Between Scorn and Soirée: Slavs and Tatars at Artwin

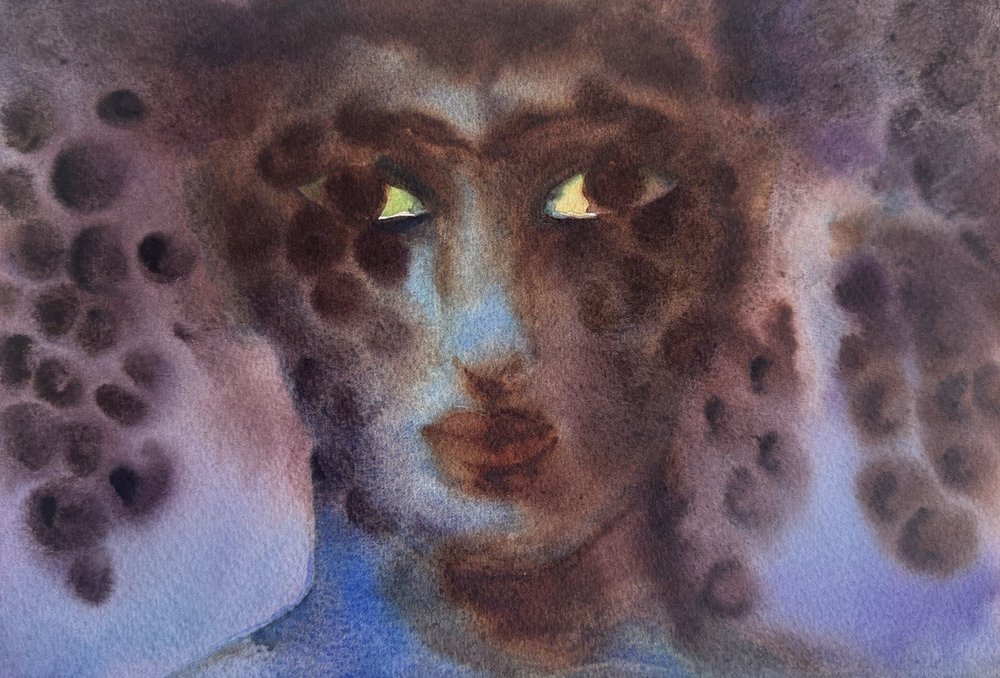

Akhmat Bikanov. Untitled, 2024. Courtesy of Artwin Gallery

The current exhibition at Artwin in London, ‘To Everything spurn, spurn, spurn’ is vividly illuminated for Art Focus Now by the boisterous yet dark British humour of art critic and writer Alistair Hicks, for whom the whole shebang takes the turn of a 20th century cocktail party in the English shires.

A hostess, both proud and anxious that she had managed to attract Oscar Wilde to her Soirée, approached him and said, ‘Oscar, I am glad to see you are enjoying yourself.’ ‘It is lucky,’ he replied, ‘as there is nothing else to enjoy.’

It seems that the curators Slavs and Tatars and Asya Yaghmurian have selected their eight artists for this art exhibition much as old-fashioned ladies from the shires might have done for a drinks party. Geography here is the main thing, though Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and the stans are more unusual fodder to a cosmopolitan London audience than Burford and Cheltenham. Yet the principle is similar. The S&Ts have set about inviting their neighbours or at least the ones who are ‘socially acceptable’ with a couple of ingénues thrown in as one does to show how open-minded ‘one is.’ It is worth going as there are couple of real hits in this show, which for me made up for that feeling of trespassing in someone else’s drawing room.

The ‘party’ was presided over by Payam Sharifi one of the founders of Slavs and Tatars. Oscar Wilde would have approved of his aesthete’s attire – exceptionally elegant. Edward Said [ed. Influential Palestinian-American scholar and writer who argued that Western scholarship depicts the East through stereotypes serving imperial power] would not let me say Sharifi was dressed as Alladin, but maybe that is one of the serious points of this show. Westerners still tend to treat the ‘exotic’ as some kind of pantomime. The main subject of this show is scorn and disdain, but this exhibition is aimed at the British, like me, who if they have anything serious to say dress it up as a joke.

