Threads. Exhibition view. Moscow, 2024. Courtesy of Ruarts Foundation

Embroidered Fortress

The exhibition ‘Threads’ at RuArts Foundation in Moscow shows the relevancy of asking difficult questions in the practice of home needlework, so believes Russian art critic Sergey Khachaturov.

In an atmosphere of strict censorship and repression, the language of Aesop, metaphors, and all kinds of winks and innuendoes have once again become popular. The forms of art which are officially considered marginal and harmless can often come to the rescue and the most interesting events take place in their peripheral field. In the USSR animation and book design were such territories. Avant-garde artists persecuted in totalitarian times went into those spheres, such as students of Rodchenko (1891–1956), Pavel Filonov (1883–1941) and Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935). They created a unique school within these media. Moscow Conceptualism grew out of this school in many ways. Ilya Kabakov (1933–2023), Erik Bulatov (b. 1933), Oleg Vassiliev (1931–2013), Viktor Pivovarov (b. 1937), and Eduard Gorokhovsky (1929–2004) devoted half of their creative lives in the USSR to children's book illustration.

I am certain that today there is something similar going on in the fields of weaving, embroidery and textiles. Until recently, these arts were thought of as applied arts, although today they have become fashionable mainstream. Exhibitions of artists working with textiles, weaving and embroidery take place all over the world. At international shows, including the Venice Biennale, many projects comprise various sewing techniques. The First Textile Biennale was held in Moscow at the municipal Ground Solyanka Gallery. I think that the reason behind the worldwide revival and rehabilitation of this type of creativity is explained by the establishment of object-oriented art, which recognises the autonomy of different media, which becomes a mirror of a different, non-anthropocentric picture of the world. In this new paradigm, it is the craftsman not the genius who acts as a medium of speculative realism, recognising the uniqueness of a reality beyond human control. And in Russia, the theme of weaving and thread is, in my opinion, a refuge for free creativity, in which, as in cartoons or a children's book, it is possible to raise painful questions on an intimate, “non-serious", toy-like, even infantile level. Such a bastion of domestic resistance to the meanness of the world is woven and embroidered.

The RuArts Foundation exhibition features thirty-nine artists from different generations. Curator Nina Gomiashvili has managed to source and borrow historical objects made by Sergei Parajanov (1924–1990) and Timur Novikov (1958–2002). They are placed in a beautiful conversation with works by today's recognised masters such as Ira Korina (b. 1976), Olga Bozhko (b. 1974), Olga Florenskaya (b. 1960), Maria Arendt (b. 1968), Elena Samorodova (b. 1973) and Sergei Sonin (b. 1968)). The challenge is taken up by the young: Egor Fedorichev (b. 1988), Rodion Kitaev (b. 1984), Kristina Pashkova (b. 1992), Anna Lapshinova (b. 1996), Ustina Yakovleva (b. 1987), Tanya Akhmetgalieva (b. 1983). The exhibition itself is based on the collection of the RuArts Foundation. The reference point for curator Nina Gomiashvili was Andersen's fairy tale ‘The Wild Swans’. The main character, Eliza sewed nettle chainmails for her brothers who turned into swans. With the help of the chainmail, the swans could turn back into humans. This return to one's own essence and identity with the help of ephemeral ghostly weaving became the leitmotif of the show.

All of the works on show in the exhibition are surprisingly interesting in their content and complex in their formal characteristics. It is as if the RuArts Foundation presents a certain alternative version of Russian contemporary art to the generally accepted one. It involves all the main trends in contemporary art, from social actionism, conceptualism, post-pop art, Art & Science to the currently fashionable neo-naive and art brute. This alternative version is presented in a soft, intimate, or (and) hallucinogenic, dreamlike version.

