Chekhov’s Seagull Is Spreading Its Wings

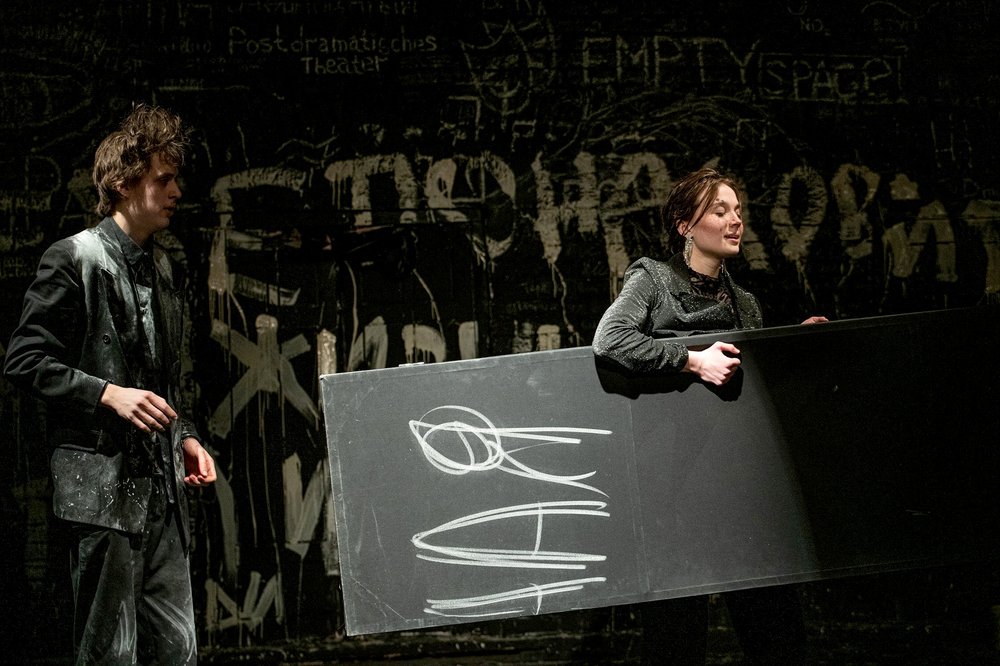

The Seagul. Based on the play by Anton Chekhov. Directed by Ilya Zaitsev. Photo by Olga Shvetsova. Courtesy of Yuri Butusov's Workshop at the Russian Theatre Arts Institute (GITIS)

Two productions of Anton Chekhov’s iconic play, omnipresent in Russian theatres today, shine a light on the problematic field of contemporary interpretations of the classics. Critic Sergey Khachaturov reflects on the phenomenon.

Written over a century ago in 1896, Anton Chekhov’s (1960–1904) world-famous play ‘The Seagull’, is in great demand in Russia today among directors of all generations. If you look at the playbills in Moscow and St. Petersburg, you can find myriad versions in dozens of theatres. Moscow has just staged premieres of ‘The Seagull’ staged by Konstantin Khabensky (b. 1972) in the Moscow Art Theatre and by Konstantin Bogomolov (b. 1975) in the Theatre on Malaya Bronnaya. Lev Dodin’s (b. 1944) production of ‘The Seagull’ is continuing to prove exceptionally popular with audiences in St. Petersburg where there is even a theatre called the ‘Treplev-Centre’, named after the protagonist in Chekhov's play.

So why are screaming birds flying in flocks in the salty air of the Russian theatre? I think there are numerous reasons. The first is that the textbook always saves the day in times of social stagnation. Evergreen themes can be like a universal pardon granted by ignorant, evil authorities. They reach the painful points of existence and yet are not censored (although according to the laws of dialectics, these same evergreen themes can become an excuse for the director's own lack of ideas).

Passive consumption of the familiar ‘staples of eternity’ is the second reason for the popularity of ‘Seagulls’. ‘The Seagull’ is a great brand, like the Nutcracker at Christmas and New Year. General themes about the suffering of young artists and the brutal nature of talent are always helpful for theatre bosses - you can put it on your playbill with the confidence that all performances will be sold out.

