A scandalous Moscow Biennale

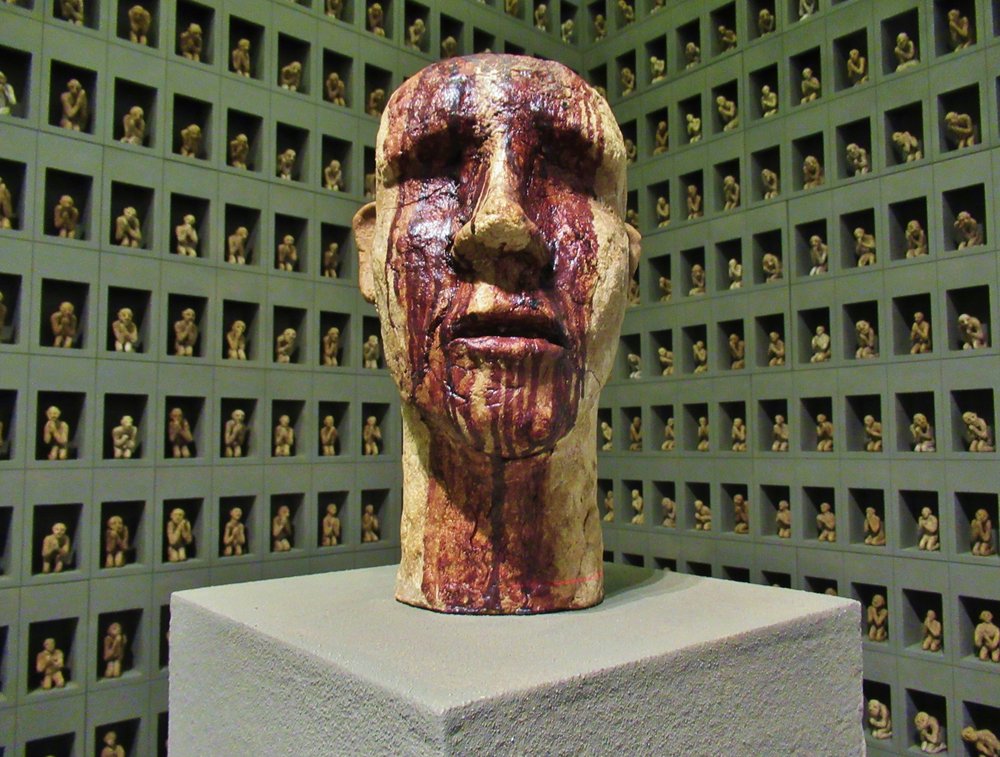

Andrei Kuzkin. Prayers and Heroes, 2016–2019. Installation. Photo by Simon Hewitt.

Where Russian artists far outshone foreign guest performances.

The 8th Moscow Biennale opened at an annex of the State Tretyakov Gallery on October 31, less than a month after the event’s supremo, Julia Muzykantskaya, had to refute claims, made by artist who participated in the 2017 biennale, that many of them had not been paid and that the organisation of that show had been disastrous.

On the eve of the Biennale, Muzykantskaya received the heavyweight backing of Vasily Tsereteli, the head of the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, who hosted a lavish Georgian dinner for staff and participating artists. “Julia took on the Biennale when no one wanted it,” he declared. “Many people criticize her. I admire her courage.”

Muzykantskaya had nothing to add to her October 4 statement when interviewed at the Biennale press preview on October 30, but the event’s organization again left much to be desired.

“There is no organization at all,” growled the artist and architect Alexander Brodsky (b. 1955), who was detained for 15 minutes at a side-entrance before being allowed to add the final touches to the white-tiled tunnel he had created to showcase a nostalgic video shot in a Kitai Gorod underpass back in 1992, featuring half-blind musicians strumming the folk-song “Эх Дороги” (“Oh, roads”).

Brodsky had wanted to litter the floor beneath his video with wastepaper and cigarette butts, but the building’s head of security told him he couldn’t, not because of any fire hazard, scoffed Brodsky, but because the bureaucrat thought the litter looked ugly. Brodsky eventually replaced his cigarette-ends with crushed beer cans.

