Chronicle of the fall of the Moscow Biennale

This year the Moscow Biennale for Contemporary Art, once curated by international stars like Peter Weibel or Nicolas Bourriaud was cloaked in secrecy and then cancelled by the Ministry of Culture on the eve of its opening. Russian Art Focus has investigated the story behind this volte-face.

‘Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel’, so began the post of an anonymous pro-government Russian telegram channel on the morning of the 3rd of November. It continued with an announcement that the 9th Moscow International Biennale of Contemporary Art (which had not been mentioned officially since the 2019 edition), would open in the coming days at the State Tretyakov Gallery on Krymsky Val. The anonymous poster referred to reputational losses of the 2019 edition with quotes from an open letter by artists who had taken part in the previous Biennale and who still had not received their fees from the Biennale of Contemporary Art Foundation, owned by Yulia Muzykantskaya (and it was not just artists: developers, former Biennale employees and even exhibition hall guards had not been paid). The posting also announced that this year’s exhibition was to be dedicated to the theme of patriotism and that there were artists from the Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics taking part (two territories long disputed between Russia and Ukraine which officially became part of Russia after a recent plebiscite in September). This anonymous telegram poster ended with the conclusion that ‘Muzykantskaya has decided that ‘patriotic pathos’ and ‘Donbass artists’ are now an absolution from any sin.’

Just a few hours after this had been posted on telegram (the poster evidently had sources at the heart of the Ministry of Culture; this same channel had published preparatory materials for the international exhibition ‘Diversity United’ at the Tretyakov Gallery, which led to its cancellation, then postponement), the Deputy Director General of the Tretyakov Gallery Sergei Mishin wrote to Yulia Muzykantskaya informing her that ‘the management of the Tretyakov Gallery decides to suspend all work in preparation for the exhibition and the admission of contractors to its premises from 4th of November 2022’. To this, Muzykantskaya sent an immediate reply protesting the decision on the grounds of the ‘patriotic attitude of the project and participation of artists from DNR and LNR’ (acronyms which stand for the Luhansk and Donetsk republics). ‘It will be the first exhibition at the State Tretyakov Gallery in which artists from LNR and DNR will take part. With all due respect, I am not sure you have the authority to make such decisions.’ Subsequently, Muzykantskaya herself showed both letters to the editorial team at Forbes Russia.

A few hours later, on the eve of national holidays in Russia, the Ministry of Culture took the decision not to open the 9th Moscow Biennale at the Tretyakov Gallery. In a press release sent to several selected journalists, the Ministry said that ‘the level of a number of works to be shown did not correspond with the status of the venue chosen for the Biennale, a state museum of federal importance’.