I think there is also a third reason for the popularity of ‘The Seagull’ and it is to do with the specifics of Anton Chekhov’s stage language. People remember ‘The Seagull’ best for its lines, but the thread of the narrative with a plot which slips away is difficult to grasp. The lack of a rigid narrative structure, the atmospheric flickering of words and ideas are very responsive to the contemporary aesthetics of performance, where spectators become a co-participants in the theatrical situation and are free to complete it and to speculate. It is not by chance that in 2018 Chekhov’s ‘The Seagull’ became the subject of an epic exhibition ‘Dress Rehearsal’ at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art. Using various objects crafted by contemporary artists, Ksenia Peretrukhina and her curatorial team organised installation-situations based on fragments of the play and its characters.

For me personally, the most beautiful ‘Seagulls’ today are those that can keep their balance while flying. Not to lose altitude, not to fall into puddles of banal truisms and clichés. At the same time, they should react sensitively to today’s agenda and possess the quality of intermediality.

This quality of intermediality – responsiveness to different types of play whether music, the visual arts or theatre is a key distinguishing factor in ‘The Seagull’, which flew out of the nest of Yuri Butusov’s (b. 1961) Workshop at the Russian Theatre Arts Institute (GITIS) in the summer of 2024 and now you can see it (although rarely) on the stage of the Konstantin Raikin High School of the Stage Arts.

Director Ilya Zaitsev (b. 2000) experimented with the theme of the young writer Konstantin Treplev who suffers from creative torment and misunderstanding. Ilya Zaitsev becomes Virgil through the ups and downs of staging The Seagull. When he first started work on the play, he rang Yuri Butusov and there was a deafening silence on the phone for fifteen minutes, he could not say a word, he simply did not know where to begin. Zaitsev’s version is like a surrealistic nervous dream of the director himself with a dynamic flow of images weirdly embodied by Chekhov’s characters, who turn into Zaitsev’s classmates along the way. And everyone’s life in the characters is marvellous: ghostly, simultaneously vivid and palpable. This ability of all the characters to flip their essence into an unprecedented underbelly is fascinating. In the play, usually representing the clumsy obliquity of life, here landowner Sorin played by Semyon Shestakov (b. 2000) suddenly dances ballet. And for him dance becomes a displaced creative essence. The young actress Nina Zarechnaya played by Evgenia Leonova, (b. 2001) sings the monologue given to her by Treplev in the spirit of folk song: strongly, beautifully and passionately. And Treplev, played by Daniil Yadchenko (b. 2000), is like a young Vsevolod Meyerhold. In his slightly comic, absurd suffering, he tries on different roles: either a street-artist, writing words from his monologues about the meaning of art on a fence, or he plays Ilya Zaitsev himself: shy, insecure, but dedicated to the theatre and Butusov, a director of various interesting predicaments. All in all, the play has a therapeutic effect and seems to be made on behalf of the absent Doctor Dorn, an alter ego of Anton Chekhov himself.

Dorn also disappeared in the version of ‘The Seagull’ created last year by the legendary Lev Dodin at the Maly Drama Theatre – the Theatre of Europe in St Petersburg. Lev Dodin has an exceptional talent for as well as experience in fostering a love for the classics among contemporary audiences, bringing them to life, engendering sympathy without breaking the original structure by the playwright, without replacing the text with topical pamphlet speeches (as Dmitry Krymov (b. 1954) did in ‘Kostik’, another version of ‘The Seagull’ at the Moscow’s Pushkin Theatre, a very topical and politicised production from 2021 that has since then gone off stage).

Lev Dodin approached Chekhov’s speech with care and so his characters are complex, voluminal and interesting, but he also still worked on the text. As if playing solitaire, he dealt out the lines of different characters – Treplev’s lines were given to Arkadina and vice versa. Some characters completely vanished from the stage, among them Doctor Dorn, a wise and ironic aesthete who is deeply concerned about the creative impulses of the young talents of Treplev and Zarechnaya. Dorn dissolved into the lines of other characters and because of this, everyone's speech became more significant and paradoxical. The verbal cascades, and duels attack the viewers, and do not let them relax. They break the usual lulling rhythm of predictable mise-en-scenes and worn-out phrases.

