Brainwashing on Betancourt Street

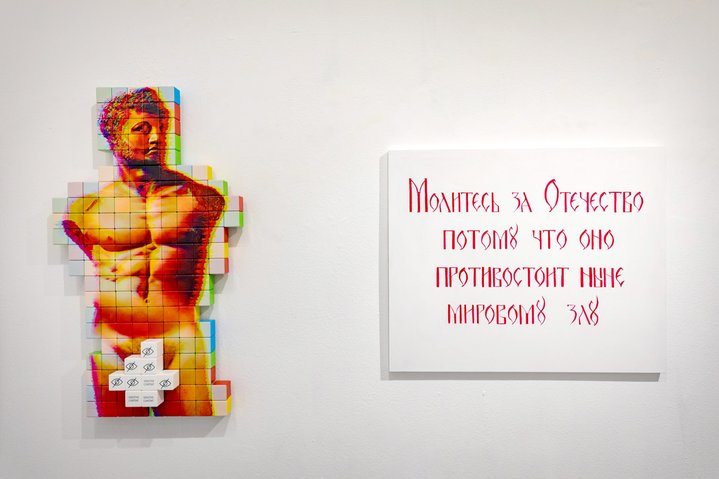

Art group Yav. Evolution, 2024. Courtesy of Brainwashing Machine project

With no real institutional platform at home or abroad, Russia’s radical contemporary artists are turning to small scale shows in less established venues. Currently on view at the Zona Gallery in Madrid, is ‘The Brainwashing Machine’ an act of political propaganda or a human story about resistance in the face of collective stupor?

Nowadays brainwashing seems to be everywhere in our progressive post-global world, and not just the product of totalitarian regimes. Brainwashing is not a new idea, notions around it became popular after the Second World War when the term was first used in the West, coinciding also with the publication of 1984, George Orwell’s classic novel about a dystopian society when the world was organised around two opposing imperialist camps: capitalism and communism. Looking over the fence, it was easy to see how people on the other side were being brainwashed, but now, forty years after Orwell, brainwashing in its many different guises has become one of the most insidious threats to our human survival. It is the subject of a new exhibition in Madrid called ‘The Brainwashing Machine’. A metaphor – or lesson – for any form of socio-political control, this show is about contemporary Russia, but it could just as well be about anywhere else.

Those behind both the Zona Gallery and the exhibition project prefer anonymity, there is no official curator of the exhibition which is a sign of the times and the content of the show. The gallery itself is surrounded by grand yet faceless state ministry buildings and only the street name stands out: Calle Augustin de Betancourt is named after one of the founders of modern engineering in Europe known later as the ´Russian Spaniard´. He became one of the most prominent engineers in early 19thcentury Imperial Russia, along with thousands of other specialists, imported from Western Europe to modernise Russia and carry on the legacy Peter the Great started of building a ´window on the west´.

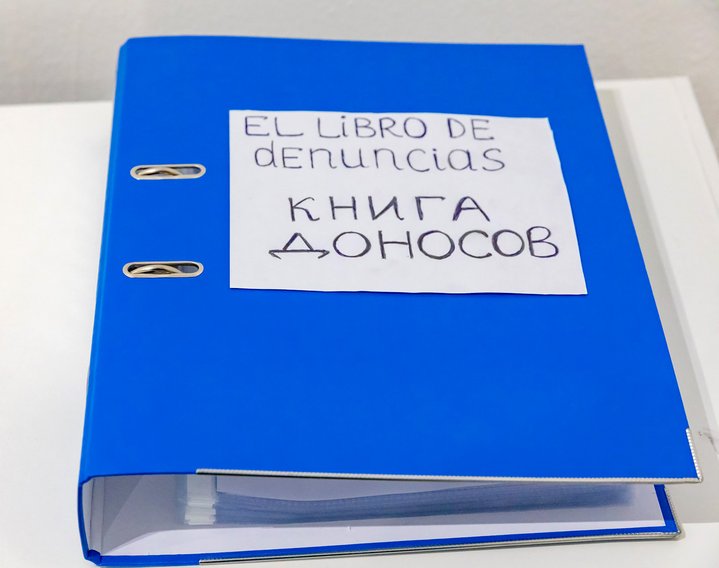

The Zona Gallery is mostly underground, consisting of a suite of badly lit, small rooms with freshly painted white walls and low ceilings, which you access down a narrow, steep staircase from a small entrance. At the door, a sign written in both Russian and Spanish welcomes you to the ´Brainwashing Machine´, after which you walk through a finely crafted narrative of how social and political brainwashing takes place, from the pre-wash to the main wash, to rinse and spin, metaphors mix with well-researched facts chronicling key events defining present-day Russian social policies and their consequences. The familiar sounds of a real washing machine resting and rinsing come from a speaker sitting on the floor behind a gigantic eye which looks up at you.

The concept of social and political brainwashing emerged in the 1950s when the word was first used by an American journalist Edward Hunter, to describe Mao´s China. He translated it directly from the Chinese language ´Xi Nao´ to describe the practice of cleansing your soul before going into a holy place, a great irony lost on our contemporary understanding of the word. As humans we are incredibly powerful and yet our weakness is that, as social beings, we are hard wired to act like herd animals. It has enabled humans to garner huge communities of people to fight for one cause, and achieve progress, yet the cost is that we can all turn into mindless slaves. Whether it is Social Media Inc. or the self-absorbed rantings of despotic leaders in authoritarian regimes filling us with hate, we have our blind spots. Several of the works on view play on vision and our ability not to see things as they are, from artist Valentina Sergeeva´s black and white Op Art prints in which the words ´My Opinion´ fade into the design and become hard to read, to a mock Optometrist’s chart with the word ´Fear´ spelled out in the characteristic large letters on the top line, ending with the words ´peace and love´ on the bottom line, printed so small that they are hardly visible at all.

