Erik Bulatov Has Died in Paris

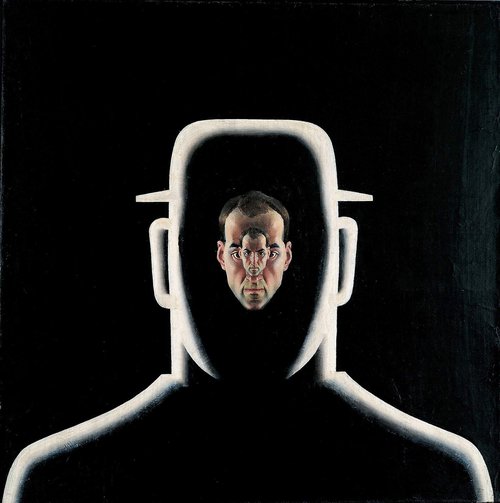

Erik Bulatov at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2016. Courtesy of Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Artist Erik Bulatov passed away in Paris on 9th November. His concept of painting, developed more than half a century ago, remains relevant even today.

Just over two months ago, on 5th September, he had turned 92. Erik Bulatov (1933–2025), one of the leaders of Soviet post-war art, was working up until the very end, his creative power undiminished and still relevant. There is even a sense that he only reached his creative peak in the final decades of his life. His biography is impressive when one leafs through it from the end.

In June of this year Bulatov took part in ‘Unlimited’ at Basel Art fair showing a monumental diptych ‘Forward’. In 2024, his works on paper were exhibited at the Multimedia Art Museum in Moscow. In 2023, the exhibition ‘Horizon. For Erik Bulatov's 90th Birthday’ took place at Nizhny Novgorod Art Museum. At the age of 86, in 2020, Bulatov created a monumental fresco ‘Stop – Go. Barn in Normandy’ on the façade of a metallurgical plant in the town of Vyksa, covering an area of 2,500 square metres. In 2016, when a group of Russian collectors presented a large collection of post-war art to the Pompidou Centre in Paris, assembled as a survey exhibition called ‘Kollektsia! Contemporary Art in the USSR and Russia. 1950–2000’ Bulatov’s works were placed at the heart of the show on a central wall. Commissioned by the Garage Museum in 2015, Bulatov created the monumental diptych ‘Everybody into Our Garage!’ which was presented at an exhibition marking the opening of the Garage’s new building in Gorky Park.

Interest in Erik Bulatov’s work and his popularity especially amongst young people has grown year on year. Curiously, his painting ‘Glory to the Communist Party’ became a meme emblazoned on bags and hoodies. This remains a great mystery because Bulatov’s roots are to be found in the Soviet era, the main source of his imagery, an epoch long consigned to history.

He was born into an intellectual Moscow family and started drawing as a young child. He graduated from the Moscow Secondary Art School with a silver medal and was unconditionally accepted to study at the prestigious Surikov Institute. After university, Bulatov and his closest friend, the artist Oleg Vassiliev (1931–2017), came up with a way to live in a nation where the state was the patron of art, whilst not falling foul of the ideological rules: for six months of the year they worked as children’s books illustrators (their illustrations for Charles Perrault's Fairy Tales are still loved by readers of all ages), and devoted the spring and summer months to their own creativity, working for themselves.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, Bulatov invented a special type of painting that combined three-dimensional imagery with flat typography. The landscape spoke of the world, the letters – of ideology. In this collision of space and text, he did not see irony, but an existential reflection on the dominance of language and the search for a way out beyond Soviet discourse.

During the Soviet period, such artistic experiments were completely incomprehensible. For thirty years, Bulatov “painted for the drawer”. Deprived of the opportunity to exhibit, he remained true to himself.

A major turning point in his life came with perestroika. His first solo exhibition took place in 1988 at the Museum of Fine Arts in Zurich, and the following year an exhibition opened at the Georges Pompidou Centre in Paris. Since then, his fame has only strengthened: participation in the Venice Biennale, a retrospective at the State Tretyakov Gallery in 2006 and a big exhibition at the Moscow Manege in 2014. In August 2025, Erik Bulatov was ranked in first place as the most expensive living Russian artist according to a survey done by The Art Newspaper Russia.

