A New Book on Bar-Gera, Israeli Collectors of Soviet Non-conformists

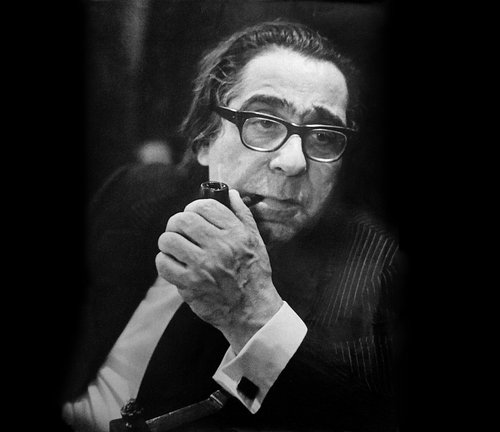

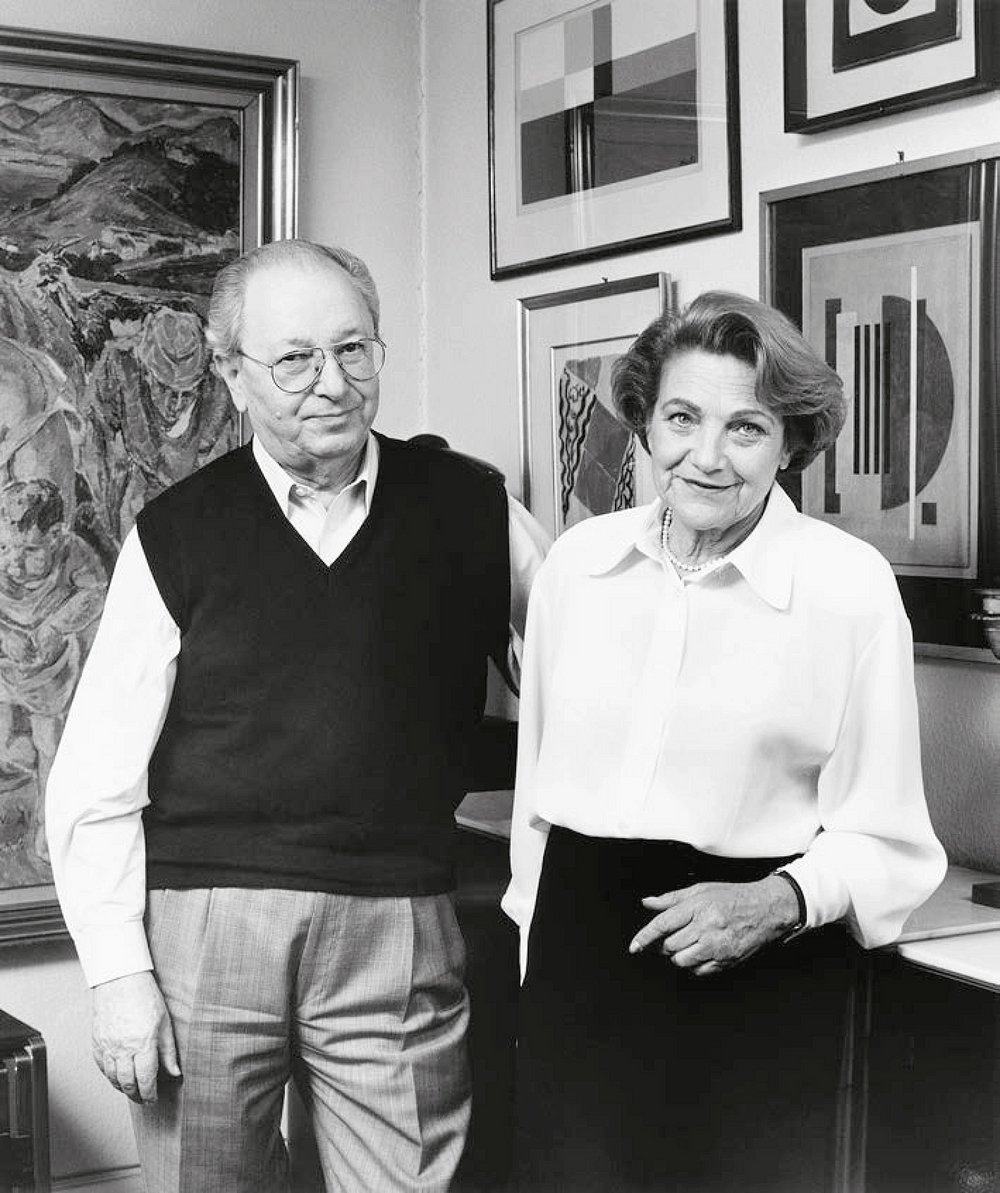

Kenda and Jacob Bar-Gera in their flat in Cologne, surrounded by artworks. Kenda and Jacob Bar-Gera and their Unique Collection. Jerusalem, 2022. Courtesy of Jerusalem: 'Discovery Routes' – The Association for Jewish History and Culture

‘Kenda and Jacob Bar-Gera and their Unique Collection’ by Alek D. Epstein and Sofia Birina promises to tell the “untold story of passion for art and dedication to building bridges”. However, curator and art critic Alistair Hicks thinks that it does not quite live up to expectations.

