A new post-war era: Not Forever

Curators of the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow have made an ambitious attempt to re-write the history of Soviet (and Anti-Soviet) art of the 1970s and 1980s. However, the huge ‘NotForever’ exhibition has received a mixed response from the local art scene.

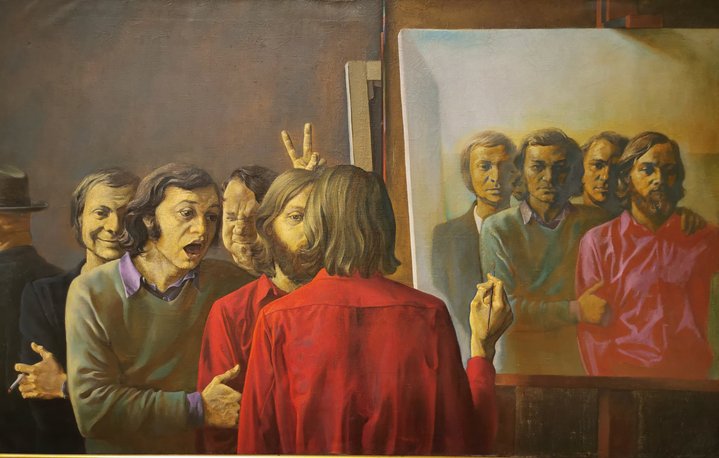

“Usually we do not exhibit this painting, because it frightens the museum’s employees,” says Kirill Svetlyakov, curator of the exhibition projects at the State Tretyakov Gallery. The curator was leading a tour through ‘NotForever’, a sweeping exploration of Soviet visual culture between 1968 and 1985, on view through October 11.

Svetlyakov had paused before a 1984 painting called ‘Carnival’ by Nikolai Yeryshev (1936–2004), a prize-winning participant in Soviet official exhibitions. Today, however, he is best remembered as a student of the Socialist Realist maestro Aleksandr Deineka (1899–1969).

In ‘Carnival’, viewers might sense a hint of Deineka-esque otherworldliness in the motley crowd of revelers, who line the palaces along Venice’s canals. Among the demonic-looking creatures, appears a joyful Mickey Mouse. Things get stranger. Instead of fireworks, Yeryshev used missiles to give his sky a fiery glow. “Most of our guides are unsure how to explain this work,” Svetlyakov comments.

One way of gauging the impact of the ‘NotForever’ exhibition is whether it delivers a language for understanding bizarre works like ‘Carnival’.

‘NotForever’ is the second part of a trilogy that the Tretyakov is staging about postwar Soviet art. It follows the 2017 show ‘The Thaw’ and will be followed up by the art of ‘Perestroika’. ‘NotForever’ covers the years during which the late Leonid Brezhnev ruled the Soviet Union, a period that has gone down in Russian history as ‘Stagnation’. That word remains conspicuously absent in the Tretyakov’s vocabulary. Its curators Yuliya Vorotyntseva, Anastasiya Kurlyandtseva, and Svetlyakov explain that their aim was to focus instead on the complex cultural psychology of late Soviet Socialism.

Some 450 works from the Tretyakov’s collection, as well as regional and European institutions are on show. Highlights include moments of beauty and strangeness, such as Mikhail Schwarzman’s (1926-1997) mystically totemic face in ‘Redemption’ (1972), or the real or imagined travels in Vitaly Komar’s and Aleksandr Melamid’s ‘First Duty-Free Trade Between the USA and the USSR. We Buy and Sell Souls Project’ (1979).

Flashes of wit and poetry appear in the Gnezdo Group’s ‘Chart of History’ (1976) which is structured around Party congresses, as well as the politically orchestrated ‘Blow-Up’ (1978) by Valery Shchekoldin (b. 1946), a clever photographic series of large-scale murals and banners of Brezhnev under construction, which shatters the leader’s monumental wholeness.

Overall, the curators treat the exhibited works as if stuck in amber, as mirrors of a particular historical moment. The installation reinforces this point, as it uses period colours and wallpaper patterns throughout. This tends to treat the works as specimens of another era, instead of articulating their meaning to the contemporary world. The firestorm of debate among local critics and artists about the exhibition indicates that while the Tretyakov has createted new post-war canons, its audiences will continue to debate if and how these works can speak to what matters today.