Bella Levikova: The Forgotten Voice of Soviet Nonconformist Art

Bella Levikova. Superposition – Physical World and Quantum World. Courtesy of Sistema Gallery

The Sistema Gallery in Moscow presents ‘Distances Marked by Strength’, featuring over twenty works by Bella Levikova. The exhibition showcases vibrant, semi-abstract paintings, bringing into the limelight an artist whose name was almost forgotten for several decades.

‘Distances Marked by Strength’ a solo show by Bella Levikova (b. 1939) is on display at Moscow’s Sistema gallery this winter. The exhibition includes over twenty canvasses mostly created by the artist over the past two decades. These brightly coloured, semi-abstract canvases appear rather unexpected against the backdrop of what galleries typically show these days.

The first painting that Mikhail Alshibaya, a legendary Russian collector of unofficial art who passed away recently, purchased for his collection (previously he had been gifted works) belonged to Levikova. This artist had entered the grand history of art back in the 1970s when she showed works at the exhibition hall of the City Committee of Graphic Artists, the only place in Soviet capital where ‘unofficial’ artists were allowed to show their work legally. In 1988, at Sotheby's auction in Moscow, her work was included in the catalogue alongside other prominent nonconformists. Like many of her contemporaries and acquaintances, she ended up in museum collections dedicated to underground art of the Soviet times. According to the gallery’s press release, her works are in the collections of the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, the State Russian Museum, the New Museum in St Petersburg, the Dodge Collection at the Zimmerli Museum in New Jersey among many others.

In spite of this, when art historians talk about the 1970s and 1980s, Levikova is rarely mentioned. Her name disappeared from the Russian art historical mainstream some time ago. And by and large, it has never properly returned, even though over the past decade the domestic Russian art scene has been retrieving forgotten names from obscurity, reconsidering attitudes towards the undervalued, and restoring the status of those excluded in one way or another. Levikova’s works have, of course, circulated through auctions over the past two decades, exhibitions have been organized in galleries, and albums with her works have been published. But globally, this has played no significant role. However, the very same process has occurred with a significant number of artists of her generation, as well as those slightly older and slightly younger. Let us attempt to describe it.

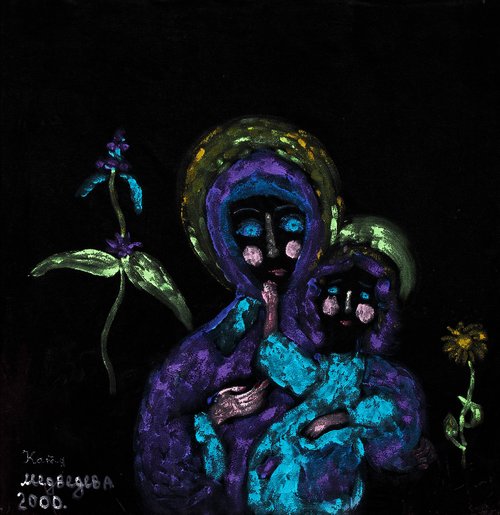

Surveying Levikova’s works, the first thing that strikes one is that they are all reminiscent of something. Nothing specific, more a composite of multiple familiar motifs. There seem to be references to Fernand Léger (1881–1955), Roberto Matta (1911–2002), Vladimir Yankilevsky (1938–2018), Victor Pivovarov (b. 1937), and many others. And simultaneously, it is easy to imagine how Levikova’s paintings, under the influence of some remarkable occurrence, could mutate and transform with ease into works by Gosha Ostretsov (b. 1967), Oleg Kotelnikov (b. 1958), and later artists existing on the border of kitsch, pop art, and wild abstraction. That is, the artist literally freezes on a line of contact with on one side the avant-garde and artistic underground of the Soviet Union and on the other artists who came onto the scene from the mid-1980s onwards. It turns out that although Levikova has a bit of everything, regardless of what it was that she herself invented and what she borrowed, all of it has already been credited to someone else. As in the case of hundreds of her contemporaries, at the moment of the canonization of unofficial art and its transition into the state of post-Soviet contemporary art, the artist did not find herself among any dominant group that had crystallized back in Soviet times or was newly formed.

Another important factor that has massively influenced Levikova’s falling out of the mainstream was her fascination, if not obsession, with quantum theory, astrophysics, genetics – naturally, not in a scientific vein, but in the spirit of artistic reworking. Moreover, psychology, philosophy, and esotericism were added to this. One must understand that even in the Soviet underground, the conceptualists, who began to subordinate the interpretational toolkit of art to themselves, harshly cut off any attempts at ‘becoming stuck’: in their image of the world there should be nothing that would transcend the very matter of the artistic, that would define it from outside. They started by defeating the ‘metaphysicians’ – those who advocated for the primacy of the spiritual and achieved this so successfully that many of the vanquished renounced their own views, whilst art critics forgot about others and only appreciated them properly in the mid-2010s (though now the imbalance has swung in the opposite direction).

A similar displacement affected those who proceeded from some pseudo- or quasi-scientific theory. Thus, Yuri Zlotnikov (1930–2016) in this regard was recognized as an artist with a strong sense of forms, but simultaneously – as a dangerous marginal with harebrained ideas. Coupled with his explosive character, this led to serious complications in his creative path. Therefore, the figure of Levikova, who, incidentally, saw in Zlotnikov a kindred spirit, also became very marginalized on account of her fascination – completely without any irony or distance – with pseudo-science and vague spirituality. Now all these things are considered fashionable in the art world, but back then the artist found herself out of favour with her interests – and missed her chance.

The Sistema gallery exhibition reveals how Levikova works in one large series. Thus, in paintings created in different years, the phrases ‘Co-existence of Con-sciousness’ (variant ‘Event of Consciousness’) and ‘Philosophy of the Moment’ repeatedly surface in the titles. And there are two canvases hanging side by side, which are named in such a way that they seemingly shouldn’t belong to the same universe, which were created with an 18-year gap (‘The Sower’, 2018, and ‘Superposition – Physical World and Quantum’, 2000), and are so close that one understands her work as one large puzzle, the fragments of which are methodically laid down year after year, so that ultimately one large picture emerges – in the spirit of the artist’s syncretic worldview, where quantum physics meets esotericism. In this sense, if one were to fantasize, it would probably be logical to show Levikova’s works in large volumes, crowded together, literally hanging from above the viewers from all surfaces. Then the intention of the artist – to tell the truth, however she might understand it – would be realized to some degree. For now, however, she is far from this.