This is a family scrap book that has pretentions to be an art book and a record of the lives of a pair of gallerists, collectors and art entrepreneurs. It fails on both accounts, but as an album it does supply glimpses into the extraordinary lives and times of Kenda and Jacob Bar-Gera: Auschwitz survivors, Israeli freedom fighters against the British and the Palestinians and great supporters of many Non-Conformist artists in Soviet Russia. The sheer weight of the story, that needed to be told, wins through and the world was definitely enriched by these people and a publication was well overdue. However, if you are wanting to learn more about those artists forget it! Art is at the bottom of this book’s priorities.

Ironically, the conclusion on page 238 of this tome while summarising the need for producing this book highlights its failure. ‘Today’ it concludes, ‘almost nothing in Israel remains [to] us of this vital collection. Rivka Sum [one of their daughters] has just one single work by Sergei Shablavin in her apartment which was the artist’s gift to her. Only the exhibition catalogue, published in 2003 in English (not in Hebrew) reminds us of the fact that the Bar-Gera Museum of Persecuted Art did, in fact, exist – albeit for a short spark of time, in Israel. The book of Jacob Bar-Gera’s memoirs, published in German, Polish and Russian, still awaits its Hebrew translation and publication. Kenda Bar-Gera’s narrated memoirs were written down; the manuscript, with numerous remarks and corrections, remains in the Bar-Gera family archive and is still unpublished. The names of Kenda and Jacob Bar-Gera – two noble pioneers that accomplished the impossible for the sake of preserving cultural heritage and developing contemporary art – are not memorialized in any way either in Russia or in Israel. That is why our monographic study is not simply a book, but also a humble memorial to these unique people.’

