A New Book on AES+F is a Multimedia Opus Magnum

AES+F. Allegoria Sacra Knight and Death, 2012. Courtesy of the artists

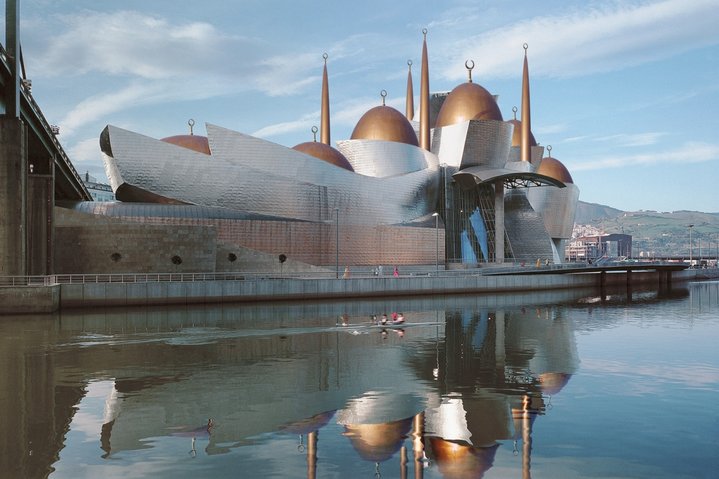

Rizzoli has published a collection of essays examining the diverse body of work by the Russian artist quartet AES+F known for surreal imaginary and a glossy visual language. Baroque and High Tech, the book is an action-packed journey into the dark side of our star-spangled world.

Art group AES+F needs no introduction. For almost four decades, Tatiana Arzamasova (b. 1955), Lev Evzovich (b. 1958), Evgeny Svyatsky (b. 1957), and Vladimir Fridkes (b. 1956) have captivated the international art world with their ultra-glossy works, subliminally capitalizing on the hidden fears of our global village. A book which ambitiously attempts to trace their entire artistic path from its outset, has recently been published by Rizzoli. Given that video art plays a leading role in the collective’s body of work, the reader quickly discovers there is more to the book than meets the eye. With instructions and a QR code, the reader can download moving images (frustratingly only accessible if you have an Apple product). The book is divided into three acts, each focusing on the productions made during a certain period of time and it strikes me as a kind of illustrated libretto of a long tragi-comic opera full of murders, battles, fights, shipwrecks, and even encounters of the third kind with aliens. It’s a reminder if we ever need one of Shakespeare’s famous lines, ‘All the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players’.

The opening of this charismatic encyclopedia of a book, however, is unexpectedly banal: ‘For decades, at least since the 1980s, the history of art has been in a nearly permanent state of tumultuous evolution. This is especially true for contemporary art history and, in fact, for the art that was being created at the time’. It does not set the tone, however, as Silvia Burini and Giuseppe Barbieri, the authors of this vapid revelation, who are responsible for most of the texts in the ‘libretto’, have chosen the safe path of quoting the artists from interviews taken through the years which act as a perfect guide for us through the book and their decades’ long artistic journey. Constantly swinging from amusement to exasperation, from fear to charm, the feeling I had upon reaching the end of the book evoked the state of mind of the wedding guest after he hears the tales of the sailor in Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner:

He went like one that hath been stunned,

And is of sense forlorn:

A sadder and a wiser man,

He rose the morrow morn.

