At pop/off/art Potapov Goes Black and White

In Moscow a local artist has sparked controversy by turning the inside of an art gallery into ruins as part of a solo show which addresses the timely themes of destruction and denial.

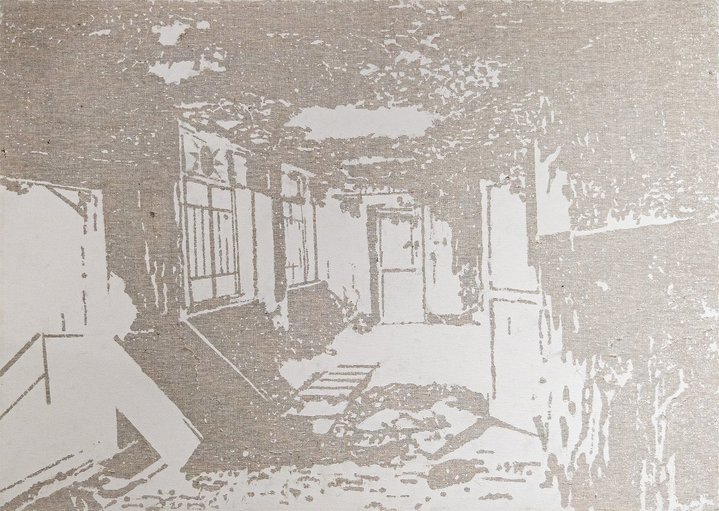

There are more chances of seeing a white elephant in Moscow than an art exhibition which addresses head on the nation’s current affairs. But Vladimir Potapov’s (b.1980) solo show at pop/off/art gallery does just that. Don’t expect it to be pretty. The gallery space has been trashed; visitors encounter works of art which remain intact amongst smashed plasterboard walls; the floor is covered with debris. And just before it opened, the gallery posted a video on social media of the artist ecstatically destroying the walls with a hammer. Hanging in the gaps which remain after this burst of creative destruction are large canvases with images of ruined buildings. They have not been painted but the coat of white ground that covers the canvas has been scratched in. One can term it painting in reverse or negative painting.

These works, together called the White Series, are almost all based on real photographs taken from the mass media. Born in Volgograd, Potapov has now been living in Moscow for many years and is known for his – usually – colourful, engaging works made using complex techniques he pioneers himself. For his series called ‘Inside,’ he covered canvases with 15-16 layers of paint, revealing hidden layers by scratching images into the surface. The White Series was born out of this earlier project. It was during the pandemic in 2021 that the artist created his first white work, at the time a one off as he did not see a way to develop it further. However, he returned to it a year later, after the armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine broke out. As he puts it: “I don’t know how to work with colour now, I feel an inner aversion to it.”

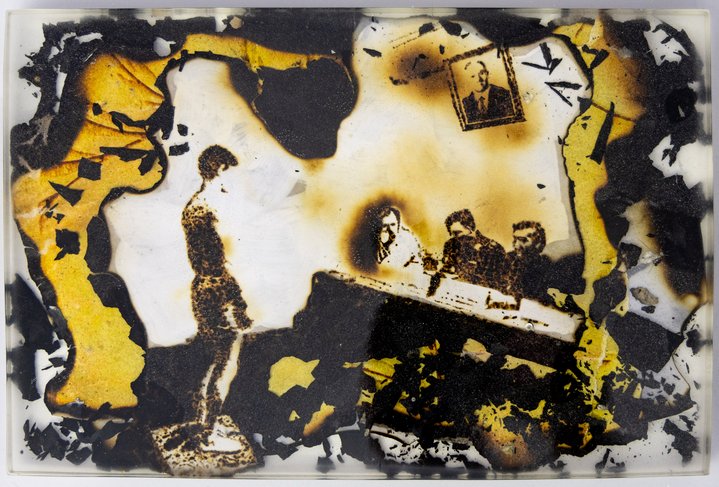

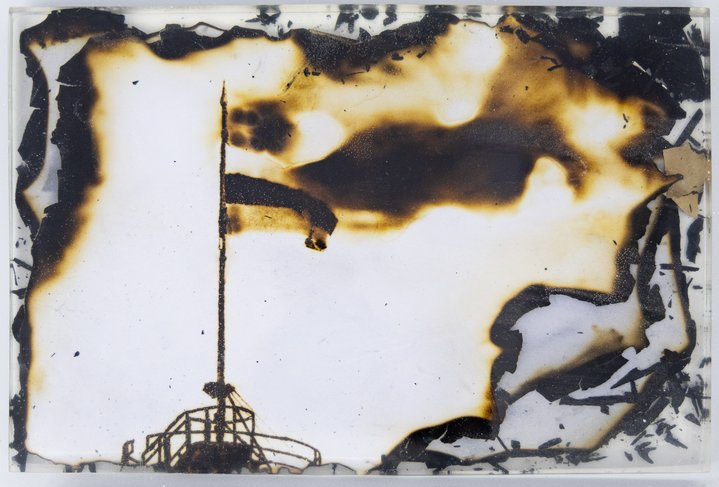

For his Black Series, also on show at pop/off/art gallery, he uses a different technique in which black images on paper are created by fire. These ‘drawings’ are then covered with epoxide resin to make them glossy and to help preserve them. The title of the exhibition, ‘Both Are White’, alludes to a 1970s Soviet documentary ‘Me and the Others’ which told the story of a shocking psychological experiment. Children were shown two toy pyramids, one black and the other white. Among the children there was one child who was the unsuspecting subject of the experiment, the rest actors who answered according to a script. When asked about the colour of the pyramids the actors unanimously replied, “Both are white”. The child who was being tested was the last to answer and repeated the same words, afraid to stand out from the rest of the group. The experiment was repeated on adults with the same result. “That’s how the system in the Soviet Union worked”, observes Potapov who feels that in Russia today things are similar. “People are forced to call the black white and the white black. They do this because they are afraid to tell the truth. They are afraid for their own lives and the lives of their relatives.” It is reflected also in the art scene. “In the art world people walk around with their eyes shut tight pretending they can't see anything”.

On social media Potapov’s project has sparked controversy. Some artists now living outside Russia have accused him of “aestheticisation of violence and the exploitation of suffering” as well as “appropriation of a tragedy”. When asked about this, Potapov is bitter: “I don’t think that this exhibition is ‘beautiful’ or can be seen as an act of aestheticisation. For me this is an exhibition that shows the horror and tragedy of what is happening.” He stressed the fact that the majority of critical comments were coming from those who are living abroad. “We are here in Russia, and we are taking risks”. He tells me that on the opening night four people came up to him offering to connect him with a good lawyer. “Everybody said the exhibition might be closed down and I could be arrested”. There are others who have taken his side. “Even artistic statements which can invite fair criticism are far better than ignoring what is really going on,” wrote Pavel Otdelnov (b. 1979), while Roman Sakin (b. 1976) reflects, “Is there a new rule now for Russian artists that you can only paint a destroyed house if you were in it and survived?”. Sakin added that “Just now Anselm Kiefer filled a gallery in London with concrete ruins, aestheticising it all over the place, and no one has criticised him.” When I asked Potapov himself what message he tried to convey to the audience, his answer was: “I want people who are afraid to speak out, to see that it is possible and must be done, and that there is no need to be afraid!”