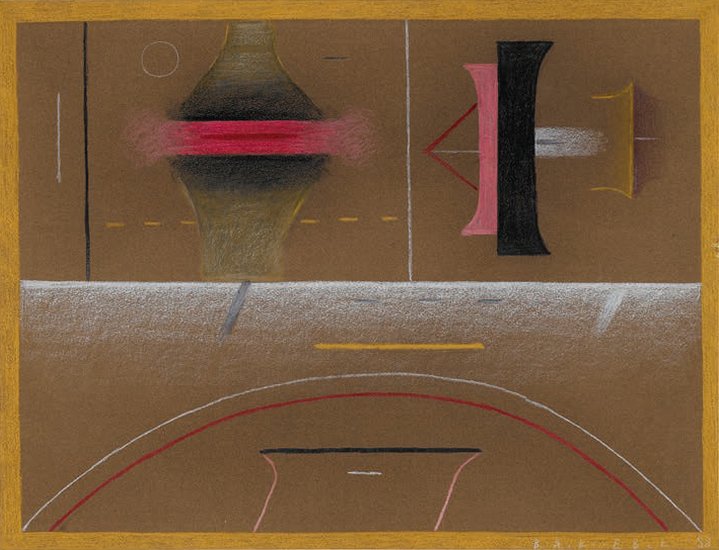

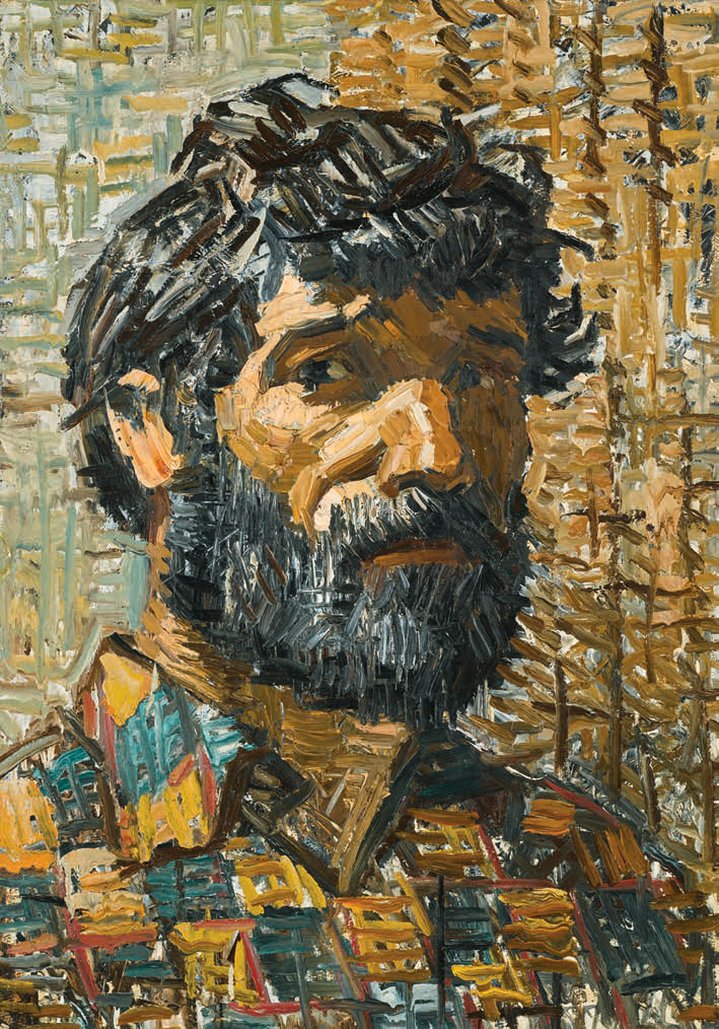

The readers that get to the end of this book are likely to feel that just as much remains hidden as has been revealed. As Kenda Bar-Gera wrote the art of this time should be known better both within and without Russia, but sadly this book is not going to change that. Just occasionally, in the catalogue section of the book that accounts for less than a quarter of the pages, the art and the artists are allowed to peep out of this graveyard presentation, almost as an afterthought.

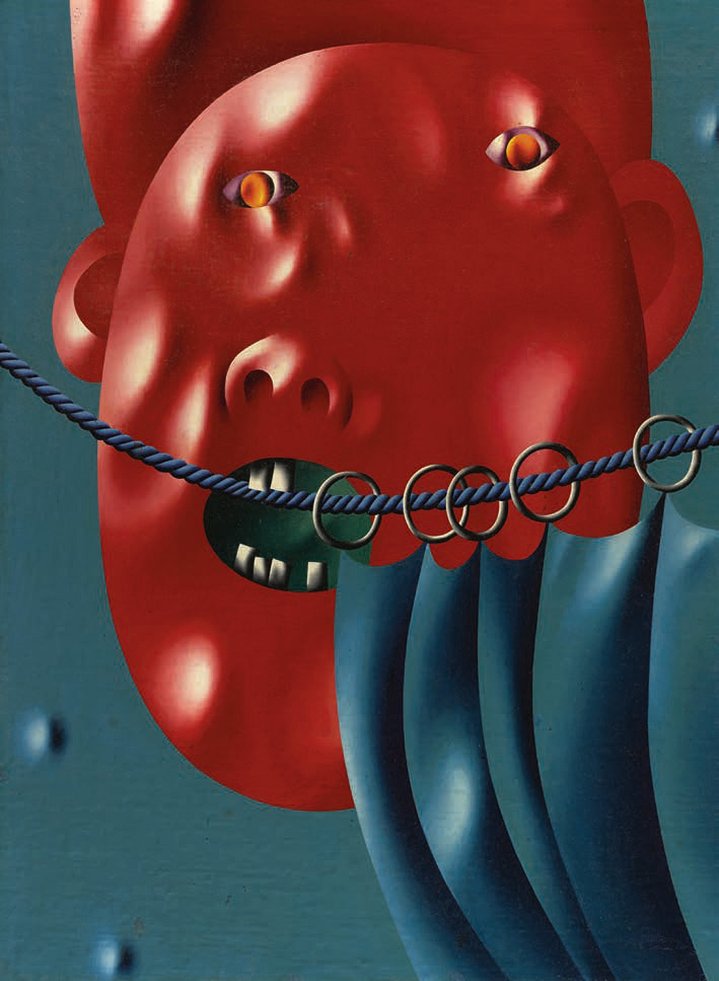

‘I accidentally tore the mask off humanity,’ Oleg Tselkov is quoted as saying before continuing, ‘We lost our faces. Or, maybe, we never had them in the first place?’ For a moment the meaning and emotion behind the mask flickers onto the pages. Oscar Rabin is also allowed to be seen struggling to emerge out of the bureaucratic expectations of how citizens of the time were meant to perceive the world.

In a resuscitated essay by Kenda Bar Gera, she acknowledges that she and her husband did not have as much money as Peter Ludwig to build a great collection. She achieved more in buying for the great Ludwig than herself. She was a vital catalyst for as she wrote: ‘Peter Ludwig was very shy when it came to meeting artists. He didn’t buy paintings directly from them, but exclusively through galleries. I knew him because he was my customer. ... Only in the last years of his life, he started to visit artists in their studios. ... For me there wasn’t any problem meeting a painter: I just grabbed a receiver, called, and introduced myself: “It’s Bar-Gera, I have a gallery. I would like to meet you and see your works.” Never was my request rejected.’

Something of Kenda Bar-Gera’s energy emanates from this album of memories. She was obviously a bit of dynamo. ‘I feel very sad when I enter galleries today, and see that the commercial element comes first,’ she wrote shortly before she died. ‘When preparing an exhibition, the question ‘what of the works will I sell?’ never occurred; I always asked: “Will the exhibition be a good one?’ I wish someone had applied this rigour to the making of this book, but also very grateful that they did actually spend so much time and effort compiling it. In these times we desperately need more books to explain what Russian artists have been fighting for over the last hundred years.