An online exhibition by Russian Nobel Prize winner

Memorial, a Russian organization to support and promote victims of political repression was recently declared a foreign agent and closed by the Russian authorities. It is one of three Nobel Peace Prize winners this year, along with Belarusian human rights activist Ales Bialiatski and Ukraine’s Centre for Civil Liberties. Former members of the organization have launched an online project about history and memory.

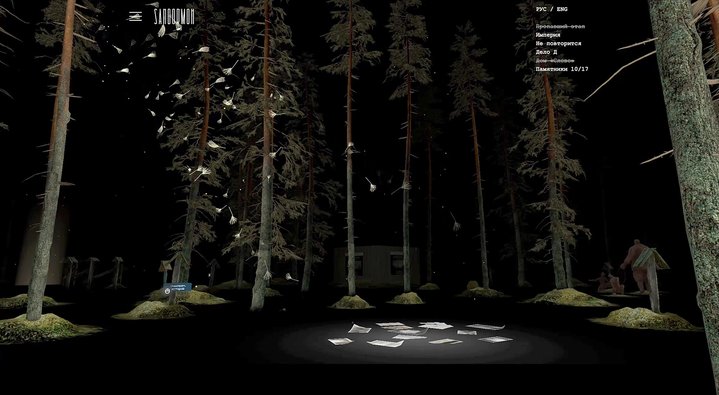

If the times and the social-political climate were different the Sandormoh exhibition would have taken place in one of Russia’s national museums or state exhibition halls, but in the Autumn of 2022, it exists only in an online platform. The exhibition resembles a computer game, but that is as far as the fun goes. It tells the story of one of the most tragic chapters in the history of the 20th century: the mass political repressions in the Soviet Union, which took place on a monstrous scale in the 1930s. Created in two languages, both Russian and English, the project brings together objects made by contemporary artists with a detailed account of the history of Sandormoh which is not just a cemetery, but an important symbol of historical memory and resistance against totalitarianism.

Part of the project is based on Memorial’s own documents. Since 1987 this public human rights movement has preserved and perpetuated the memory of political repression in the USSR, now declared a ‘foreign agent’ (a vehicle for foreign influence) in Russia. Although a Russian court took the decision to dissolve the organization on 28th of February this year, Memorial was still awarded the Nobel Peace Prize on the 7th of October. In the current atmosphere, it is not surprising that the curators of the Sandormoh project and some of the artists prefer to remain anonymous.

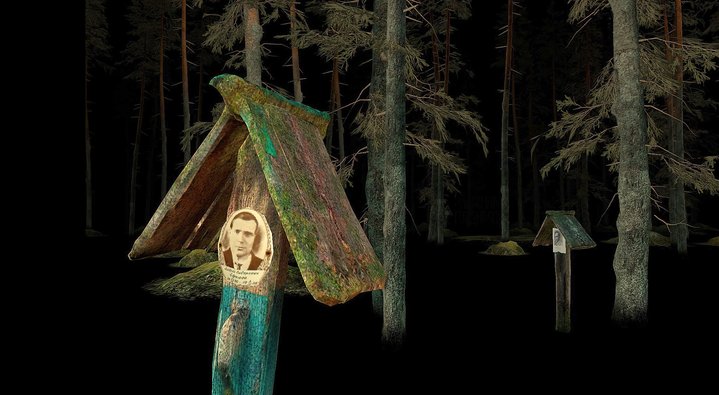

In the Karelian Forest, at Sandormoh (also spelled as Sandarmokh or Sandormokh), at least 6241 people were shot during 1937-38 alone. In 1997, historians Veniamin Iofe, Irina Flige and Yuri Dmitriev established the exact location where the bodies of prisoners from two Gulags were dumped in pits and buried. Since then, this mass grave has been given the status of a memorial. New monuments have been erected in the forest, there are plaques on trees with the names and photos of those executed; for local northern traditions there are ‘golubtsy’ memorial poles, and there are monuments which have been put up for the many different national diasporas in memory of their fallen compatriots.