That artist strikes a truculently untidy note in a show that otherwise looks like a spacious VIP Lounge, with Minimalist vistas of blank wallspace, concocted by the Berlin-based jet set architect Sergei Choban, in harness with the Biennale’s unlikely Curator, the swivel-chair-loving opera director Dmitri Chernyakov. The vast upper hall of what used to be the Central House of Artists, and is still known as such by most Muscovites, has been peppered with individual booths and stunningly transformed beyond recognition, with new lighting and air-conditioning installed.

The works on show are large in scale, but small in number (just over 50). Two-thirds of the 33 artists are from Russia (12), while Austria and Germany contributed 10 in total. The latter contingent was provided by Vienna’s Albertina, known for Old Master Drawings until ailing DIY salesman Karlheinz Essl foisted his raucous post-war art collection on the institution in 2017.

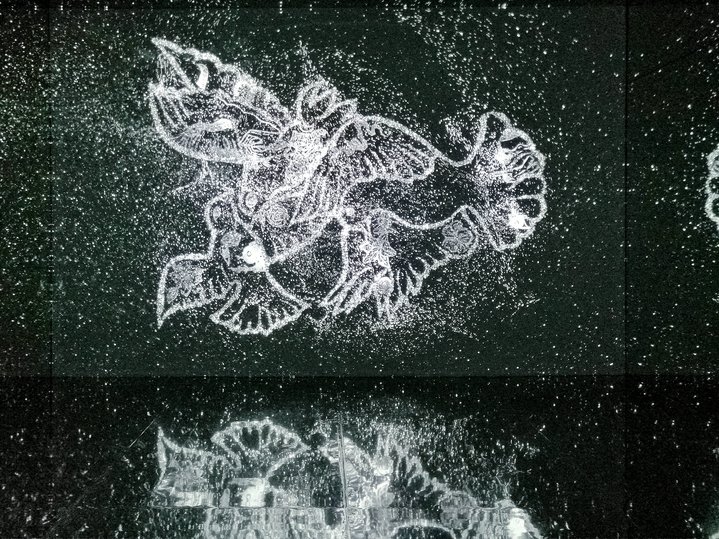

If the Moscow Biennale (meaninglessly entitled Orienteering & Positioning) had concentrated on a Russian/Germanic dialogue, it would have greater coherence, but a sprinkling of artists from the USA, China and the Middle East add disconcerting glamour, kitsch and digital eye-candy – the latter provided by Leyla from Baku (who just happens to be the daughter of Azeri strongman Ilham Aliyev and a member of the Biennale’s Board of Trustees).

Russian artists hold their own against the Albertina offerings. Andrey Kuzkin (b. 1979), with his bread-and-blood heads and tiny figurines arrayed in hive-like cells, out-stares Georg Baselitz. Maria Kulagina’s (b. 1961) towering Fisherman column puts Muntean/Rosenblum’s dodgy figurative works in the shade. The frenzied surfaces of Vitaly Pushnitsky’s (b. 1967) paintings, criss-crossed with strips of torn white canvas, stirringly engage with the ultra-smooth Alex Katz.

Natalia Sitnikova (b. 1978), her painting artfully displayed lying at ground level, spars abstractly with a Hermann Nitsch triptych; Egor Plotnikov (b. 1980), with an Ubermenschpaper sculpture, and Alexei Luka (b. 1983), with a wonky hut, have more to say than Xenia Hausner’s paintings and Tony Matelli’s shattered piano alongside.

Evgenia Buravlova (b. 1980) and Pavel Otdelnov (b. 1979) both exist splendidly in isolation withpaintings-and-video projects with Buravlova wistfully evoking family and nature and Otdnelov with an elegant attack on Russia’s burgeoning landfill industry.

Maria Suvorova (b.1973), however, is done no favours by having three of her unnecessarily large architectural paintings placed beside a view of Rome’s Castel Sant’Angelo by the infinitely more talented Valery Koshlyakov (b. 1962).

As the Biennale’s Russian works are mostly from 2018/19, many of them specially commissioned, the presence of a 1994 Koshlyakov is hard to fathom. Perhaps its ownership by the collectors, Ekaterina and Vladimir Seminikhin, has something to do with it.

A lack of publicity and PR is complemented by a monumentally uninformative Biennale website, bereft of images of works in the show (ditto the Biennale Facebook page). But there is time to remedy the situation before the Biennale closes on January 22.

8th Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art

Moscow, Russia

31 October 2019 – 22 January 2020