Costakis of the Desert: a New Book on Igor Savitsky

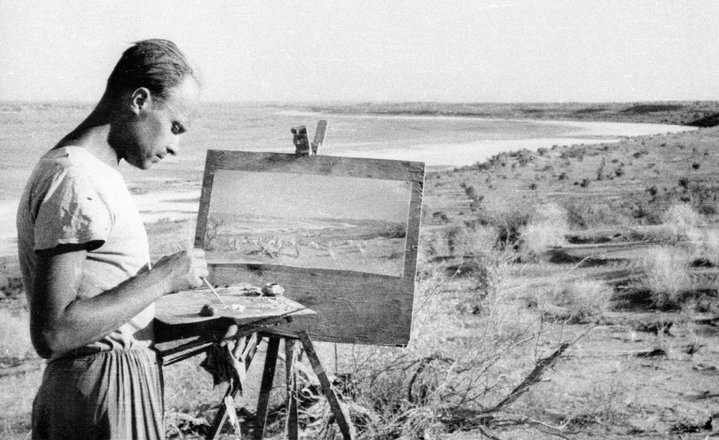

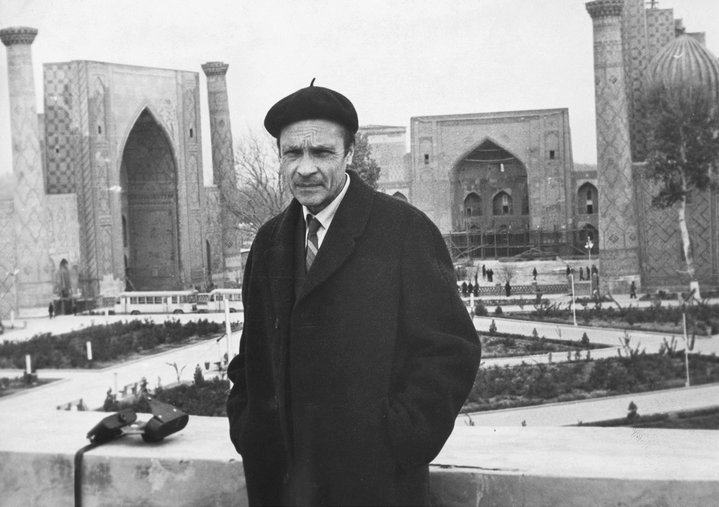

Igor Savitsky, 1950s. Souvenirs of Savitsky. Courtesy of Baktria Press and Nukus Museum

A collection of memoirs on the legendary director of Nukus museum in Uzbekistan, who managed to amass an extensive collection of Russian avant-garde in the era when it was banned by Soviet authorities, has recently been published in English by Baktria Press.

A blazing fire engulfs a family home in Ukraine, flames consume the antique furniture, textiles, works of art, books, all the cultural treasures held within… It is a traumatic image from over a century ago, imprinted on the imagination of a very young child, Igor Savitsky (1915–1984), the destructive impact of the 1917 revolution. He would grow up to dedicate his life to restoring, preserving and safeguarding cultural heritage.

