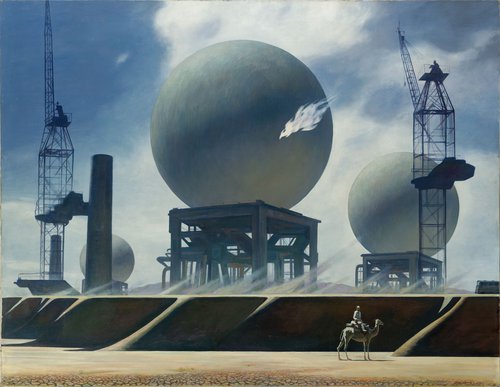

Aleksandr Deineka. At the Women’s Meeting, 1937. Chelyabinsk State Museum of Fine Arts. Courtesy of ARS/UPRAVIS, 2022

Beyond Propaganda: Deineka and Socialist Realism

A new book about Aleksandr Deineka by American academic Christina Kiaer challenges the relationship between the Russian avant-garde and Socialist Realism. Looking at broad movements and contexts Kiaer redefines the narrative about how Socialist Realism intersects with discourses on contemporary art.

In her new book ‘Collective Body: Aleksandr Deineka at the Limit of Socialist Realism’, American art historian Christina Kiaer fills a distinct gap in traditional histories of Socialist realist aesthetics. Kiaer disagrees with the existing theory that the Russian avant-garde and Socialist Realism were working towards different aims. Moreover, she challenges the notion of Socialist Realism as a purely state-led or state-influenced initiative. In her book she fuses events often understood individually on an intuitive level to arrive at far-reaching connections such as those she observes between Aleksandr Deineka (1899–1969) and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973).

In her preface, the author describes how Deineka’s work has even been used for nationalistic purposes in contemporary Russia to bolster internal support for its occupation and invasion of Ukraine. Kiaer calls for an historical re-reading of Deineka’s work in order to regain the original context in which he produced his work.

Kiaer disagrees with Benjamin Buchloh’s argument that propaganda is not art. She maintains that propaganda had no such negative connotations in Deineka’s time, in fact she argues that propaganda art was perceived positively, equating it with socially engaged art of today. She reviews the context in which the work was made and deliberately eschews the use of contemporary codes and structures in her analysis. She also disagrees with the theory espoused in Boris Groys’ influential book ‘Gesamtkunstwerk Stalin’ that ascribes sole authorship of the Socialist Realist project to Joseph Stalin. In Kiaer’s view, it was the artists who largely formed, developed, and contributed to the system that propped up and emboldened Socialist Realism.

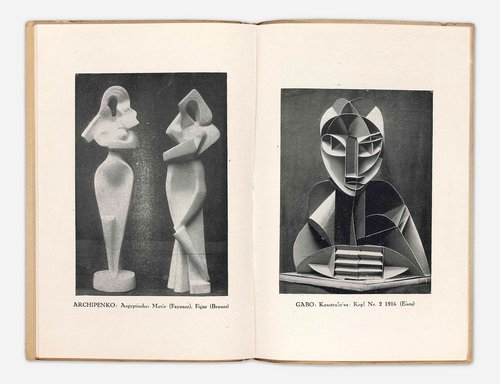

Despite Groys’s call that historians should devote more attention and recognition to Socialist Realism, the style remains understudied today, with a strong preference for the Soviet avant-garde which came before it. The dominant historical view is that the two styles represented opposition movements, an interpretation Kiaer insists is wrong. Instead, she brings the two together in a dialogue that yields new and interesting ideas.

Ultimately, Kiaer’s argument is for a collective reading of Deineka’s work, linking his artworks with the avant-garde in their ability to activate and inspire collective action. An underlying thread running through her book is a feminist interpretation of Deineka’s portrayal of women. Kiaer justifies her decision to write what amounts to a monograph by stating that “a single artist study can counter the perception of Socialist Realism as a monolithic or totalitarian system that enforced conformity to ideological content and a universal style”. Such a fresh approach is indisputably the strength of this book. The focus on Deineka allows the reader to zoom in and out of a nuanced historical context. Additionally, the author’s reliance on the use of the “forcefield”, or lived experience, contributes greatly to the success of the monograph, since she turns her focus to the artist’s on-the-ground concerns and activities and the art ecosystem surrounding him.

‘Collective Body’ is divided into seven chapters, the first of which describes how Deineka developed a sign system that was used to define the proletariat. Of particular value in this chapter is Kiaer’s account of slippages that often occur in the academic space between departments. In chapter two, the author argues that the monumental paintings Deineka created between 1925 and 1928 were a direct challenge to Constructivist claims that painting was a retrograde, bourgeois medium and therefore unsuited to Socialist art. Chapter three describes Deineka’s participation in the ‘October’ avant-garde group, and how he worked both within and against the avant-garde. Chapter four turns to growing critical concerns about the depiction of emotions, something that was to become a major preoccupation of Socialist Realism, as reflected in Deineka’s large-scale ‘lyrical’ paintings.

Chapter five focuses on how Deineka portrayed race, sexual commodification, and boredom in American capitalist society and how Soviet critics responded, demonstrating how the development of Socialist Realism, far from being a linear progression, was ultimately the outcome of explorations conducted down multiple avenues. Chapter six examines the Terror through two ‘primal’ paintings, the commissioned ‘Illustrious People of the Land of the Soviets’ and ‘At the Women’s Meeting’, placing both within the context in which they were exhibited. The final chapter considers Deineka’s revival following a hiatus arising from accusations of formalism. Here, Kiaer describes how the artist’s work served as a local counterforce to the popular 1956 Pablo Picasso exhibition.

By using a monographic format, Kiaer’s description of Deineka’s invention of the proletarian body in chapter one necessarily focuses too closely on the artist, overstating a claim that he was solely responsible for the signs used to represent the proletariat and this issue runs through the book. She is at her strongest when using the ‘forcefield’ approach and incorporates evidence from Deineka’s broader social sphere.

Kiaer is a wonderful and engaging writer, and her description and analysis of the works demonstrate her aptitude for detail and only in some instances is there a need for greater clarity. For example, her use of terminology can be confusing at times. Although the reader is able to discern meaning through context, sometimes a brief explanation would have been of benefit.

‘Collective Body’ demonstrates how Deineka’s work, and Socialist Realism more broadly, can be seen as converging and diverging crucially with the avant-garde, suggesting that his work can be read as an alternative to avant-garde modernism and thus should be interpreted alongside it rather than in opposition. Kiaer’s significant contribution opens up exciting new paths for scholarship on Socialist Realism. Although the book traces the development of Deineka’s work in an accessible way, ‘Collective Body’ may be best suited for those familiar with the discourse on the avant-garde and Socialist Realism as the uninitiated reader may find themselves missing out on some context.

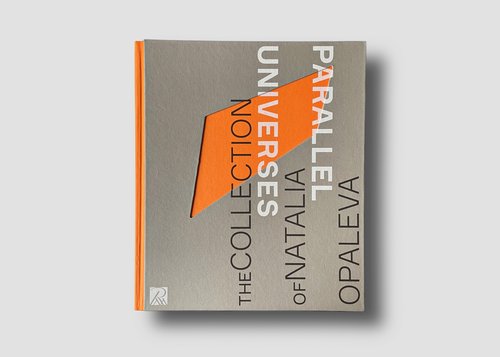

Christina Kiaer. ‘Collective Body: Aleksandr Deineka at the Limit of Socialist Realism’

Christina Kiaer. ‘Collective Body: Aleksandr Deineka at the Limit of Socialist Realism’