Pawel Kowalewski. Golden Boy - Putin, 2017. Polyurethane resin covered with 24 сarat gold leaf. Photo by Ekaterina Wagner

Art inspired by headlines: a thought-provoking exhibition in Krakow

A multi-faceted show called ‘Politics in Art’ at MOCAK in Krakow explores the ways artists from different countries treat Europe’s most burning issues from Brexit to migration. And it shows how creative minds reach far beyond the simplistic narratives in the media.

Russian artist Pyotr Pavlensky (b. 1984) is the poster child for ‘Politics in Art’. The show opens with documentary photographs of street rallies in Krakow and Warsaw which address a slew of causes from anti-abortion laws to the migration crisis on the Belarussian border. You half expect to come across stories about artists as victims of a regime, flagbearers of resistance and representatives of a nation’s conscience. Yet the message behind ‘Politics in Art’ turns out to be much more nuanced. The soundtrack in the first hall of the show, surrounded by the documentary photos, is the 1978 iconic folk-rock protest song ‘Mury’ (Polish for The Walls). The lyrics and melody, oozing pathos, hide an ambigous meaning: what first seems to be a Perestroika-style hymn to freedom and liberation, turns out to be a pessimistic warning of a revolution that ends up devouring itself. According to Polish poet Jacek Kaczmarski, the “who is not with us is against us” attitude of protesters only leads to more injustice and oppression. The lonely singer is juxtaposed with a crowd in this sobering afterthought to Pink Floyd’s The Wall.

The exhibition is the work of three curators, Maria Anna Potocka, Agnieszka Sachar and Martyna Sobczyk. They pull it all together not just by grouping works on the same subject, such as the European Union or Nationalism, but also by trying to reveal things that are shared in common. The human body as a political subject is one of the persistent themes in the exhibition. Photographs of actions by Pyotr Pavlensky who harms himself without fear and considers his arrest an integral part of his performance, are hanging opposite to the ‘Skin Stone’ project of German artist Jakob Gansleimer (b. 1990). This is a series of photographic portraits of former neo-nazis who are trying to erase their tattoos with symbols of the ultra-right, regretting the fallacies of their youth. Displayed next to them are ready-mades called ‘Blood Brother Bibs’ by Ukrainian Daniil Galkin (b. 1985) who ordered children’s bibs with nationalist logos and slogans in online shops, showing how the same fallacies are passed on from one generation to the next.

Symbols and signs and their multiple meanings seem to fascinate both the artists and the exhibition’s curators. Simple directional signs become a way to divide and oppress in a project by Bosnian born, Germany based Sejla Kameric (b. 1975) called ‘EU and Others’. During the Manifesta 3 biennale in Ljublyana she had hung familiar airport signs ‘EU citizens’ and ‘Others’ over numerous bridges in the city. At the exhibition they are rather crudely likened to the ‘Europeans Only’ signs from the era of South African Apartheid, photographed by Polish artist Pawel Kowalewski (b. 1958). One of the most amusing works in the show is a video by Lithuanian artist Deimantas Narkevicius (b. 1964) called ‘Once in the 20th century’ (2004). The artist simply reversed the documentary footage of people dismantling a monument to Lenin in Vilnius in 1991. On a bright sunny day the massive statue is erected on its pedestal amidst cheers of the euphoric crowd. Who needs a better example of how rapidly historical tides may change, and how political symbols and their meanings, and the events taking place in front of our eyes can be reversed?

The violence of state oppression is a subject with little ambiguity yet artists still manage to surprise us with their non-linear narratives. Polish dissident Zbigniev Libera (b. 1959) imprisoned for distributing opposition lealflets, surreptitiously took pictures of his penal facility with the camera that his wife had managed to pass to him. In his series ‘Hrubeiszow’, the penal camp looks like a summer resort surrounded by barbed wire. Inmates sunbathe peacefully on the grass, as if to prove that real freedom comes from within.

