A hidden haven for art

A Moscow exhibition tells the story of APTART, an artistic movement that managed to turn a private flat into a hub for uncensored cultural activities a few years before Perestroika changed the fate of the Soviet Union.

The lives of artists seem to have always fascinated those watching from the outside. Their habits, quirks, personal traumas: all might be clues to the source of their creative drive. Yet most encounters with artists happen at a distance through their artworks. Far less often do they come within close reach. The Soviet era collective project APTART is one such exception. Its name is a contraction of “apartment art” and it refers to a series of artist-organized gatherings which took place between 1982 and 1984, both outdoors and in the apartment of artist Nikita Alexeev (b. 1953). That short yet prolific experiment, as well as the participating artists’ subsequent solo careers, are the focus of ‘Remembering APTART’, on display at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art through April 5.

APTART was one of the last so-called “anti-shows”. Inevitably, it ended badly with the KGB’s violent confiscation of the artworks on display in February 1983. However, a fresh wind was blowing, due to Gorbachev’s “Perestroika” in 1985. New travel opportunities arose, matched by a burgeoning interest in publications by Russian and Western scholars about those artists’ work.

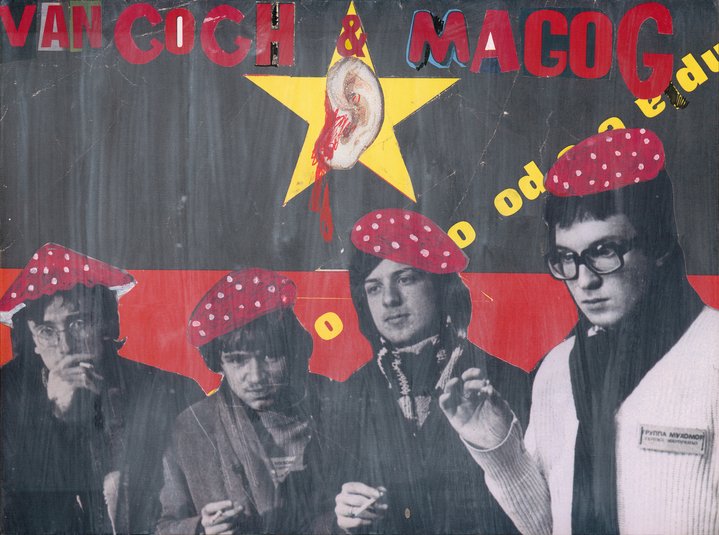

Since the early 1970s in Soviet Russia, some artists had sought to create a space free of the tightly regulated official art system still bound to the sanctioned style of Socialist Realism. Nevertheless, Alexeev recently described APTART as a world “parallel” to rather than “opposed” to the then dominant system. The priority, he said, was “a place where we could work and exist and communicate”. APTART’s leading participants included Alexeev, Georgy Kiesewalter (b. 1955), Andrei Monastyrski (b. 1949), Vladimir and Sergey Mironenko (both born in 1959), Vadim Zakharov (b.1959), Yuri Albert (b. 1959), Victor Skersis (b. 1956), Andrei Filippov (b. 1959), Konstantin Zvezdochetov (b. 1958), Larisa Rezun-Zvezdochotova (b. 1958). They sought to distinguish themselves from a prior generation of alternatives, the Moscow Conceptualists. If many of the Conceptualists, such as Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933), Erik Bulatov (b. 1933), and Komar and Melamid (b. 1943 and 1945), had been seen as sympathetic to APTART, by the early 1980s artists like Alexeev and Kiesewalter had come to perceive them as increasingly esoteric and exclusionary. APTART-ists took up a junk aesthetic, deliberately low-key and homely. Think of the group called ‘Mukhomors’ (“Toadstools”), which consisted of Mironenkos, Zvezdochetov, Aleksei Kamenskii, and Sven Gundlakh (b. 1959). They took over Alexeev’s fridge, painted a title page on the door, added the written plot to boxes next to the food and drink, and called it Novel-Refrigerator.

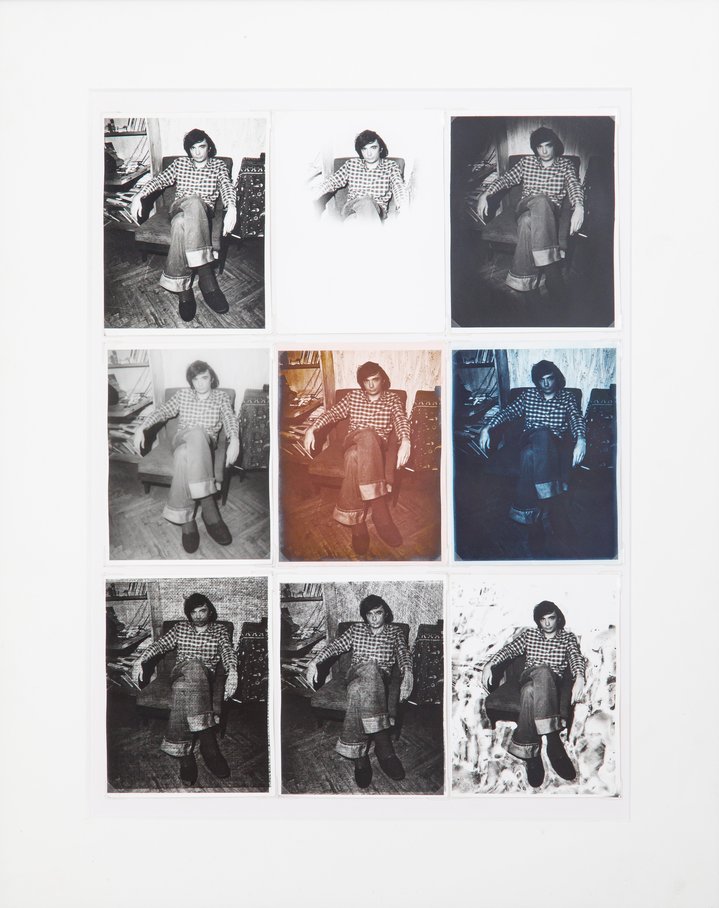

Looking at the typed and handwritten invitations to events; the roughly hewn, painted boards, canvases, and banners; the intimate black-and-white photographs of friends and colleagues while they lounged, sipped tea, and engaged in debate, I had the feeling of being near someone. The fight to carve out an intimate and personal space for their practices was the art itself. The presence of the personal was especially overwhelming in Kiesewalter’s snapshot series of Monastyrski reclining in an armchair. Kiesewalter’s photographs have done much to create a reality of APTART after the fact, although he said that his aim was initially more about being at the event than documenting it. “In the 1970s, I had absolutely no thoughts of preserving anything for posterity. I shot our life, in which photography played a part,” he explained.

Physical space was both an asset and a liability for APTART. A map of their 1983 en plein air anti-show, drawn by hand on paper, locates and describes the works using tiny labels and icons.

To create an alternative space, as well as to remain one, a group must be nomadic. Projects like APTART, which responded to a particular condition, lose their sense if they are created to last forever. And while their work can handily evoke the 1980s, the era of those spontaneous art actions and their work after the Soviet Union’s collapse demonstrates that gaining a platform while maintaining a provocative stride is much harder.