand in hand and no where was this more evident than in the construction of hydroelectric electric power stations (GES), which began in this era. This left a big stamp on the fate of Nozhkina’s family.

During the construction of hydropower plants, dozens of towns and hundreds of villages and hamlets were flooded across the nation. Forced migrants, like refugees, the residents became victims not so much of industrial transformation as of the ambitions of the authorities. Because the Soviet hydroelectric power stations were to become the largest in the world. Sixty thousand people lost their homes, among them the artist’s ancestors. When she had covid last autumn, Nozhkina was sitting at home and weaving a tapestry while listening to an audio book called ‘A Farewell to the Motherland’ by Soviet writer Valentin Rasputin. It is the story of just such a flooded village. “I read it as a child,” the artist explains, “but it’s only now that I can compare it with what my grandfather told me when I was 16. I am from Voronezh, my grandfather is from the village of Yanovo, in Siberia, close to Krasnoyarsk. But there is no village of Yanovo now, nor the neighbouring town of Novoselov. I called my relatives who still live in those places, and they remember everything. But it was forbidden to speak about it”.

To accompany this project, Nozhkina gathered heartbreaking stories of people and families affected by the construction of ten of the largest power stations in Russia. All seven thousand of the inhabitants of the once flourishing town of Mologa, near Yaroslavl, which is now called the Russian Atlantis because it sank completely, were moved and those who resisted were sent to the Gulag. Twenty-one thousand people were living in territory flooded to build the Sayano-Shushenskaya hydroelectric power station, the largest in Russia. Among them were the Tuvinians, one of the indigenous peoples of the North, who suffered the most: “First they were asked to move, then they were forced, and threatened. A few years passed, and one night water flowed into the village through canals which had been dug out. For another three or four years, people were left to live on islands sticking out of the water. Then their houses were burned down. The Tuvinians eventually resettled, but their descendants still consider themselves exiles to this day. They used to live on fertile soil, but they were given barren land on which nothing grows.”

If villages were relocated, livestock, cows, goats, sheep, also perished. But so did people. In some towns, Nozhkina learnt that as many as three hundred people refused to move and died. They are not alive to speak about their fates, so by weaving tapestries from old clothes, the artist becomes a voice for the departed. She cuts open a dress or a jacket or trousers and turns them into ‘yarn’. She works with this material on the loom she learnt on as a student at the Art and Graphic Department of the Voronezh Pedagogical Institute. She presented her first tapestry in 2015 at the Biennale of Young Art at Fabrika, “I wove it from fragments of things that surrounded me as a child, trying to overcome my childhood fears”.

Nozhkina is already a successful artist, she has had more than twenty solo exhibitions in Moscow, St. Petersburg and other Russian cities. She has participated in art projects at home and abroad, in dozens of major art events, including biennales, festivals and fairs, creating work around this theme consistently using the same media. In one way or another all of her works deal with the personal stories that make up the country's history.

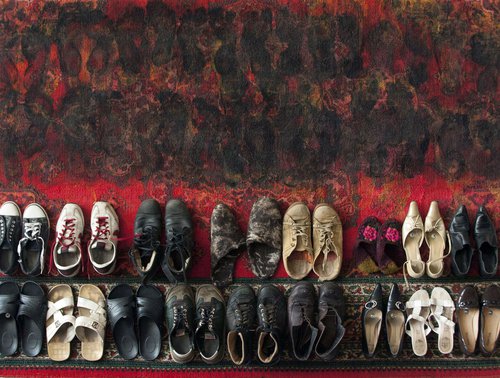

Eschewing a lamentation for the victims and the bitter curses their heirs send to the Komsomol members of the 1930s who resettled these towns and villages, she weaves longing and memories of vanished worlds into her multifaceted carpets. It seems as if they never existed, but when you look at how she has woven clothes into the tapestries, you realize: there they are. She weaves fragments of clothing into rugs, along with buckles and buttons. They sometimes fall off, but the artist immerses them in resin, as if fixing them forever. They almost look like pieces of soap, and these transparent objects are a new part of her practice. In almost all of them you find a key. When people left their houses to be burned, they would lock the front door and throw the key into the water.

The tapestries here on exhibition have the most extraordinary shapes: one is like a bear skin, one a bird, and together they seem to make up a mysterious alphabet. “I cut the dresses in a spiral,” Nozhkina explains, “making them into one 'thread' as if keeping people's memory entact. People who have brought me their clothes come to my exhibitions to look for them in my tapestries. The tapestry which opens the exhibition belongs to the Lipetsk Museum of Applied Folk Art where it was on view. I wove it when I had just started working on the history of these hydropower plants, so it was not very evocative, it was hard for me to read about it all”.

Evgenia Nozhkina: What Remains Under Water

Fabrika Centre for Creative Industries

Moscow, Russia

July 15-31, 2022