A thought-provoking exhibition of Ukrainian-Russian sculptor Alexander Archipenko has opened in London

Archipenko’s works caused a stir in Venice in 1920, when the Kyiv-born artist represented Soviet Russia at the Biennale. Now his works are on view at London’s Estorick collection, along with those of his Italian contemporaries, including Modigliani.

Archipenko’s works at the 1920 Biennale allegedly caused such controversy that the local Catholic authorities threatened to excommunicate anyone who went to see them. His drawings, sculptures and what he called “sculpto-paintings” on show received a mixed critical response, ranging from praise to incomprehension to outright mockery. Some critics interpreted his works as Bolshevist art, while others read them in relation to the contemporary Italian school of “metaphysical painting”. Such Proteanism characterised Archipenko’s reception throughout his career. In 1960, a few years before he died, the artist reflected: “I find my name used by groups to which I never belonged, for instance the Dadaists and Futurists. In reality, I am alone and independent”.

Archipenko was born in 1887 in Kyiv (then in the Russian Empire, now Ukraine). After studying art in Kyiv and Moscow, he moved to Paris at the age of 21. He found the École des Beaux-Arts stiflingly academic and dropped out after two weeks to set up his own studio. He lived in La Ruche in Montparnasse, an artists’ colony that included other émigrés such as Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920), Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) and Marc Chagall (1887-1985). His sculptures from that time, mostly depicting female figures in sorrowful poses, show the artist’s already distinctive style, though they were made from a wide range of materials including bronze, stone and wood.