For a tragedy on the magnitude of Sandormoh, not only what you say but how you tell the story is crucial, using intonation to help you create an atmosphere of verisimilitude. Museums have long been used to working with multimedia, presenting the most complex of material in a way that people formerly did not take seriously. In 2004 a virtual Gulag Museum was made by Memorial. According to the creators of this project, ‘Visitors to the exhibition find themselves in the Sandormoh forest, filmed by 3D scanning. The forest becomes not just the venue of an exhibition, but an alternative memory space’. Whereas in an exhibition the emphasis is normally on the formal characteristics of the works on show and their artistic merits, in the virtual world on the computer screen design becomes far more important. The journey through the virtual forest is accompanied by sounds recorded in the real Sandormoh and collaged by sound artist Pug Heel & Vip Zip.

Yuri Dmitriev has repeatedly spoken in interviews of how he guessed the location of the firing pits after seeing squares of soil subsiding in the Sandormoh forest. This is exactly what the virtual Sandormoh looks like: a dark, haunting forest, in which it is easy to get lost, as noted in the project’s opening credits. You can spend a lot of time here in this virtual space. An endless ribbon of minutes from a recent political trial, the 2016 case against Yuri Dmitriev, unfurls from one of the firing pits. This 66-year-old activist and local historian, who is now serving a lengthy 15-year sentence on trumped up charges of violent sexual acts towards a minor, far-fetched and repeatedly rebutted, is the subject of a special section called ‘Case D’. Another section ‘Lost Transit’ leads from the forest straight to the pier of the Solovetsky labour camp. The first group of 1,111 prisoners was sent from there by sea in the autumn of 1937. Dmitriev and his colleagues were not able to document the last journey of these men, which ended in Sandormoh, until six decades later. Now name after name appears on the screen and dissolves into the night. In another section called ‘Empire’, you enter the clock of the Spasskaya Tower of the Kremlin and find yourself surrounded by political slogans and posters from the last hundred years, from the Soviet times till today.

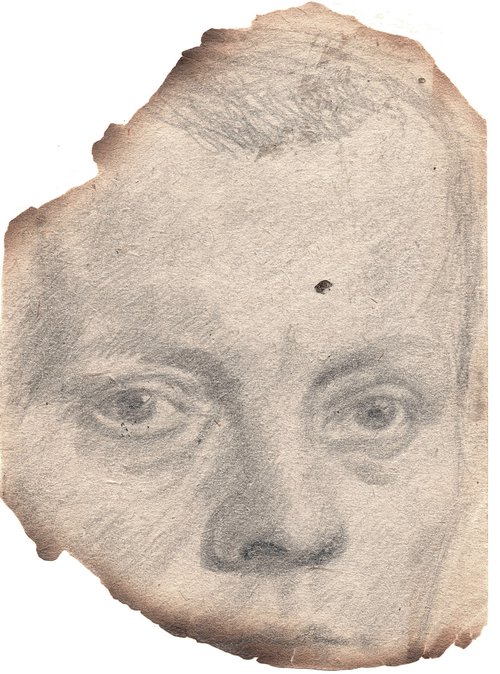

Among the seventeen artists whose works make up the ‘Monuments’ section, there are well known names, such as Andrey Kuzkin (b. 1979), who included in the virtual space a head from his ‘Heroes’ series (sculptures made out of bread and the artist’s own blood), or Alexander Shishkin-Hokusai (b. 1969), in whose ‘Breath’ soil rises rhythmically and hauntingly, as if over a quickly filled mass grave. Street artist Slava PTRK (b. 1990) set up a light installation in the forest with flashing words “We (don’t) remember, we are (not) proud”. Historian and new media theorist Lev Manovich set up the ‘Impossible Monument’ in the Sandormoh Forest, with sketches of monuments in the style of architectural studios of Frank Gehry, Shigeru Ban and Zaha Hadid. This project looks like a construction site behind a metal fence with the words ‘Start of the Construction. Never. Completion. Never’. However, one day leading architectural firms will compete for the honour of designing a monument here. October the 27th, marks the anniversary of the first day of the execution of the ‘lost’ transit from Solovki in 1937, and Sandormoh will once again become a place of commemoration for victims of the Stalinist terror. There are fragments of the speeches made at the Sandormoh commemoration rallies over a period of more than twenty years, such as ‘It won't happen again’, a phrase which has sounded like a mantra all these years and is increasingly difficult to say with the same conviction today.

Sandormoh project