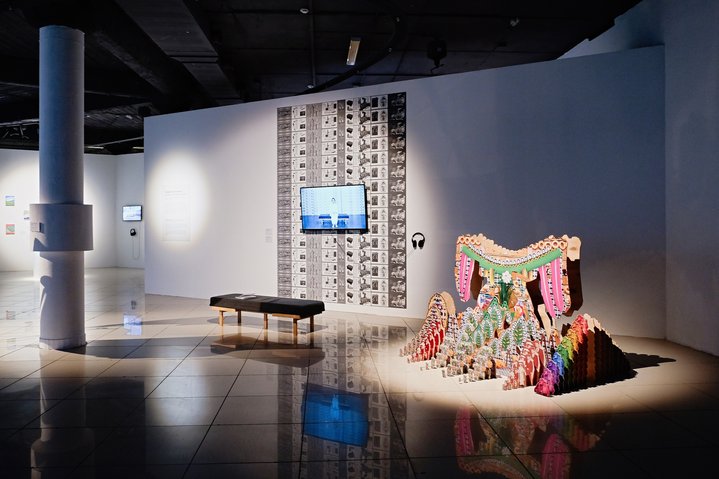

Alisa Gorshenina. Ural Snake, 2021-2023. Wild Happiness. On Both Sides of the Ural Mountains. Exhibition view. Perm, 2023. Courtesy of PERMM Museum of Contemporary Art. Photo by Ivan Kozlov

An Exhibition in Perm Shows Artists from the Urals in Search of Local Identity

This Summer the PERMM Museum of Contemporary Art is hosting an exhibition ‘Wild Happiness. On Both Sides of the Ural Mountains’. It is the first half of an ambitious two-part project exploring Urals art.

Perm is celebrating its 300th anniversary on a grand scale. The park zone on the Kama embankment is still beingimproved, the promenade itself having been launched just a year ago. A new building for the art gallery has finally been completed after four attempts (all big international competitions to design the building disappeared into oblivion), there is a zoo and a new hospital currently under construction, as well as many more new public spaces. Many streets are under construction, but when it starts to rain the water level rises to almost a metre – for those wanting to catch the a reinvigorated Perm this summer in the glory of its jubilee should put on their trainers and carry a pair of galoshes.

The PERMM Museum of Contemporary Art, which emerged in 2008, at the time of the so-called Perm Cultural Revolution initiated by gallery owner Marat Guelman (recently declared a Foreign Agent by Russian authorities) with the support of Oleg Chirkunov, then Governor of the Perm Region, is doing its bit for the anniversary celebrations with the exhibition ‘Wild Happiness. On Both Sides of the Ural Mountains’. The producers of the show were PERMM's director Nailya Allakhverdieva and independent curator Ilya Shipilovskikh.

Tucked away from the ‘Emperor’s Line’, the name given in Perm to the historic buildings built along the Kama embankment, deep in the Motovilikha industrial district, according to director Nailya Allakhverdieva, the PERMM Museum has undergone a transformation from a ‘flying saucer’, once alien, exotic, scarily unfamiliar to the locals, to a ‘neighbourhood museum’, a space where people voice real existential questions and look for answers.

The anniversary exhibition at PERMM is a part of an exchange project with Ekaterinburg’s Yeltsin Centre. The two industrial giant cities in the Urals, old rivals, are both celebrating the 300th anniversary of their founding this year. Joining forces, PERMM and the Yeltsin Centre are swapping exhibitions. The first is ‘Wild Happiness. On Both Sides of the Ural Mountains’ sent over to Perm from Ekaterinburg. A reciprocal exhibition curated in Perm will travel to Ekaterinburg thisautumn.

Curator Ilya Shipilovskikh, at the helm of the Yeltsin Centre's Art Gallery for six years who left his post in December 2022, conceived of the exhibition as a kind of summary of his tenure there. Each participating artist has his or her own corner presenting a snapshot of his or her exhibition at the Yeltsin Centre in recent years. The exhibition is laid out over three floors. The Yeltsin Centre must be applauded for its support of the development of contemporary art in Ekaterinburg. The exhibition is full of contemporary art stars, some very young, and there are others who are more established, including Krasil Makar (b. 1989), Alisa Gorshenina (b. 1994), Ekaterina Poedinshchikova (b. 1985), Liza Nesterova (b. 1991), Fyodor Telkov (b. 1986), Anna (b. 1989) and Vitaly (b. 1990) Cherepanov and Vladimir Seleznyov (b. 1973).

Taking inspiration from the novel ‘Wild Happiness’ by 19th century Ural writer Dmitry Mamin-Sibiryak, where the disintegration of a family goes hand in hand with the temptation of gold and the development of a gold mine, Shipilovskikh proposes we reflect on Urals identity, on how a society of factory workers, peasants, Old Believer merchants who fled from oppression to the Urals, Cossacks who conquered new lands, and indigenous peoples of the Urals has developed and transformed over three centuries. The floors of the museum are arranged as three differentplatforms for discussions, where questions are asked about the fate of nature, the land, clans, families, and of human individuality, corporeality and personal happiness.