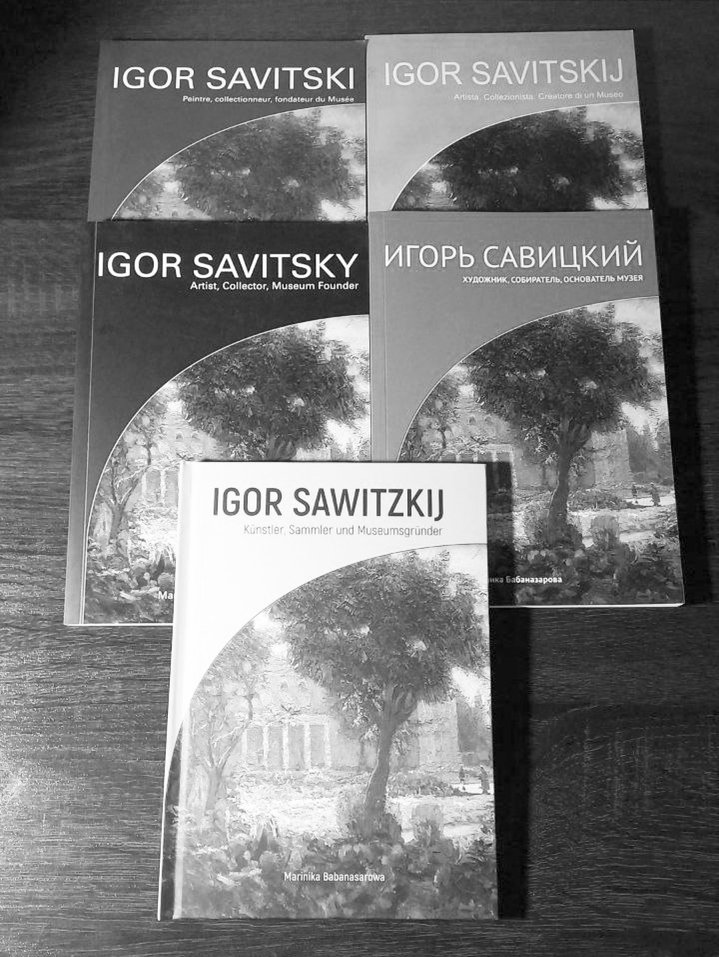

This is one of the vivid episodes revealed in a new compendium of reminiscences about this idiosyncratic collector (Ed. M. Babanazarova, Souvenirs of Savitsky, 2021, Baktria Press, Tashkent), famous for creating one of the world’s largest repositories of art in the middle of nowhere: the Uzbek desert. It is now named after him, the Savitsky Museum, in Nukus.

Much later, “during the war, evacuated [to Samarkand, Uzbekistan] and suffering from typhoid and hallucinating, he had had a vision about creating a museum in the East.” – recalls Kira Kiselyova. In 1966 this museum opened, thanks to the single-handed gargantuan efforts of this frail and eccentric art lover who was at its helm. The museum is a sensation, Savitsky managed to amass over 90,000 works of art with an overwhelming proportion of outstanding works of the Russian avant-garde, second only to the Russian Museum, all rescued from the doom and oblivion pronounced on it by Soviet censorship. Though hidden in a faraway corner of Uzbekistan, a double-edged sword, proliferating difficulties which continue to haunt this paradoxical institution today, this exiled location is also what given the museum an unprecedented freedom, far away from the grasp of power.

The phenomenon of art in exile could not be more pertinent today, when artists are once again fleeing their homelands, searching for shelter abroad – Uzbekistan is again harbouring the displaced, having given refuge to over half a million Russian emigres over the past year. Savitsky’s story throws an interesting light on the historical cultural relationship between Russia and Uzbekistan today.

Whereas the museum is well-known, the publication shifts the focus onto the museum’s founder, Igor Savitsky, whose name is obscure outside Russian and Uzbek art circles. This compendium of reminiscences from colleagues, artists and friends reveals episodes from his childhood, his path to become a collector, the founding of the museum, his unusual working methods, the bureaucratic and financial battles he fought to keep the museum afloat, his increasingly failing health which eventually lead to his death.

“His charm, his humanity, his willingness to visit strangers and listen to their problems, created an atmosphere of trust so that people would gladly share their precious works with him, believing he would preserve them for future generations” writes Irina Jdanko. Others recount his completely obsessive, selfless and driven collecting style. He would take hundreds of works by an artist, overlook personal comforts like food and sleep and devote his life to the museum. Constantly in debt and yet unable to stop collecting, the memoirs also provide an insight into the phenomenon of a collector’s mentality, taken over by the overarching life project. “I keep thinking I may end my days in a debtor’s jail after the Museum fails! I really want the Museum building to be completed and for it to catch the eye; I want the Museum’s reputation and the quality of its collection to be known all around the world. Then I can go to prison for some rest and peace!” reveals Savitsky in a letter to his friend and patron, Marat Nurmuhamedov, whose daughter Marinika Babanazarova became Savitsky’s successor as the museum’s director after his death.

Much of his later efforts were concentrated on a new building for the museum. “He played the roles of director, construction worker and cook,” recall his colleagues. And despite encroaching health problems he would plough on, unable to stop. Accounts recall how he would come to the viewing of a painting with blood leaking through his bandage, “He was melting like wax, but still working at a brutal pace.” Savitsky’s personal correspondence, included in this volume, reveals his struggle to keep the museum afloat, drowing in hopeless bureaucracy, destitution. “But art blooms like a wildflower: it is impossible to eradicate art or to restrict it to officially imposed paradigms, from where it pops out in all directions. This gives us hope and strength for continuing albeit futile Don Quixotesque heroic activity. We are all such romantics”writes Savitsky a year before his death in 1984.

Savitsky was also a painter himself, a skilled electrician, a restorer, archaeologist and ethnographer. He preserved a huge amount of folk art objects from Karakalpakstan and he saw applied art as “the source of artistic expression.” He wanted to set up a workshop dedicated to preserving and passing on artisanal knowledge. He also served as a catalyst for the Karakalpak art movement, supporting and guiding local artists, eventually founding the Karakalpak branch of the Artists Union. His devotion to the local community, its traditions and livelihood, are often overlooked in narratives which foreground the popular avant-garde he rescued, the book serves to redress this with most contributors being colleagues and friends from Uzbekistan.

Despite the truly phenomenal circumstances of the museum, and the standout personality of its founder, this compendium seems to err on the side of caution in divulging his story. Though snippets are revelatory, the narrative lacks a popular appeal, presuming a target audience of specialists in the field. A lack of either emotional or academic engagement, which would give this topic broader appeal, points to a museological mindset still mired in soviet officialdom which precludes independent, creative analysis. The precise opposite of the independent ingenuity which spurred Savitsky’s standout achievement.