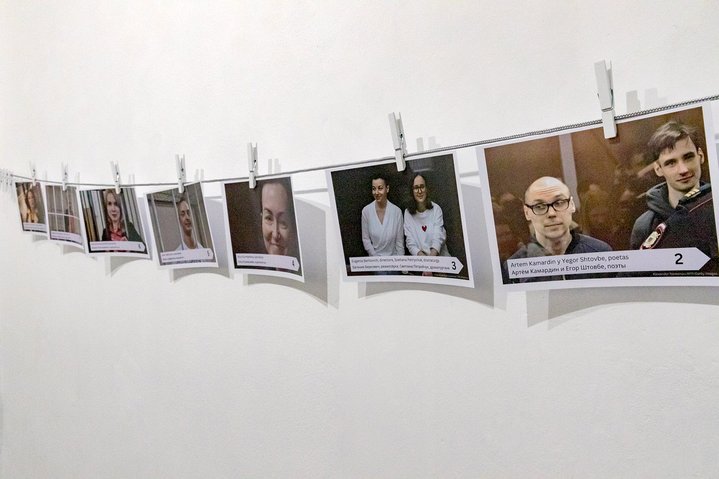

Since the invasion in Ukraine, contemporary artists in Russia have become increasingly fearful of persecution by the authorities, in a climate which tolerates no dissent – in times of war everything acquires an urgency, there is no compromising, there is one official message and everyone has to follow it. This, as well as the threat of mobilisation, has forced many artists abroad, creating new émigré circles, most of which are in Western Europe and are becoming increasingly active, conscious of a rich trove of historical precedents before them. Writer Maxim Gorky famously spent seven years living on the island of Capri writing about his homeland, in part to distance himself from the repressive atmosphere in Russia in the years before the Revolution. In New York, émigré dissident artists created a kind of scene in the 1980s, and more recently, an exhibition in Paris last December brought together two generations of émigré artists, creating interesting new perspectives. But in the current tense climate, even in the West, Russian contemporary artists have little leverage, and after a decade of numerous Russian themed exhibitions in major Western cultural institutions (albeit mostly focussed on the historical Avant-Garde), support has now vanished.

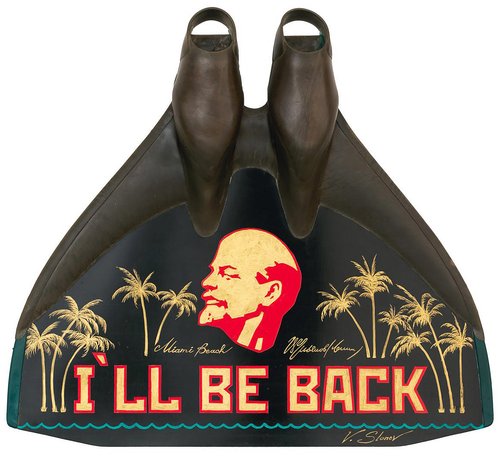

Back in Betancourt Street, in one of the central rooms of the show called the centrifuge, Russian artist Pavel Otdelnov (b.1979) questions the popularity of autocracy and why it is that as people we need to place our faith in a figurehead, even if this is often tragically misguided. His painting Ábyss Shadow´ depicts the tens of thousands of mourners who attended Stalin´s funeral in 1953, in the artist´s imagination their grey indistinguishable faces create a mass of people under a black hole in the sky, which casts a long shadow… His other work in the show is kind of readymade piece, an Eastern style rug like the ones which used to hang on the wall above a divan in every Soviet home, only this one is painted with tiny soldiers carrying rifles hidden among the elaborate oriental scrolls. Along with Otdelnov, Slava Ptrk (b.1990) and art group Yav, are all leading contemporary artists from Russia included in the show, together with a roster of international names. Thai painter Vasan Sitthiket (b.1959) whose body of work consists of repeated self-portraits in which he debunks state authority in Thailand, here is represented by a painting called ´Fake News´, a fitting byline for our times. British ceramicist Sophie Woodrow (b.1979) has made a series of small porcelain figures called Whorls, like spinning tops that have many faces when at rest, and yet, when they are spun around, they appear to have only one face.

Finally, in the last room of the brainwashing machine, the tumble dryer, you are confronted with a large, red blow-up mannequin like the ones people take on political marches or protests in public, but this one is sitting on the floor in a cage. Beside it there is a white door with a quote by Alexey Navalny, written in Russian with a black marker pen: ´I´m not scared and you´re not scared´. This work is by an anonymous group, and simply called ´Exit´.

Like Woodrow´s porcelain whorls which do not sit still even when at rest, our world is inherently unstable, and ever the optimist, I think that this can bring hope for change. Despite all of his achievements, the once unstoppable Augustin de Betancourt eventually fell out of favour at the Russian Imperial court and lost his job as director of Communications. An ambitious and talented man who was accustomed to doing great things on a grand scale, I am not sure what he would have thought of this small, dystopian lament about the state of affairs in his adopted homeland in a tiny, low-tech, underground gallery in his street. I like to think that he would have got the message - while he marvelled over the electric washing machine, such a great invention.