Architecture as Witness in Mikhail Rozanov’s Photography

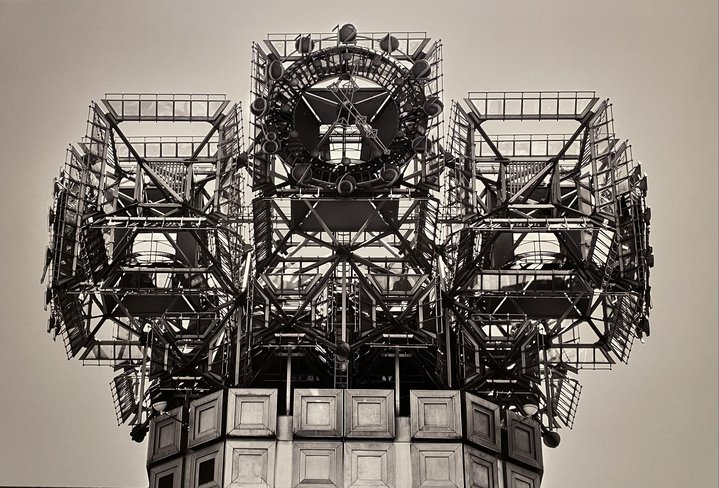

Mikhail Rozanov. Cube houses, 1974-1977. Architect Piet Blom. Rotterdam, 2020

Stark modernist architecture in black and white, presented in the exhibition ‘Steel. Concrete. Glass. Mikhail Rozanov’ at the Ruarts Foundation in Moscow, encourages us to reflect on the fate of Europe and the USSR during the Cold War.

The high tech and neo-modernist styles which you see reflected in these impressive, large-scale photographs are deafened by one of 20th century’s most hardcore architectural movements: brutalism. Here it is embodied in a wide variety of buildings from all over the world: there is the iconic UNESCO headquarters in Paris, the circus on Prospekt Vernadskogo in Moscow, the Picasso Tower in Madrid, the Berlin art gallery in the Kulturforum on a grand scale, then housing – here apartment buildings in Rotterdam — the 1962 Memorial to Victims of Deportation in Paris, libraries, university campuses and churches. All these buildings captured in large scale photographic prints on the walls of the historic halls of the neoclassical Talyzin estate (the A.V. Schusev Museum of Architecture in Moscow) are collectively more than just monuments of the era or milestones in the development of modernism; they give the impression of being witnesses in court, telling their case with dignity and pathos, bitterness and dramaticism.

"Brutalism is architectonic objects placed aggressively among the environment; it is a vigorous assertion of design; it is a revenge taken by volume and plasticity over the aesthetics of matchboxes and cardboard," wrote architectural critic Renato Pedio in 1958. This denunciatory quote, among others, accompanies the exhibition, underlining the stark nature of the brutal spectacle. The aesthetics of Rozanov's (b.1973) photographs allow us to see in this architecture the collision of European and Soviet history and not only the ‘revenge of construction’, but also the birth of imperial and neo-colonial ambitions. At the same time, there are still positive attitudes towards modernism even in the 1950s until the 1980s. In 1957, Joe Ponti, who had once supported Mussolini, called for a love of modern architecture, for its "will to clarity, order, simplicity, purity and humanity".

For Rozanov this exhibition is not a textbook of post-war modernist architecture. "The choice of subjects is personal. Architectural historians worked with me and made a list of buildings, the potential heroes. I did a lot of preparation, reading and collecting information about each building or monument as well as studied photos of them. Sometimes, when I finally found myself standing in front of a building, I realised that the shoot would just not work, maybe there was no space to step back and survey it from afar, or the area was too densely built up with ugly buildings. As a rule, out of the twelve monuments planned for each city, seven or eight were actually realised". Of the twelve cities the organisers had planned to cover in the project, they eventually stopped at nine because of the pandemic, but the geography of the project had already grown to huge proportions, including London, Paris, Milan, Belgrade, Moscow, Berlin, Helsinki, Rotterdam and Madrid.

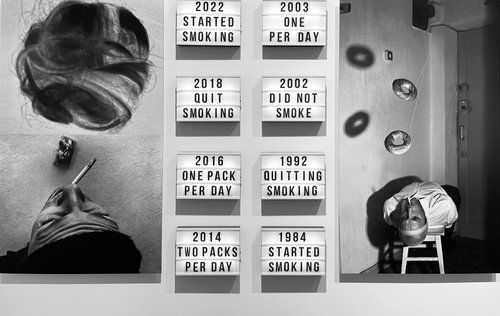

Today the genre of architectural photography, from the work of Bernd (1931–2007) and Hilla Becher (1934–2015), who recorded industrial buildings in Europe, to the French-Swiss master Hélène Binet (b.1969), who collaborated with Libeskind, Zumthor and Zaha Hadid, is popular with curators and collectors. Mikhail Rozanov's idiosyncratic style is monochrome, he uses a harsh light, lots of space without people, and all this gives rise to a kind of metaphysical flavour. Among his trademark techniques are exaggerated cropping and spectacular angles. Sometimes he leaves a large fragment of a building in the picture such as in the image of Rogers and Piano’s Centre Georges Pompidou, or a characteristic element, for example the metal composition on the building of the Presidium of the USSR Academy of Sciences (1967–1990), nicknamed ‘Golden Brains’. But as a general rule the camera takes in the whole building and the geometry of architecture is harmonized with the geometry of space, roads or skyline. "I used to shoot all sorts of things," Rozanov recalls, "still lifes, landscapes, portraits, fashion, but at some point, I realized that architecture fascinates me more than anything. My first real architectural shots were on the banks of the Moskva River and fragments of the main building of Moscow State University. This later became an exhibition called ‘Balustrades’, which I showed at Timur Novikov's New Academy in St. Petersburg. Since then, I only shoot architecture".

Mikhail Rozanov. Steel. Glass. Concrete.

Shchusev Museum of Architecture

Moscow, Russia

1 March – 14 May, 2023