Art from Ukraine and about Ukraine on view in Venice

Otobong Nkanga. Lined with shivers sprouting from the rock, 2021. Unearthed – Sunlight, 2021. Courtesy of the Artist and Castello di Rivoli Museo d'Arte Contemporanea

The exhibition ‘From Ukraine: Dare to Dream’ by Pinchuk Art Centre in Venice shows the Ukrainian tragedy as part of the drama of dehumanisation.

Perhaps it is in Venice that the title ‘From Ukraine: Dare to Dream’ feels more organic than anywhere else in the world, in this beautiful city which, in the words of John Ruskin, was built by people who were ‘persecuted but not forsaken, cast down but not destroyed’ and who had no home left on earth but who ‘looked for one to come’.

For more than a decade, during the Venice Biennale, works by shortlisted artists in the Pinchuk Art Prize for artists under 35 have been shown by the Pinchuk Art Foundation, which was founded in 2006 by Victor Pinchuk, a metallurgical magnate, son-in-law of former Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma, collector and philanthropist. While the opening of Pinchuk’s exhibition was always considered one of the big social events of the opening week – past guests included Elton John, the Clinton family, European politicians and lobbyists – now only the charter yacht Odessa moored in front of the closed palazzo on the Zattere, until recently the headquarters of the V-A-C Foundation of Russian billionaire and philanthropist Leonid Mikhelson, is a reminder of a former life.

Leonid Mikhelson has closed his palazzo – there are traces of a Russian presence only in the restaurant Sudest 1401, still operating in the courtyard, where the walls are pasted with posters of exhibitions in Russian, including a film forum at the Yunost cinema, Ragnar Kjartansson’s performance ‘Sadness Will Overcome Happiness’ at the Mayakovsky Theatre, Kirill Glushchenko’s exhibition ‘The Beautiful Face of Our Daily Life’ and, of course, the names of international stars. Today, inscriptions in the Cyrillic alphabet are read only by rare visitors of the restaurant who come in for a plate of pasta and a glass of red wine.

“So, are we forgetting the Russian language?” – a tall, large man asks his companion with a nervous laugh as she crosses the threshold of the Palazzo Contarini Polignac, where the Pinchuk Art Foundation has chosen to hold its exhibition this time. There is nothing about prize winners now, the exhibition is a showcase of initiatives over the past year, as Pinchuk Art Centre focusses its efforts now on showing Ukrainian art on the world cultural scene.

The huge, crumbling Palazzo Contarini Polignac, one of the most important Venetian Renaissance palaces with richly painted wooden ceilings, soiled silks on the walls, empty bedside niches, is open to the cool spring wind: it plays in the courtyard with potted palm trees and lemons and flies away in waves out to the Grand Canal through the windows and the front entrance.

Like a road sign, a screen is stretched across the entrance, with images broadcast on both sides. This is Nikolay Karabinovych’s (b. 1988) video installation ‘Even Further’ from 2020, which is part of the collection of the Belgian museum M HKA. The artist explores the history of his family with its Greek and Jewish branches and collective individual memory. The tour bus arrives at the Kuyalnik estuary, people get out, listen to the guide, get on the bus and leave. The simple story is looped in a circle. Near the estuary are catacombs, where Odessa residents hid during the Nazi occupation in World War II. The melody sounding behind the scenes is considered a folk tune by both Greeks and Jews. Some sing it with joyful lyrics, while others sing it as a memorial. The artist's multi-page reflection on the history of the coexistence of different peoples on the same land, references European cinema and philosophy, including Deleuze, Robbe-Grillet, Fellini, Claude Levi-Strauss and Louis Buñuel. They all speak of the importance of repetition and remembrance, as if justifying the bus appearing on the screen again and again with urgent frequency. The ordinariness of the action, the meaninglessness of everyday life in a deliberately conventional, unattractive landscape, where many people felt hope, said their goodbyes to life, died and were saved, evokes the tired doom of an apocalypse. And this is only the prologue. The wind from the canal still moves the curtains separating the exhibition space of the palazzo from the everyday life of contemporary Venice.