For those not as witty or brilliant as Wilde, nerves at 20th century cocktail parties sometimes do induce the most terrible name-dropping. Julian Miller, the brother of Jonathan Miller of Beyond the Fringe fame, left his London home for a weekend in the Cotswolds and went to one of those social occasions thrown by a local Lady of the Wolds. Armed with a Gin and Tonic he was making small talk when he made the mistake of asking his inquisitor:

‘Are you from London too?’

‘No,’ the man spluttered. ‘We have been here for four hundred years.’

‘Settling in well?’ responded Julian and rode off into the sunset.

Walking into the upper rooms at 9 Cork Street the first painting that engages the unbriefed visitor is ‘Experience of the inevitability of evil’ by Shamil Shaaev. It is cleverly presented. There is no frame, but two kitchen knives stick out from sides at the top. The whole wall is covered with Saule Dyussenbina’s ‘Athletic ornament (Kazakh Funny Games)’, which takes the form of wallpaper with a repeating pattern of couples knocking heads and horns with each other. The Kazakhs are carrying rams on their shoulders. Now to his painting of two heads, or rather one and an eighth heads. We only get a slither of the left-hand figure, but enough to see that both her/his eye white is not white but yellowing. This deadly tone is the only colour in the picture. It is present in both eyes we can see, one for each figure.

Shamil Shaaev’s portrait has more than a faint echo of Piero della Francesca’s double-portrait of ‘Battista Sforza and Federico da Montefeltro, the Duke and Duchess of Urbino’, 1416/17. The right-hand figure is facing two ways. The majority is in profile, but the mouth is twisted around towards us, as if it is telling us some malicious gossip.

Without any formal introductions to the guests/pictures at this party/exhibition I had to work hard to enjoy myself. I started making outrageous connections. The next-door painting to Old Twisted-Tongue Evil Eyes is not so exciting. ‘Looking for a look’ is a double-sided painting, and that seems about its only merit. Was it just made to fit in with the two-faced theme? I go back into the first room and am cornered by the one lonely old codger, a double-sided painting by an avant-garde painter who suffered the ironic fate of being declared a counter-revolutionary. Its front side is ‘Uzbek Children in a Yurt’, the reverse has a tag revealing that it came up at auction as Lot 20 in MacDougall’s sale of 30thNovember 2016, valued at £150,000–200,000.

The brightest things in the first room are in ‘Slavs and Tatars’ light installation, ‘Dark Yelblow’. I got out of my corner to ask Aladdin to interpret his lamps, and he did a brilliant job in explaining his magic. Before Sharifi had spoken I had seen the installation as decoration. The glass lamps were sub-Liberty’s. But his magical words turned the lamps into watermelons. Over and above the cultural significance of watermelons in Uzbekistan and the region, he claimed they are found primarily on the margins, in parts of the world that have been marginalised. He uses the melons to show the complicated relationship between text and image in this part of the world.

S&T’s lights are like over-ripe fruit bursting at the seams. These seams are depicted by a blur of three scripts: Arabic, Latin and Cyrillic. We often think of language as tying concepts down, describing what we are, but language is always changing, as fluid as the ideas and systems we try to capture. Using the scripts from composite language Slavs and Tatars reveal our culture as oozing lava, energetic constant change.

I did get an invite to the opening, but I still felt a bit of a gate crasher walking up those stairs to Artwin, London, so to ease my social inadequacy I will conclude with some utterly shameless name dropping. In the mid-1980s I visited a hospital to see a friend, the writer and editor Mario Amaya, who was dying of Aids. He was most famous for being wounded when Valerie Solanos shot Andy Warhol in 1968. He loved gossip and the twisted double-sidedness of life, so I told him about a visit I had just made to interview Harold Acton in Villa La Pietra in Florence. I concluded the interview with a confession that Violet Trefusis was a cousin of mine. Nancy Mitford and he had written many vitriolic letters to each other about Violet. Acton paled and pointed at the Louis Quinze armchair I was sitting in.

‘I leant that chair to your Cousin and had to buy it back at the sale after her Death.’

Amaya was thrilled and responded with an even better story about scorn, disdain and Trefusis. On his first visit as a young Canadian to Paris, he gate-crashed one of Trefusis’ parties. After a while she swept up to him and said,

‘I gather you are an absolute non-entity and have not even written a book yet.’

Incidentally, he went on to write many books including one on Tiffany Glass.

Cocktail parties may be mainly dull, but I am very glad I went sp… sp… spurning with the elegant, funny Slavs and Tatars…