In the 21st century, he began to be perceived differently: not as a Sots-Art artist, but as a philosopher, stoic and visionary. His art is not a cry of protest, but a reflection on boundaries and transcendence, on how to preserve clarity of vision amidst coercion. In paintings like ‘I Live – I See’ or ‘Entrance – No Entrance’, this internal dialogue is visible: a person exists between prohibition and open sky, between word-as-limitation and space-as-freedom. This makes his art universal: he speaks not about Soviet censorship, but about the very nature of boundaries – political, psychological, visual.

Today, in an era oversaturated with signs and information, his work is perceived as almost prophetic. Bulatov showed us how the language of power penetrates the space of perception and how art can expose this mechanism. His paintings are not nostalgia for the USSR, but a reflection on how authorities shape our vision of the world. That is why they remain contemporary and relevant in the 21st century, anywhere in the world.

“Two weeks ago I visited him in Paris. He was cheerful, laughing, joking, delighted that such an important painting for him – a portrait of Natasha – is currently on display at MAMM. We were making plans for the launch of his latest book ‘Erik Bulatov Tells His Story’ and new exhibitions. His eyes were shining. We were thinking about the future,” recalls Olga Sviblova, director of the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow.

According to her, “Bulatov constructed a completely new pictorial space. He showed flat, social space cluttered with slogans and clichés, and behind it revealed another – breaking through the flatness of the canvas, receding into infinity – the space of Spirit and Freedom, a luminous space. Light is the most important element in the artist’s work and life. His last two large paintings are doors: white and black. The main character in them is light, a light that opens behind them, a light that comes towards us.”

“Erik Bulatov created those paintings which we now rightfully consider great and which, without any doubt, changed the history of Russian and Soviet art. Fame came to him quickly once these works were shown in museums across the world. And this fame has remained with him until his last day, and I have no doubt that it will grow with time. Erik is an artist who changed what painting is, uniting it with text in a way that no one had done before him. His achievement lies not in the fact that he created any new movements – although he also did this, seen by many as one of the founders of sots-art, photorealism and hyperrealism in Russian art. Erik was an artist who created those quintessential images that perfectly captured our era over the past half a century,” said gallerist Sergey Popov, who worked with Bulatov for more than two decades and helped to curate several of his solo exhibitions.

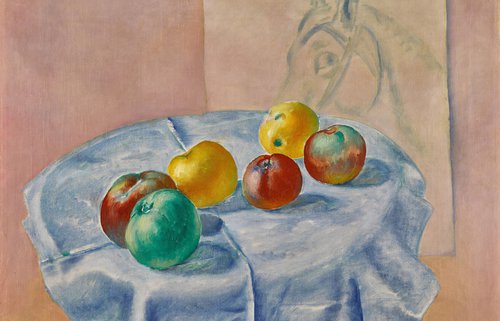

Gallerist Ildar Galeev reflects, “I met Erik Vladimirovich during an exhibition of works by Eva Levina-Rozengolts at my gallery – an artist he knew well and greatly respected. Robert Falk, through his student Eva Levina-Rozengolts, served for Bulatov as an example of the continuity of painterly and spiritual experiment – a lineage of seeking transcendence in painting that Bulatov would later pursue in his own way. It was in his canvases of the early 1960s that his engagement with the surface, his pursuit of the inner luminosity of painting, first emerged as a central concern – a sensual act that would later lead him to analyse how spatial relationships could transform meaning. Agave (1963) entered my collection from the artist Mikhail Mezheninov, who had received the canvas directly from Erik – his friend and kindred spirit.

And today, sad news has come: Erik has left us. He will remain in my memory forever as a radiant, generous, and profoundly kind artist and poet.”

This article was first published on the website of The Art Newspaper Russia on 10 November, 2025.