Actor Yevgeny Zaifried (b. 2000), who performs Treplev’s role, comments: “Dodin’s theatre feels time very sharply and responds to it. I know this sounds commonplace, but it is true. A contemporary notion of time has defined the expression, dynamics, incredible density and brevity. It is as if the performance begins with a deep inhalation, and the exhalation comes only when the lights are switched on again in the auditorium. But the performance itself is not a paused breath. It is out of breath, like time is today. The director's idea is very clear, but at the same time the artist feels freedom, like a marionette whose strings are suddenly cut off from the arms and legs and head, and it is as if he is acting on his own within this idea. That's why each performance is not like any other.”

Arkadina, a provincial hysterical diva played by Elizaveta Boyarskaya (b. 1985), turns out to be much more ruthless and evil than usual. Here she is cast as a predator who cannot forgive either the failures or successes of other people. Dodin gives her bitter and angry words that are not in the original play and the degree of estrangement with her son Treplev becomes catastrophic. Curiously, in one fragment her words are borrowed from another Chekhov play, ‘Three Sisters’. Unexpectedly, in front of her ex-lover, the slightly tired belletrist Trigorin played by Igor Chernevich, (b. 1966), Arkadina reveals her new romantic interest in officer Vershinin putting any possible liaison with Trigorin out of the picture. Igor Chernevich portrays an elderly fiction writer so obsessed with putting words together into entertaining stories it becomes a curse like a card game. He is tired, disillusioned and, at rock bottom, surprisingly tactless. After Treplev's suicide, Trigorin immediately takes note of the mise-en-scene and details of the tragedy and the reactions of those around him. Thus, his new plot for a short story is born.

The rigid expressive manner in which the characters deliver their lines is supported by unexpected musical fill-ins, with everyone performing urban romances in a circle. Word and text taste tart and sharp. They both attack and wound. Sorin, played by Sergei Kuryshev (b. 1963), is not the usual cowardly layabout but a dandy, a witty and wise man who loves life. He took in Dorn, many of his lines, and clearly appears as the alter ego of the ironic and sharp diagnostician of life Anton Chekhov. Nina Zarechnaya played by Anna Zavtur, (b. 1999) is far from the fragile transparent ethereal girl who matures towards the finale. She immediately shows herself to be a strong willed, worthy rival to Arkadina. Very exciting is their duel and rivalry, in the spirit of queens from Schiller's plays.

Konstantin Treplev, played by Yevgeny Zaifried, is spiritualised and beautiful as Pierrot from the Symbolist paintings. At the same time he is cruel and capricious. At Dodin's will he immediately enters into a duel with Arkadina's lover Trigorin. He does not hesitate to throw insults in his face, accusations of a smallish literary talent. In Chekhov's play Treplev caustically and angrily spoke of Trigorin behind his back. Treplev loves Zarechnaya, but he loves his text about the world soul and the circle of life given to her at the beginning of the play more. That is why at the end of the play, before his suicide, he pronounces it himself as a personally suffered revelation.

Yevgeny Zaifried comments: “It seems to me that in ´The Seagull´ everyone deceives themselves and no-one hears anyone else. Is Treplev talented or talentless? For me this is not the point. When Meyerhold appeared in this role, the reaction of the critics was that he was a complete idiot. But whatever the version – Treplev is trying to find himself, dreaming of a life that doesn't exist but is the only one he needs, and fails when the dream crashes into reality, where he has no place. He learns the truth about himself, that he ‘makes an impression and nothing else’, as Sorin will say about him. Treplev fails to cope with this truth and is doomed. And our production leads him rigidly along this path to the finale where it diagnoses his demise. After one of our rehearsals Lev Dodin said: ‘Now we've got the play that Kostya Treplev dreamed of staging’. Important words for me.”

An empty stage with mirrored walls and rocking boats designed by Alexander Borovsky, (b. 1960) turns out to be the best location for the incessant piques and jabs of words in the dank world of art, from which Love has left.

Lev Dodin's production is timely, when a true artist is almost always an outcast in society by the will of circumstances, obliged in spite of everything to resist the meanness of the world. His version of ‘The Seagull’ is about the balance between lies and truth, heroism and cowardice, revelation and routine in art in general and in the theatre above all. These polar notions sprout into each other in the play itself and in its long stage life, with different directors, in their struggle with the temptations of their own egos. The rocking boats on the lake during a storm are an accurate image of the artist's new place in the world. This image became the leitmotif of Dodin’s ‘The Seagull’.