While the so-called ‘mountain-factory civilisation’ (a term first coined in the early 1920s to define Urals identity, andreclaimed for the 300th anniversary) is exceptionally young from a historical point of view, the Mass Permian Extinction, when the Permian period of the Palaeozoic Era ended with the death of 96 percent of marine species and 73 percent of vertebrate species, occurred more than 250 million years ago. Artist Natalia Podunova (b. 1977) reconstructs the story. In her mockumentary photographs, dragonflies the size of helicopters are flying around, tree ferns are growing among the pipes in the industrial landscape, and giant insects are crawling through crowds of people. Proof of authenticity was provided by the Perm Museum of Local History: here is a fossil bone fish, there are fossil mollusks called goniotites. A virtual ancient globe of the Earth shows what our planet looked like in different eras. And the sound-art ‘Ural Ocean’ by Tatiana Zobnina (b. 1979) combines the sounds of motorways, of modern landscapes with the historical sound memory, the noise of the ocean. Photographs of contemporary reality show the consequences of the Permian extinction: in one of the images, for example, sad contemporaries marvel at toy dinosaurs spread out on the ground.

The work of Anna and Vitaly Cherepanov presents the landscape of the Urals as a game set with a green inflatable mountain guarding a lot of trophies in its secret compartments. Yet these are not gold-bearing veins and malachite deposits, but toys and trinkets created from recycled waste products of mass production of a sprawling, consumerist population. Addressing the people who inhabited this land which is rich in history and treasure, the artists explore certain social groups and the personal and family experiences of the conquerors of the Urals and Siberia. For example, photographer Fyodor Telkov for his project ‘Right of Faith’ photographs and interviews Old Believers. Sixteen artificially aged photographs are complemented by ten interview brochures on display opposite. The strongest document is an Old Believer kaftan spread out on the ground with its sleeves laid out in different directions. It seems that the stubborn interlocutor has flown off to heaven before realising the frailty of human life. Sergey Poteryaev (b. 1988) also tells us about the fragility of material things and the impossibility of overcoming nature in his series ‘Staraya Utka’, where the inhabitants of a village alongside an 18th century ironworks share the fate of the factory – they flourish and stagnatetogether with it. Mixing contemporary images up with archival materials of the residents of Staraya Utka, Poteryaev paints a three-dimensional picture of time, where past and present exist simultaneously and different generations of people meet one another.

Ekaterina Poedinishchikova captures not people, but moods in her ‘Chtonics’. Her ‘Swamp Spirits’ are multi-armed nude sirens. Their black and white bodies are illuminated by a golden background as if an Old Master painting. And the only references to reality are documentary photographs of forest thickets with fallen tree trunks, rough branches and peeling bark where either branches or scrawny hands are waiting to drag someone to the bottom of the swamp. There is also the ‘Spirit’ itself, drawn in white acrylic on black paper, as meaningful as a stone sculpture of a young pharaoh. This is perhaps the most accurate visualisation of Mamin-Sibiryak's novel, which, according to the curator's plan, should serve as the connecting thread of this story: "Man's intrusion into the life of nature in order to reproduce its beauty, in one way or another, is every time broken in the most merciless way, like the hallucinations of a madman," so wrote the author of ‘Wild Happiness’.

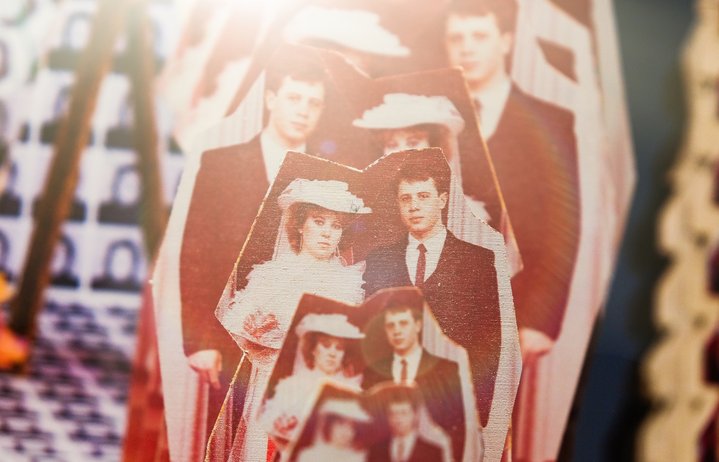

However, you don't need to perform shamanistic rituals to summon the shadows of forgotten ancestors, it's enough to open a family album and talk to your mother, as demonstrated in Vladimir and Nadezhda (b. 1948) Seleznyov's project ‘Rags’. The project emerged during the pandemic quarantine, when artist Vladimir Seleznyov sitting in Ekaterinburg called his mother Nadezhda in Nizhny Tagil. They were remembering relatives, so Nadezhda cut and sewed some textile compositions together from old garments and fabrics, and Vladimir printed portraits of the heroes of his family chronicle on fabric, thus combining both his andhis mother's work. This is how the exhibition-family chronicle came into being: grandfather Fyodor, thanks to whom Vladimir became an artist, sits on rags against the background of a white palisade, and behind the tulle curtain the shadow of his grandmother flutters – everything that his grandson's memory has preserved about her.

The third floor, like the top layer of a pyramid, explores the theme of personal freedoms. And here there is no equal to Viktor Davydov's (b. 1953) project ‘Gallery of Art Videos’, which was aired on Ekaterinburg television from 1996 to 1998, where everyday scenes are played out with absurdist grotesque and irony. "We thank the people of the Urals for who they are," the scriptwriters invariably concluded at the end of each episode.