Artists Exiled in Paris on their Experiences of Censorship

Thoe Htein. My life in pale, 2023. Courtesy of the artist

An exhibition at the Poush art cluster in Paris features works by exiled artists exploring the effects of censorship on identity and artistic expression. With an impressive array of powerful and distinctive voices from different countries, the show examines the unique struggles of creatives displaced by authoritarianism, war, and societal repression.

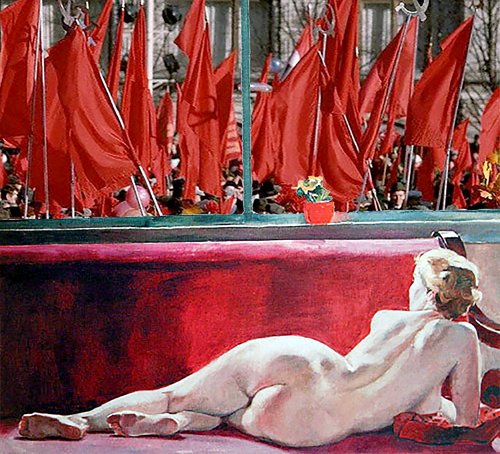

Poush, an art cluster in Paris is presenting ‘Censorship’ a timely exhibition that challenges the respectable bourgeois contemporary art fairs like Frieze London and Art Basel Paris. At Poush works by artists in exile from different countries around the world have been brought together - it is perhaps a fitting venue as artists in Paris have traditionally occupied a refugee niche, just like in the days of Modigliani and Chagall's Montmartre and it seems nothing has changed. Artists from across Ukraine, Russia, Africa, Palestine, China, Iran and Algeria once subjected to censorship in their home countries, whose work is shown in the exhibition, are most often people with broken biographies and wounded psyches. They are victims. Countries drawn into bloody confrontation devour their children like Chronos in the paintings of Rubens and Goya. If the cause of exile is not war, it is often authoritarian politics. The denial of human rights, dominant authority figures, the gaslighting of minorities, the repression of minorities, are all atavisms of dictatorships and decaying empires in the East and Africa. But for the artists, their adaptation to a new life in Paris, or in other Western European cities does not come without pain and is fraught with the threat of losing their own identity.

The Agency of Artist in Exile (L’atelier des artistes en exil) has its own dedicated space in Poush. All of the above complex contradictions define many of the problems that artists in the Atelier face on a daily basis. The staging of an exhibition about censorship is interesting in itself. There is not one single curator rather a committee that selected the artists and their artwork based on mailed applications. And there are even projects about the art on display - Russian artist duo Agency for Singular Research (Stas Shuripa, b. 1971 and Anna Titova, b. 1984) set up a platform for audience participation in front of some of the works on display for lectures, conversations, music and performances. With no curator freedom of expression is curtailed only by the budget, in this case it is limited as Atelier can only allocate modest sums of money to the artists. This experimental situation sharply delineates the range of problems regarding the presentation of the theme of censorship today and its understanding by the artists themselves.

What to show about censorship in a free country? Many of the artists at the Poush exhibition chose an aggressive poster style. Slogans, evidence of the bloody crimes of regimes, propaganda materials, and poster metaphors attracted attention, yet would have been perceived as weapons of struggle within totalitarian and authoritarian states. They would be a kind of guerrilla action, bypassing censorship. When there is no censorship, the power of such direct blows runs out. They become a rhetorical figure.

Central to any conversation about censorship is the demonstration of one's own identity that does not fit into the procrustean bed of socio-political and psychological templates and formats. This can be presented in different ways. What is most interesting in the context of censorship is a mode of dialogue in which the traumas and wounds of an oppressed identity become metaphors that are recognizable and expand the circle of sympathy to some universal formulae. For example, a handmade costume, a family history with dresses and fashions that speaks volumes about queer orientation and gender trauma. Similar artefacts, especially those made with needle and thread being a favourite today, were strong at Poush, such as a papier-mâché costume by Congolese artist Tickson Mbuyi (b. 1988). The elegance and glamour of paper fans, sequins and folds emphasize the ephemeral, impractical and illusory nature of their new body.

However, the main ideas of identity in the context of a conversation about censorship are more often reduced to the display of a wide range of various national exotics, which Europeans seem obliged to embrace with enthusiasm and wisdom. The meta position of a priori interest in the encounter with the Other is too easy a way of gaining sympathy and complicity. In a conversation about national identity, many links of communication are often missing. They are often left out precisely because of internal censorship, unwillingness to overload the recipient with complex information about another culture. Unfortunately, as a result, the multi-stage open dialogue turns into a display of postcolonial souvenirs for the entertainment of neoliberal society. This peculiarity also marks such big cultural events as the Venice Biennale. Its theme this year rhymes very much with Atelier des exiles: ‘Foreigners everywhere’, that is, ‘outcasts everywhere’.

Reflecting on problems of censorship, I am closer to the position that Theodor Adorno defined in his time. Dialectics is negative. And criticism can be deferred, not obvious, and not straightforward. Even talking about the music of Beethoven and the Baroque, it is today possible and necessary to feel acutely the wounds of modernity and to respond to them. Also in Paris, in the sprawling historical exhibition ‘Figures of the Fools. From the Middle Ages to the Romantics’ that opened parallel to ‘Censorship’ in the Louvre, the image of the fool was presented in a huge thematic register. And this spectrum helped to topple the theme into the most acute experience of modernity with the dictates of the dominant figures of the ruler among others. In one part, the fool appeared as a jester yelling out the truth at the thrones of all-powerful kings. And the foolishness proved to be an escape from censorship. But at what cost? In another part: the kings themselves were documented as maddened idiots, plunging their countries into seas of blood, degradation and poverty.

I like this kind of deferred criticism in the Poush exhibition in the case of Russian emigre Pavel Polshchikov's (b. 1998) work ‘A Simple Guide to Totalitarian Alchemy’. Alchemical emblems and diagrams of the great workings of nature, the perfection of human beings on the divine path are turned into pictograms appropriated by repressive services of control and violence. As the artist himself says, one can enter this puzzle of interesting mysteries in the format of video and baroque collages, but one cannot exit. This is also the situation with the position of the artist in a totalitarian/authoritarian state: it is impossible to talk about censorship because the subject matter is not allowed to be shown. We are only able to mark the territory of the discussion and the problem, which refers to the notion of ‘another place’, heterotopia, or perhaps ‘no place’ at all, atopia. The thematisation of unfree conversation within hyperlinks and cultural references provides an opportunity to gain an honest and complex philosophical perspective on the traumas of Being today.