The theme of rebirth and transformation resounds in Anna Zvyagintseva’s (b. 1986) installation ´Stick a Stick´ (2019–2022). The artist recalls walks in nature with her grandfather, artist Rostislav Zvyagintsev (1938–2018), who used to cut twigs and draw the subjects of his future works on the ground and in the snow. Or he lit a fire with the twigs or fenced – a cut tree branch turned into an instrument of fantasy and creativity. “Like a tree without leaves stands my soul in the fields,” – a line written on a sheet of paper that Anna found in the workshop of her grandfather. This note, made in pencil, black-and-white photos of a field with shriveled leaves, are the artist’s personal story, her point of lamentation for her native land, native people. But willow twigs, collected by Zvyagintseva in a large terracotta floor vase blossomed, opened buds, gave shoots and leaves after the opening of the exhibition. The force of nature, having intervened, has become the director of this story itself.

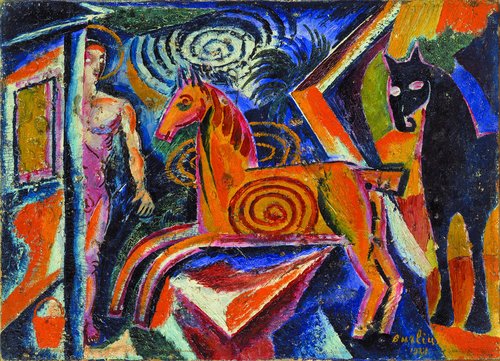

Nikolai Karabanovich’s next work from 2023, a video without sound lasting almost 19 minutes, is a story about the disappearance of blue and yellow colours in the landscape of a certain average city. The colours wash out slowly, almost imperceptibly, but with them goes the light: the city becomes like a lifeless ruin, a grey mass out of time and season. As a reminder of the process of dehumanisation, a comic painting space swings back and forth, depicting a figure ridiculously spreading its arms and legs in a dark maroon space – ‘Strange Games’ by Fyodor (Feodosiy) Tetianych (1942–2007), a Soviet and Ukrainian artist.

Having outlined in the prologue the theme of homelessness of people torn away from their roots but who have not lost their dignity, ancestral and family memories, the exhibition unfolds with total installations on the upper floors. Here there is a film about a Ukrainian actor, a young handsome man who returns from the front for a visit. Like Robbe-Grillet, the screenwriter endeavours to create action in the absence of action. How a man who has been to another dimension can return to everyday life. The actor does not shy away from the camera, but he can not act anything anymore. One of the most dramatic scenes is a long, awkward dialogue with his father. Nearby, in a large hall, there is a delicate wall painting with flying angels supporting each other with their wings, sexless naked people, sprouting branches and embracing lovers, where bunches of artificial baobab flowers are scattered on the floor - Allora and Calzadilla's project from 2024.

Mumbai-based artist Shilpa Gupta’s (b. 1976) installation is based on songs of resistance by different peoples in different periods of time. In a completely dark room, the viewer is invited to sit on a stool surrounded with speakers hanging above their heads in a circle, with male, female, and children’s heads singing songs ranging from guerrilleros’ “Bella ciao” to Ukrainian ditties. When your eyes get used to the darkness, you can see the music stands with the lyrics spread out – either in memory of disappeared performers or as an invitation to sing with them, or instead of them. Oleksiy Sai’s (b. 1975) maps from the ‘Bombed’ – a digital print drilled into the aluminum cover – are not only a documentation of the events taking place in Ukraine, but a summary of the wounds on the body of planet Earth.

A huge mountain of earth with sprouts bursting forth from the ground in rooms upholstered in silk, with windows overlooking the bay – Fatma Bucak’s (b. 1984) installation ‘Damascus Rose’ created in memory of the victims of the terrorist attack that took place in the Turkish city of Diyarbakir in 2016 – emotionally overlaps the works placed in the neighbouring rooms. Just images of a long, narrow horizon located on a mezzanine above the ashes and earth, which is illuminated around the perimeter, attracting attention as if signaling: as long as you are alive, you have your lifeline.