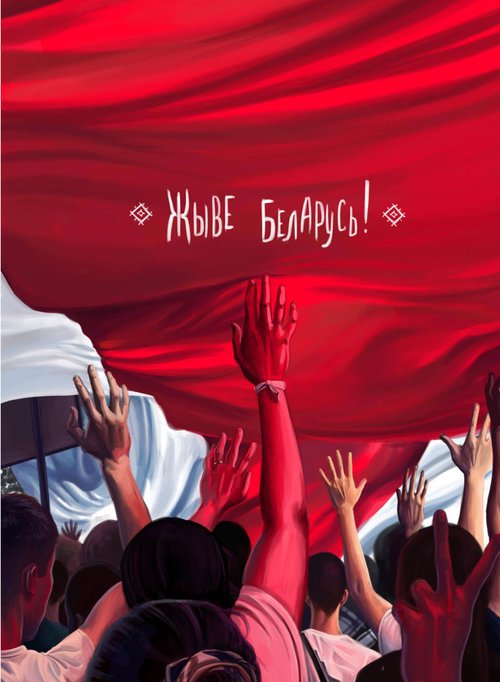

Russian artist and activist Artyom Loskutov (b.1986) has created an abstract artwork called ‘Belarus’ by beating the canvas aggressively with a police baton dipped in red paint. This allusion to multiple acts of violence and torture performed by the Belarusian police during the street protests of 2020-2021 requires no explanation. Yet, Belarusian artist Rufina Bazlova (b.1990) turns reflection on political repressions into group therapy. She creates designs for embroideries, depicting the stories of political prisoners by means of traditional folk patterns, and posts them online for people to use. The craft becomes a form of meditation and an act of empathy. Along with the design, you receive contact details of a prisoner so you can write them a letter if you wish. Anyone can download them and make these embroideries while pondering on the fates of the victims of the regime.

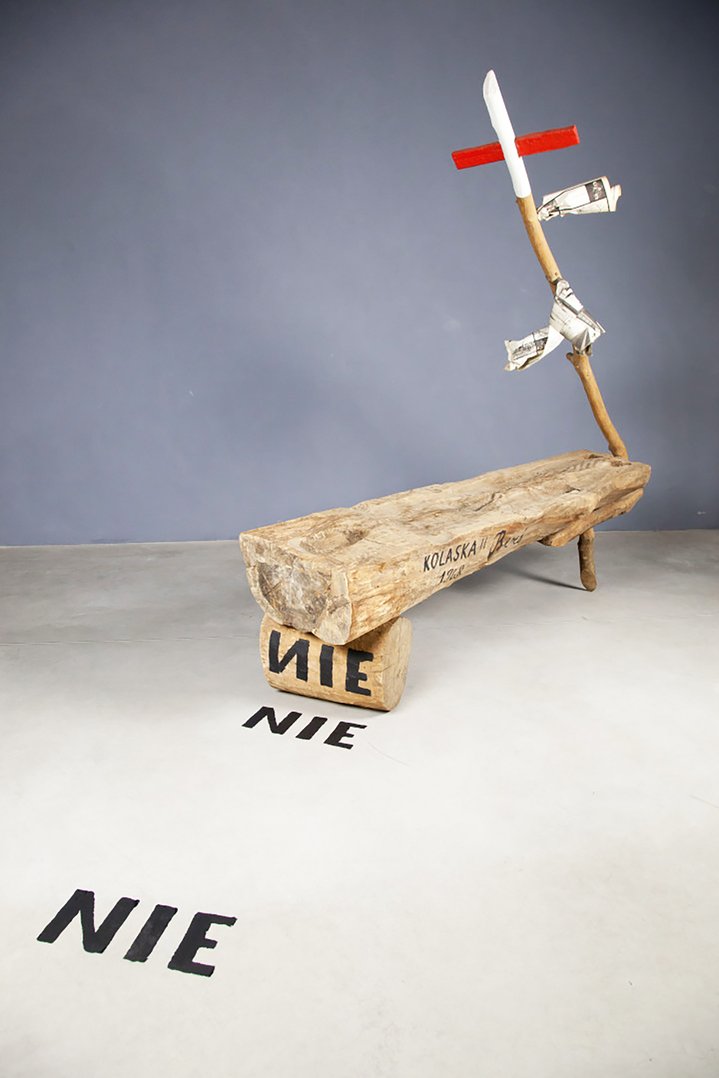

The intentions of an artist can be understood, and often misunderstood, in different ways. This was the fate of a sculpture by the Polish living classic Pawel Althamer (b. 1967). Is there something ambiguous in the birch trunk with a carved and painted face of the late Polish president Lech Kachinsky, who died when his plane crashed near the Russian town of Smolensk, hitting a birch grove? The artwork angered the public so much that it had to be taken off view. Sometimes a picture that goes beyond being black and white is too bright for the world to bear.