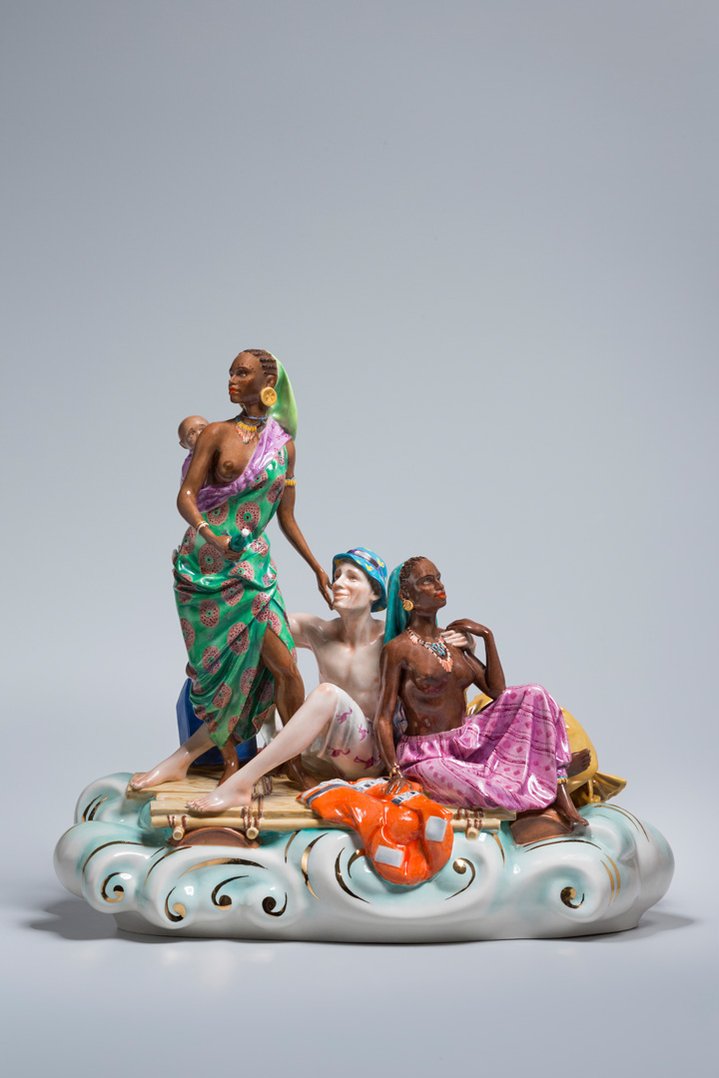

Throughout the pages, almost all of the writers remind the reader that AES+F’s ‘work has constantly been tied to the [B]aroque’, the style of the age of absolutism, which ‘functioned as propaganda, glorifying superabundance as a virtue in itself’. In today’s terms this translates as ‘oligarchy and economic inequality’. As Tina Rivers Ryan explains, AES+F’s garish carnival of the glamorous grotesque can be understood in these terms: ‘the [B]aroque is a shorthand for violence enacted on a social scale, from the ‘war’ of the sexes to race wars, class wars, and actual military wars’. Bronzino and Pontormo are mentioned as sources of inspiration for their transformation of reality into a grand media performance in their paintings. The influence of the Baroque may be substantial, but certainly not absolute. Indeed the texts relish references to many visual pleasures and narratives as direct and indirect quotations, artistic licenses, affinities, and sympathies. To extract a few: Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651), Francisco Goya’s Fight to the Death with Clubs (1820–1823), Lewis Carroll’s Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), half the filmography of Stanley Kubrick, and Mc Donald’s Happy Meals. And a special mention should go to Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy (c. 1308–1320) and Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1490–1510).

The appearance of the mutant in Last Riot Sculptures (2006) is a turning point in their work. In the mid 2000s, the artists lost interest in looking for inspiration by combing reality in all its morbid manifestations. They stopped visiting prisons (Suspects, 1997) and morgues (Defile, 2000–2007) in search of artistic material to model into an art project, and retreated in the comfort zone of the photo studio and postproduction lab to build, with the help of CGI technology, their own discomfort zone made of parallel universes cyclically stuck into a dystopian future in which humans still take the center stage, but where they are no longer alone: mutants, fantastic beasts and fantastic plants of all sorts occupy a conspicuous part of the visual paraphernalia they now build. Project after project, beautification of violence after beautification of violence, the readers get their voyeuristic and intellectual gratifications from being allowed glimpses of the horror that hides behind the sugarcoating.

It is important to say that for AES+F, the controversy in their art is never just about provocation. It is, for them, the world we live in that is sick and they are simply doing their job and representing the essence of global reality as it is. Even sensitive issues like the exploitation of underage bodies in the advertising industry are not to shock, rather to engender self-analysis. So they are not afraid to show in Action Half-Life (2003–2005) as Brooke Lynn McGowan puts it “the pedophilic visual pattern of glamorous preteen underwear models omnipresent in transnational advertising campaigns as a symptom of an ethical rupture and moral withdrawal”. At the end of the day, art is the manifestation of symptoms, not the cure.

Undoubtedly because of the huge scope and deep level of detail, the work is a much-needed research tool. It clarifies the complexity of each project, for example we find out that Last Riot (2005–2007) comprises 1 and 3 channel video installations; 10 video stills; 26 digital collages; 6 digital drawings; and 4 sculptures, aluminum cast in white enamel. This valuable information helps to navigate their conspicuous body of work which dates back to the early 1990s. However, perhaps because of this microscopic focus and sheer breadth, there are confusions, such as Hou Hanrau in his essay mistaking the work made for the 2019 opera Turandot with the 2020 Turandot 2070 (1-channel, 3-channel, and 8-channel video installations; series of stills; series of three 1-channel videos with custom code on blockchain), a project, the artists explain which is “based on the video material prepared for the representation of the opera, but at the same time conspicuously independent”.

Following chronology alone, Turandot 2070 is the last project to date. However, the book's visual trip for the reader does not end here. There is a picture made from words in computer graphics and pigment print on a banner from their 1995 Berlin Wall 2, New, Nice, and Improved. It’s a prayer to God that might serve as a chant for all the other works in the book:

Lord!

Divide the poor from the rich,

The South from the North,

The healthy from the sick,

The West from the East,

The civilized from the wild.

However, there is one thing that no invocation to God could do: divide the murderer from the victim in the reader of this book. As readers, we are inevitably both.

AES+F. Text by Giuseppe Barbieri and Silvia Burini. With contributions by Tina R. Ryan and Brooke L. McGowan, Tom Morton and Hou Hanru. 2023

New York, USA