Criticism without Analysis: How (Not) to Look at Soviet Constructivist Photography

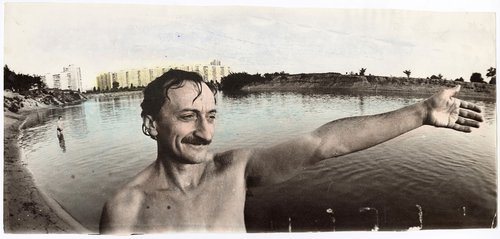

Let’s Begin Creative Discussion. Constructivist Photography of ROPF and Oktyabr’. Exhibition view. Moscow, 2025. Photo by Daniil Annenkov. Courtesy of Zotov Centre

The Zotov art centre in Moscow has curated an exhibition about two rival groups of Constructivist photographers with a focus also on how their rivalry was reflected in the press of the time. Art critic and curator Mikhail Sidlin wonders if this show can really help contemporary Russian audiences to understand what “creative discussion” in photography of the 1930s really meant.

A new exhibition at the Zotov Centre in Moscow about Soviet photography at the turn of the 1920s and 30s reflects the huge popularity today in Russia for art from the pre-war period – last year the same institution also curated the exhibition ‘Rodchenko. Personal’, which essentially said nothing new about this most famous and widely shown Soviet photographer. The current exhibition, titled ‘Let’s Begin Creative Discussion. Constructivist Photography of ROPF and Oktyabr’, impressively brings together some one hundred and ten works of art from major Russian state collections including the State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, the Russian National Library and the Multimedia Art Museum in Moscow (MAMM).

ROPF and ‘Oktyabr’ were two artistic groups that existed in the late 1920s and early 1930s. ‘The All-Russian Association of Workers of New Types of Artistic Labour 'October'’ (1928–1932) included architects, cinematographers, painters among others, a broad catch-all organisation, and its photographic section was created in 1929 by four photographers: Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956), Mikhail Kaufman (1897–1980), Vladimir Gryuntal (1898–1963) and Eleazar Langman (1895–1940). ‘The Declaration of the Initiative Group of ROPF, Russian Association of Proletarian Photo Reporters’ was published in 1931 in the magazine ‘Proletarian Photo’ under the headline ‘Let’s Begin Creative Discussion’ – from which the exhibition at the Zotov takes its name. This declaration was signed by Semyon Fridlyand (1905–1964), Arkady Shaikhet (1898–1959), Max Alpert (1899–1980) and Roman Karmen (1906–1978), among others. Both organisations ceased their activities in 1932, when the Politburo issued a decree “On the Restructuring of Literary and Artistic Organisations”, which resulted in the dissolution of all independent groups in the Soviet Union.

Soviet photography produced during the Stalin Renaissance has been exhaustively shown in public but lacks adequate art historical criticism. Despite the popularity of this subject and the substantial number of monographs on individual artists, there are almost no conceptual exhibitions that examine deeply its foundations, a situation which seems unlikely to change any time soon. And looking at the example of this new show at the Zotov Centre makes it easy to explain why.

The main problem is to do with a lack of distance, specifically, it is about trusting the opinions of a past era about itself. As a result, the theme overshadows the material. The material in the current exhibition proves that the aesthetic differences between ROPF and Oktyabr’ were insignificant. Both made use of angle, close-up, and created works in various series. That is, the dispute between the photographers was not artistic but ideological. However, to talk about their ideology, one needs to understand and analyse its meaning. This is not so difficult to do using the example of the iconic 1931 photoshoot ‘24 Hours in the Life of a Moscow Working Family’ created by ROPF members Arkady Shaikhet, Semyon Alpert, and Solomon Tules.

The members of ROPF claimed they were engaged in photojournalism and the Zotov exhibition echoes them in this. An anonymous exhibition text tells us that “For the Soviet authorities, ROPF’s production turned out to be too truthful”. But this does not apply at all to their most famous ‘Filippov Series’, which is Soviet propaganda in its most undiluted form. The life of a working family unfolds before the viewer. This family has “their own home kitchen”; “there is a laundry room in the building"; “the Filippovs buy a suit for their eldest son at the factory cooperative”, and their youngest son “Vitya comes under the complete control of the directors of the children's town”. Nowhere does it reveal in this current exhibition that most workers at the time lived in barracks and dugouts, that it was impossible to buy underpants (let alone a suit) in the shops, and that one's own home kitchen and a laundry room in the building were unattainable dreams for people who lived using a shared outdoor hole-in-the-ground toilet. Soviet reportage did not function in a mode of truthfulness, instead it was about visual agitation by photographing specially selected people in carefully selected circumstances.

The exhibition at Zotov recycles the old Soviet myth about Soviet photography. Because any narrative about ideology without proper analysis turns into uncritical reproduction. Most Russian exhibitions about Soviet photography are guilty of this approach. The only thing that distinguishes Zotov is that it also reproduces the Soviet myth about criticism. And here a second problem arises – a confusion in definitions. “Creative discussion” was a specific definition commonly used in the Soviet era, which was not creative, but ideological. And “criticism” was not artistic criticism, but public ridicule, reproach, and accusation, with a political pretext.

“As for the photographs of young pioneers by A. Rodchenko, one might think they are from a White Guard magazine” (Comrade Rivkis, moulder at the Kalinin factory). “We looked at the pioneer playing the bugle with disgust... The face of a normal person is turned into the face of a freak, and why?” (members of an amateur photography club of a state farm named after Comrade Stalin (formerly ‘Khutorok’)). The juxtaposition of the “ugly” versus the “normal”, and the “White Guard” versus the “proletarian”, essentially represents a normalising discourse characteristic of the era: the Soviet version of condemning so-called “degenerate art”. But it is impossible to consider this discourse in its own terms.

Recreating the atmosphere of the Stalin era has become a fashionable cultural theme in recent years due to Russia's obvious backsliding in time. But this only creates new meanings when coupled with emotional involvement, dramatic action, and intellectual understanding. For instance, the walkthrough performance ‘Red Wolfram’ at Electrozavod, which for four years in the premises of the former MELZ (Moscow Electric Lamp Factory) told the story of its foreign workers in the 1930s, ended with all spectators lined up in one line in a gloomy courtyard with no exit. And this was a clear finale. For some participants in the lively discussions about photography, things ended the same way. Leonid Mezhericher (1898–1938), the most active photography critic of the 1920s and 1930s, was executed in 1938. But you will not find this out at this show.

The exhibition at the Zotov Centre is divided into two parts, one for Oktyabr’, the other ROPF. But the leading question for the hapless exhibition goers, pasted on a board at the entrance to both spaces asking “who better reflected the time”, seems meaningless, because ultimately both groups performed the same ideological task. And it consisted not in “reflecting the time”, but in propagandising the new Soviet system. VKP(B) (Communist party), GPU (subsequently renamed NKVD, KGB and FSB), GULAG – these are acronyms that you will not see or hear in this current exhibition, although without them it is surely impossible to understand the conceptual framework of Soviet photography at the turn of the thirties.

Let’s Begin Creative Discussion. Constructivist Photography of ROPF and Oktyabr’.

Moscow, Russia

25 April – 20 July 2025