It is fortunate that the exhibition begins with works by Timur Novikov. Sergei Parajanov and Olga Florenskaya. Their works mark the landscape of the memory of civilisation and culture, hovering somewhere between the ruins of domestic comfort, the flea market and the folk picture. The intimate involvement with the eternal through the everyday, the man-made and the banal sets the parameters of exceptional trust and charm in dealing with what is on display. The fleecy, rough texture, into which one falls like into a snowdrift, the dreamlike nature of the carpet images draws the viewer in powerfully and at the same time gently and cosily.

Girlish fantasies about the creatures of folklore, domovoys and leshiys (the spirits of home and forest), or princes defined the plots of fairy tales and embroideries of the Romanticism era, when girls sat at work and embroidered by candlelight. Now in the works of female artists these fantasies and fairy tales are combined with images of new mythology and posthumanism. Thus, in Masha Obukhova's (b. 1986) scroll Cocoon, the heroine – a doll – becomes a girl-butterfly, woven into the round dance of the collective female body. This "knitted identity" interestingly rhymes with the themes of the identification of women through dreams, childhood traumas and joys, and the toy world. The works of Annette Messager (b. 1943) and Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) come to mind.

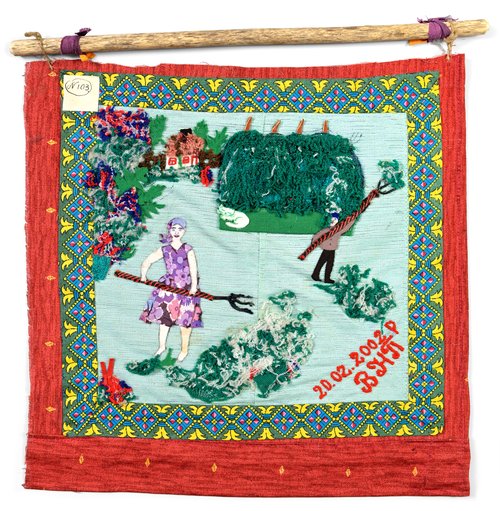

‘Touching heroic’ hypostasis of embroidered contemporary art connects many works. The beginning of this line can be seen in textile collages by Olga Florenskaya, ‘Time. Justice. Melancholy. Hope’. Classical allegory is understood in them as a lubok (folk print). And certain details in these allegories ruthlessly deconstruct the academic image in the face of the tragic agenda of today. For example, Justice is blindfolded, cutting the heads of the right and the guilty with a sword, without thought or sympathy. It is Justice seen through the optics of Retribution.

The history of subcultural marginal communities, all kinds of emblematics, alchemical and magical symbolism, is excellent material for a woven alternative not only to contemporary art, but to civilisation as a whole. The hypnotic, somnambulistic nature of illusion in carpet presentation is maximised. After all, it is a kind of maelstrom of tufted thread flows, which is created by the slow, soporific and paralysing movement of thread and needle. Rodion Kitaev's carpets with the history of rave in the style of a psychedelic art brute gone mad and Katya Isaeva's (b. 1980) ‘Choose Your Player’ were particularly successful as these emblematic structures, which turn common sense inside out. Printed on linen, vintage engravings with cosmogonic plots and atlases of beasts are stitched with dotted quotes from Jorge Luis Borges about new worlds of fantastic creatures and animals. An exquisite visual aid about the essence of posthumanism and posthorror is assembled.

The projection of the alternative history of art and civilisation into the history of Russia is supported and crowned by an excellent series of banners by Elena Samorodova and Sergey Sonin dedicated to the Russian country estate and the utopian Indian campaign of Russian Emperor Paul I in alliance with Napoleon. The quilts are embroidered with fantastically beautiful worlds in which the outlandish trophies of Eastern civilisation are incorporated into Empire-era parades. Here is Paul I riding an elephant. Here is Napoleon riding a camel. A whimsical illusion is embroidered, fragile and delicate like Meissen rocaille porcelain. It allows us to expose the imperial pretensions inside a children's fairy tale and, at least in the family circle, to protect our sanity from them.