Butusov’s Unflattering Portrait of the Art World

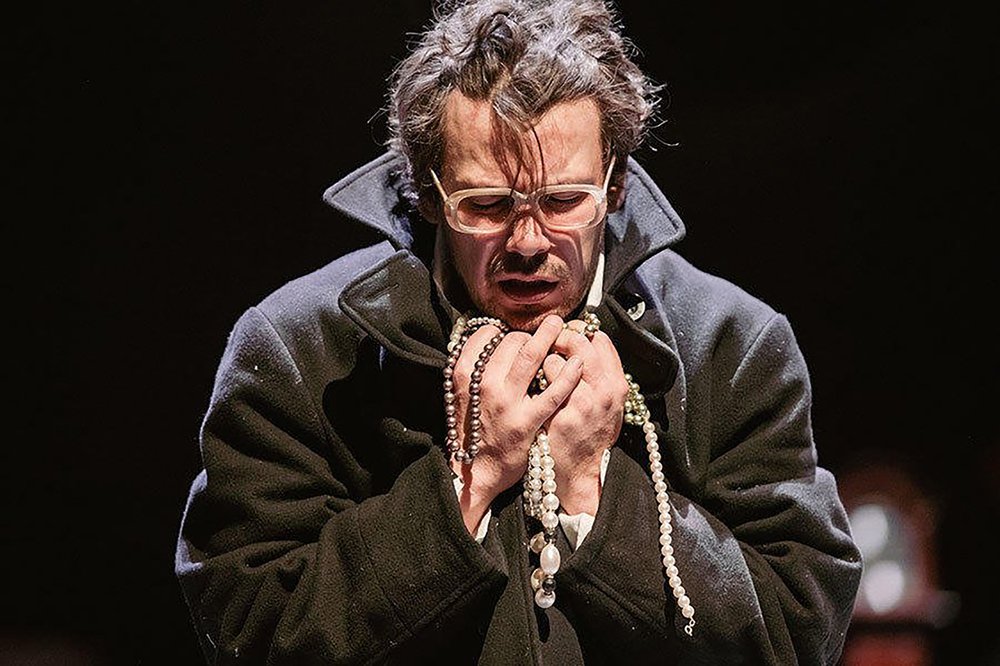

Gogol. The Portrait. Based on the short novel by Nikolay Gogol. Esther Bol (playwright) and Yuri Butusov (staging director). Riga, 2024. Photo by Kristaps Kalns. Courtesy of Mikhail Chekhov Riga Russian Theatre

Emigré director Yuri Butusov has staged an adaptation of Gogol’s surreal novella ‘Portrait’ at the Mikhail Chekhov Russian Theatre in Riga, a sobering take on the fate of an artist.

Director Yuri Butusov (b. 1961), who left Russia in 2022, has staged the great 19th century Russian writer Nikolai Gogol’s short novel ‘Portrait’ as a large-scale triptych about the nature of evil in art and the temptations of money and power. Working with playwright Esther Bol (formerly Asya Voloshina), the script has been peppered with numerous philosophical and diary observations by Vincent Van Gogh, Marcel Proust, George Orwell, Leonid Andreev and Andrei Bely, to create a large visual and textual collage, presented as a performance in which six actors play all the roles.

Shamil Khamatov, Mikhail Shiryaev, Dmitry Egorov, Volodimir Gorislavets, Alexander Malikov and Ekaterina Frolova all swap and switch between characters throughout the play. The protagonist himself, ambitious young artist Andrei Chartkov, who hankers after wealth and recognition, is portrayed by four actors in turn and at times even simultaneously. The production itself, with its masked role exchanges, its jagged rhythm and expressive, Brechtian montage of language about art and violence, evokes something of the dreamlike phantasmagoria of Francisco Goya’s etchings or Rene Magritte’s paintings.

This large-scale performance has a close point of reference in the ‘Monte di Pieta’ (‘Mountain of Piety’) exhibition curated by artist Christoph Büchel (b. 1966) at the Prada Foundation in the luxurious Palazzo Ca'Corner during this current Venice Biennale. The early 18th century Baroque Venetian palace has been transformed into an abandoned warehouse which houses a flea market. Everything on display has been discarded and stripped of ownership and biography. Usurious greed and the business of debt dominate. The original ‘Mountain of Piety’ was a pawnshop in Ca’Corner until 1969, which made loans to Venetians in exchange for their valuables. Later, the Venice Biennale archive moved into the palace until the Prada Foundation purchased the building in 2011. Browsing the mounds of vintage junk in such a luxurious palace brings on a feeling of discomfort or embarrassment as you come across stuff that has become hostage to usury. And there are also some genuine masterpieces, including works by Joseph Beuys and Andy Warhol serving as a reminder that the Palazzo Ca’Corner was until recently the Biennale’s storage space.

In short, art also features in a play about a world where debt speculation reigns supreme and harmony turns into chaos. Set designer Marius Nekrošius (b. 1976), son of legendary theatre director Eimuntas Nekrošius, has struck a similar note in Butusov´s production in Riga. He has turned the entire stage into a flea market, a dusty warehouse, replete with piles of rags, scattered antiques and frames. The palette is almost monochrome, the colours have faded, shrivelled.

Gogol’s story begins with an ambitious, 20-year-old painter called Andrei Chartkov who visits a junk shop where he comes across a terrifying portrait of a man with eyes that shine with a demonic force. It is the portrait of a moneylender, who offers loans in exchange for souls. Inside the picture frame itself, Chartkov finds a thousand gold coins. They help set him on the path to wealth and fame, a process that tragically ends up ruining both his talent and life.

Gogol’s account of how harmony can turn to chaos in the corrupt art world is emulated by both Büchel in the Prada exhibition and by the Butusov/Nekrošius stage designs for the Riga Chekhov Theatre production.

Similar analogies are evident in the installations of the Italian group Arte Povera whose members included Jannis Kounellis (1936–2017) and Michelangelo Pistoletto (b. 1933). The Arte Povera movement criticised capitalism, the narcissism of the artistic elite, their obsession with ‘the masterpiece’, which was to become the artistic scourge of suppression and humiliation. Thus, in the case of the Arte Povera artists, things thrown on the rubbish heap and rendered derelict become harsh witnesses testifying to the woes of civilisation and the subordination of art to the evil of the world.

Büchel's exhibition at the Prada Foundation resembles a colossal Arte Povera installation. This is no accident, given that until recently the left-wing philosopher and critic Germano Celant was the curator of the Prada Foundation. And the world of Butusov's ‘Portrait’ is assembled as if scripted according to Arte Povera installations. The characters sift through a huge mound of shabby rags. The portrait of the moneylender depicts a white field draped with a rope, with two black overcoats, apparently representing the giant eyes.

In the course of the Riga performance, this compost pit of civilisation, created in the spirit of arte povera, is filled with gruesome metaphors about the temptation of the artist who sees himself as a god. All the leitmotifs of Romantic literature, starting with the archetypal Faust, reinforce Butusov's idea: the lure of power turns the artist into a murderer of harmony. Blinded by ambition, he unleashes a war against nature and the world. Texts from different eras are intermingled and intertwined. They are juggled by the different actors in this three-part mural. Lofty words about the purpose of art deflate to become the same second-hand junk. They disintegrate into ashes.

Like the exhibition at the Prada Foundation, the theatre's account of the art world's transformation into a moneylender's shop in hell seems hauntingly relevant today, but the whimsical patterns of imagination that fill the strange hiding places and pockets of the theatre spaces help to sustain our spirit.