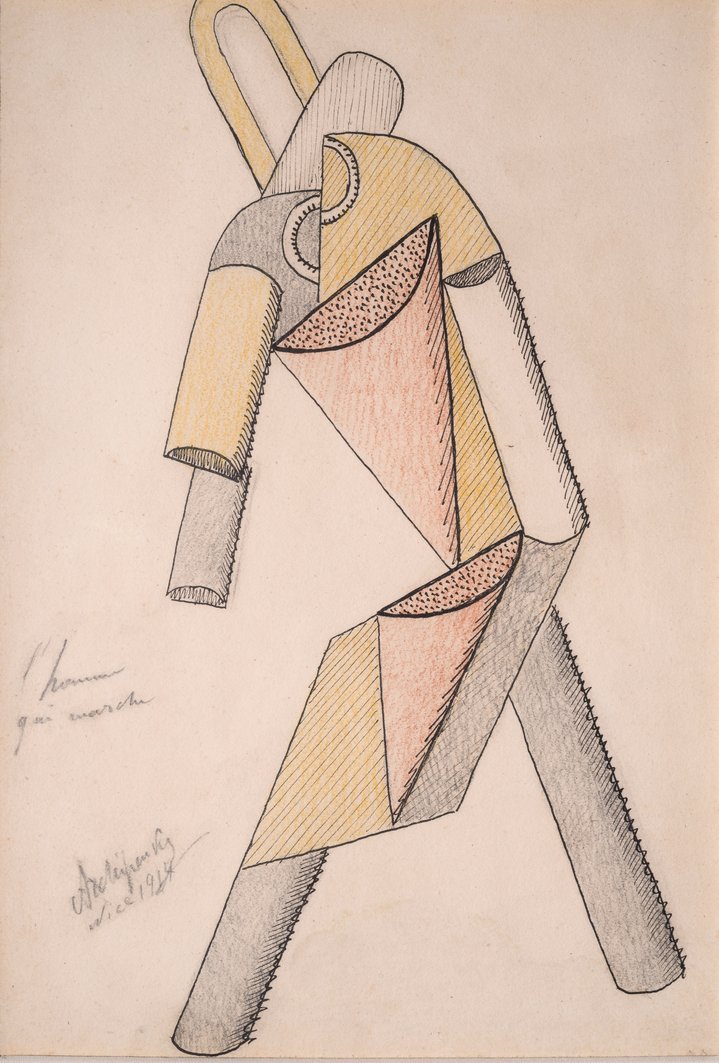

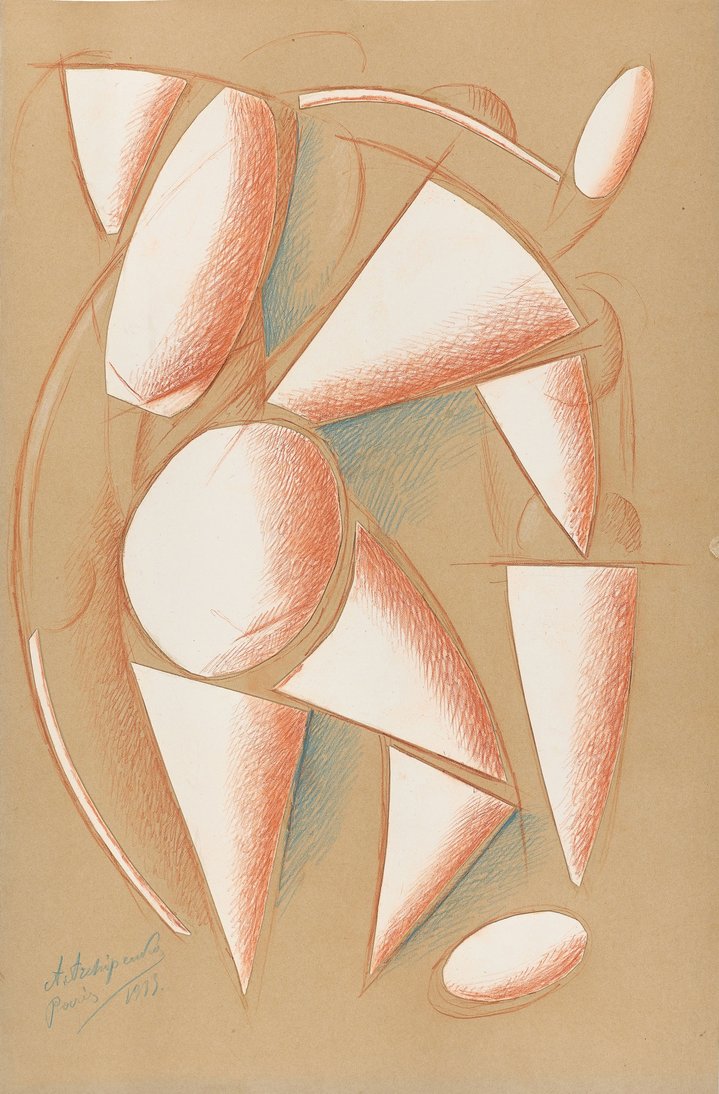

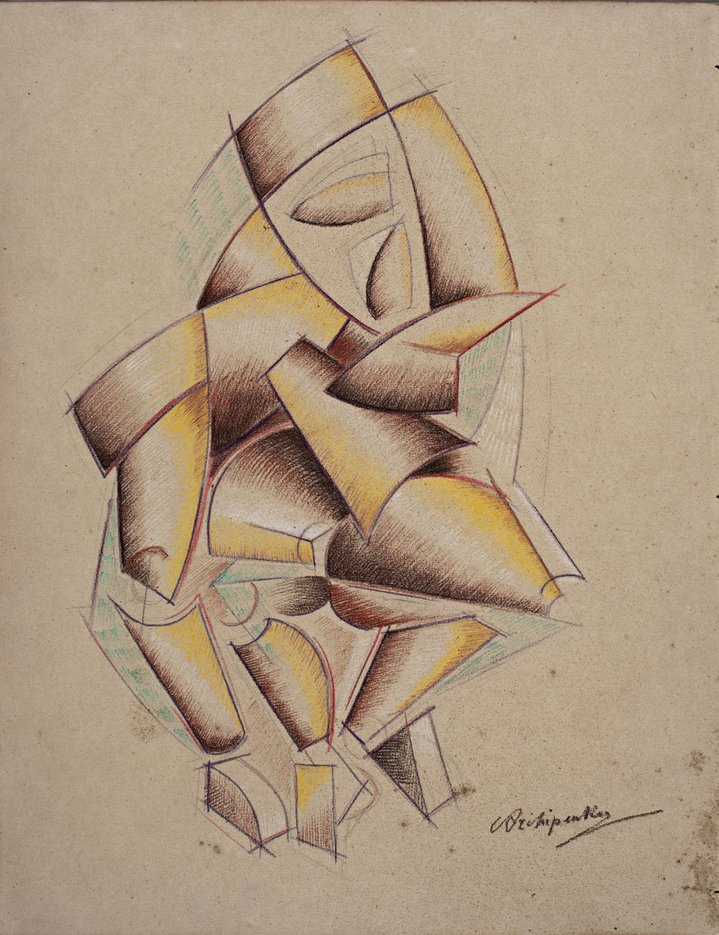

In the years that followed, Archipenko experimented increasingly with colour and movement. Sculptures like Boxers (1913-14) captured the dynamism of moving figures through smooth, abstracted forms. Others went further. His Médrano series of circus performers, made of multicoloured wood, tin and glass, had movable protruding parts. Even seemingly static figures, such as those in two sculptures titled The Kiss (1910, 1911), look like they are in motion, as they arch and curve. His Kisses may well have been made in response – or rather, riposte – to the famous sculpture of the same name by Auguste Rodin, whose works he dismissed as passé and unrefined. Rejecting his direct artistic predecessor, Archipenko harked back to the art of a more distant past: Cycladic, Hellenic, Ancient Egyptian. He used these ancient sources and influences to create art that was strikingly modern.

Around this time Archipenko also pioneered his signature medium of “sculpto-painting,” in which he painted directly onto sculptures to create spatial illusions. After a productive couple of years between 1920-23 (during which he was included in 25 exhibitions and the subject of four monographs), he emigrated to America with his first wife, the German sculptor Angelica Forster. That same year, he opened an art school in New York as he had done in Paris. He worked as an art teacher and lecturer for the rest of his life, while also continuing to make sculptures and “sculpto-paintings”, sometimes with industrial materials such as Formica and Bakelite. However, he never again achieved the success and prominence of his Paris years.

A new exhibition at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art in London running until 4th September 2022 features works from various points in Archipenko’s career and explores his two-way exchanges with members of the Italian avant-garde. Small and elegantly curated, the exhibition creates some beautiful pairings: Archipenko’s sculpture Madonna on the Rocks (1911-12) and Modigliani’s work on paper, Nude with Cup (c. 1916). Or, in the other direction of influence: Mino Rosso’s abstracted bronze sculpture, Motorcyclist(1931) and Archipenko’s later bronze relief, Abstraction (1959). This exhibition proves that, despite his protests about his own independence, Archipenko was intimately connected within international networks and communities of artists. Together these artists grappled with the challenge of creating something new and meaningful, often against the backdrop of extraordinary social and political turmoil.