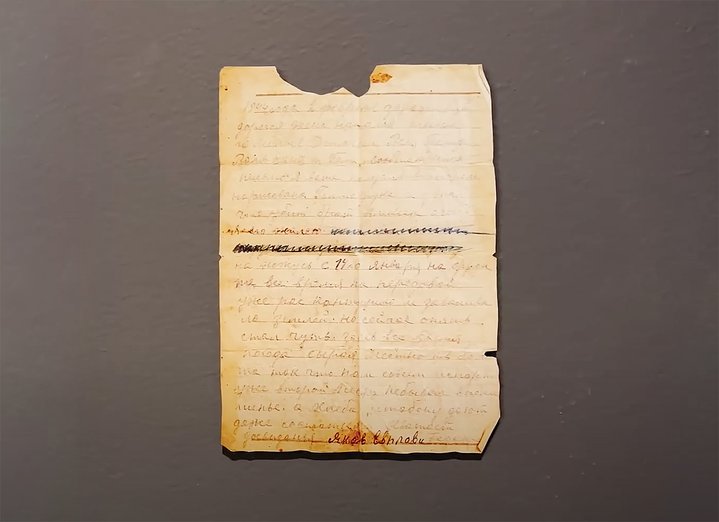

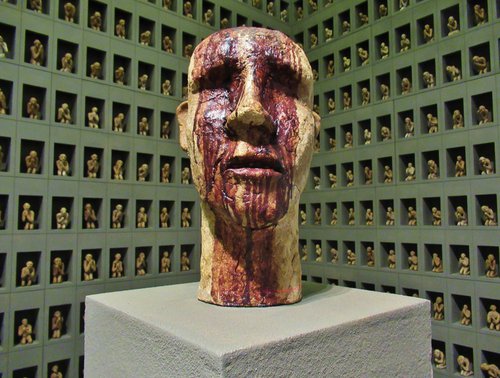

And so, from a dispute between economic entities, letters sent by the Biennale's management to Zelfira Tregulova, director of the Tretyakov Gallery, from 15th of September to 3rd of November, copies of which Musykantskaya forwarded to the media, talk about wires, emergency shutdown, fire evacuation plans and an electrical switchboard, the scandal surrounding the Biennale turned into a patriotic pogrom. On the morning of the 4th of November, the Biennale's PR people circulated a press release: ‘We were not given a chance. It's a pity that Moscow won't see works by artists from Donetsk and Luhansk. In her dedicated space, Nastia Deineka has recreated the ‘Angel of Donbass’ which she first painted on the wall of a bombed-out kindergarten on 1st of June, 2022. And we hung a video of her work on the walls of Donetsk next to it’. The organizers managed to make a video of the exhibition before it was dismantled and posted it online. It showed a curious mixture of familiar works by well-known artists such as Marina Belova (b. 1958) and Alexei Politov (b. 1966), Evgenia Buravleva (b. 1980) and Tatiana Badanina (b. 1955) with naïve ‘patriotic’ kitsch vibe.

The Tretyakov gallery’s press office only put out a public response on the 7th of November. The following message appeared in their Telegram channel: ‘At the request of the Tretyakov Gallery, the exhibits were removed for being incongruous with the status of the venue chosen for the biennale, the artistic and ethical context of the exhibition, and the stated age limit given by the organizers of ‘6+’. There have been no further communiqués from the museum as its director Zelfira Tregulova is on holiday until 12th of November.

On the morning of the 7th of November, the Ministry of Culture, and the senior management of the Tretyakov Gallery were hit with a blast of collective fury from the art community. 27 aggrieved artists who had been due to participate, and whose participation had still been under wraps, vented their frustrations and anger. Having shamefully disregarded all the standard rules for creating and publicizing large exhibitions, the 2022 Moscow Biennale had not announced the theme of the exhibition; they had not announced the names of any curators, nor the participants nor their projects. Artist Sergei Bugaev (b. 1966) who is known for a pro-government attitude and even once was a trusted representative of Vladimir Putin during a presidential election, said it was a matter for the upper political echelons. He said that it was time to appeal for help from the Deputy Head of the Security Council of the Russian Federation (and former President) Dmitry Medvedev and its Secretary Nikolai Patrushev, because as he said in an interview with Russian website Podyom, ‘there are tragic events in Russian culture: most of the institutions are run by liberals who have not produced a single exhibition in the last six months that would tell us where we are, how this has happened and with what it is all connected’.

As early as the 7th of November, Russian state-run news agency TASS reported Culture Minister Olga Lyubimova's reaction: ‘We believe the controversial exhibition is possible, but not at the Tretyakov Gallery.’

There had only been 27 artists due to participate in this 2022 Biennale and no parallel, or special, educational programme had been planned, nor guests or curators invited from abroad. The Moscow Biennale had long since begun to drift away from the big international exhibition it once was, when it warmly appealed to accommodate the maximum number of guests and participants, actively announcing itself to the world. Even back in 2015, the 6th Moscow International Biennale was held in a non-traditional lecture format in pavilions at the VDNKh, a historical exhibition complex in Moscow. The celebration of contemporary art has long been overshadowed by budgetary problems including because of sanctions imposed on Russia in 2014 and the physical fatigue of the Biennale's founder Joseph Backstein, who had headed it up since 2005.

In May 2016, Backstein had handed over the Moscow International Biennale of Contemporary Art brand to Yulia Muzykantskaya. Once conceived as a major international exhibition with the aim of helping to foster an interest in contemporary art culture within Russia, strengthening Moscow's status as one of the world's capitals of culture and a centre of attraction for the artistic community in Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union, the Far East and Central Asia, in 2015 the Biennale shifted to an educational format. And under the leadership of Muzykantskaya, who became president of the Biennale (Backstein had previously preferred to call his position using the conventional European terminology as ‘commissioner’), the Biennale had sunk towards total self-discredit in three editions since 2017, including the failed 9th Biennale.

From its position once as an independent international contemporary art organization in Russia, the Moscow Biennale has moved on to fulfilling social orders from the authorities, to showcase art that is servile and politically correct. Perhaps it was her proximity to the authorities and the attraction of administrative resources that Backstein liked in Muzykantskaya who he chose as his successor over several other potential candidates. Yulia played along with Joseph, and she even changed her surname from Zazulina to the surname of her adoptive father Alexander Muzykantsky, once prefect of the Central Administrative District of Moscow under Mayor Yuri Luzhkov. But this did nothing to protect her from organizational disorganization, bills not paid on time and numerous scandals with exhibition architects and employees. Most tragically of all, the Biennale itself has shrunk year by year until little if anything remains.

9th Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art