A Heavyweight of Art Criticism. In Memory of Andrei Kovalev

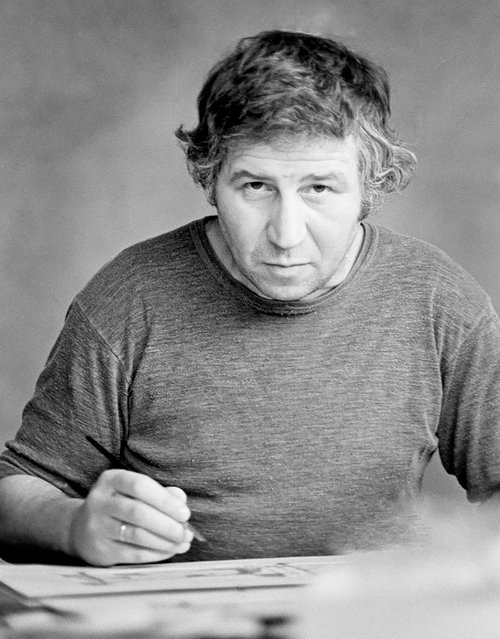

Portrait of Andrei Kovalev. Courtesy of Garage Museum of Contemporary Art and Russian Art Archive

One of the most talented and well-respected art scholars and critics Andrei Kovalev has passed away in Moscow at the age of 66. He often jokingly referred to himself as ‘the weightiest critic’. Having penned many articles and books on contemporary Russian art he deserves this accolade in all seriousness. Editor-in-Chief of the Art Newspaper Russia, Milena Orlova, pays personal tribute to her late friend and colleague.

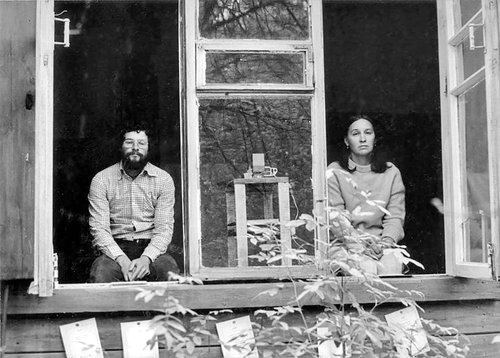

The title of ‘the weightiest’ stuck to Andrei Kovalev after the following event. Back in 1992, in a gallery in Trekhprudny Pereulok in Moscow which was run by artists who lived there, an action called ´Heirarchy in Art´ by Alexander Sigutin (b. 1959) took place, designed to find objective criteria for concepts like ‘creative growth’ and ‘social weight’. The heights of artists were measured with a ruler, and art critics were weighed and Andrei Kovalev won the competition for the critics. (Not only a willing participant in art actions, he once came up with an exhibition in which Duchamp's urinal, a ready-made called ‘Fountain’, returned to its everyday life: a functioning urinal was installed in the gallery, and the action was called ‘Not a Fountain’).

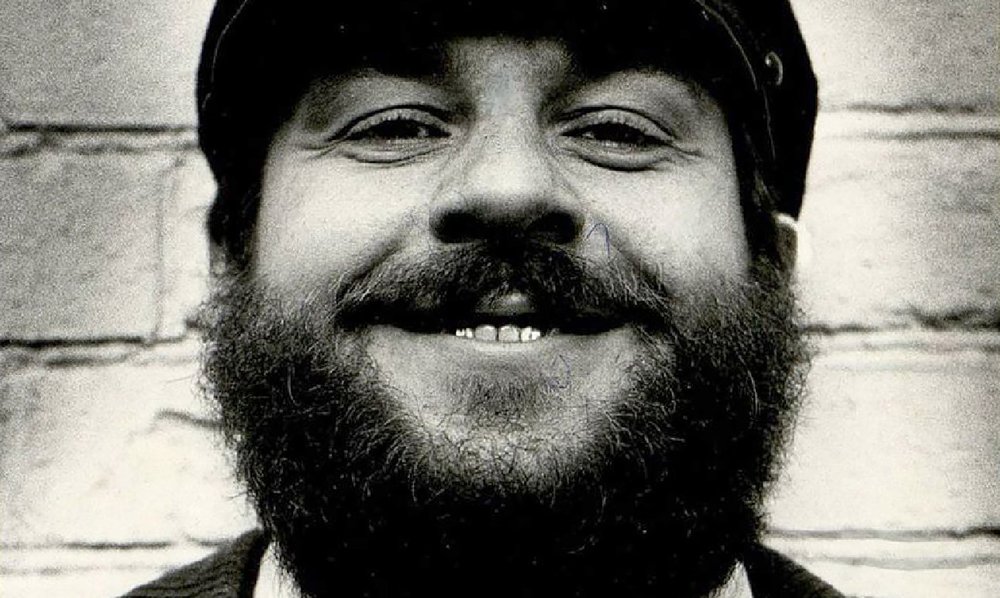

It must be said that this large man, who was often seen sporting a T-shirt with a self-portrait of a dishevelled and surprised young Rembrandt, to whom he was remarkably similar, was already an authority by this time. Both in the academic environment (having graduated from the Department of Art History at Moscow State University, in the 1980s he published in professional journals, and in the 1990s he defended his PhD on Soviet criticism of the 1920s at the Institute of Art History in Moscow) and, more importantly, he was already an influential critic whose articles were published in newspapers, not only in specialist academic publications on art history. In fact, Andrei Kovalev defined himself as the first post-Soviet newspaper art critic. He reached his peak in this field when he was working in the forward-looking cultural section of the newspaper Segodnya (Today), as well as cooperating with many other publications, writing in the first issue of Viktor Misiano's Art Journal, and contributing to Artchronika, Vedomosti, Izvestiya, Ogonyok, and later The Art Newspaper Russia.

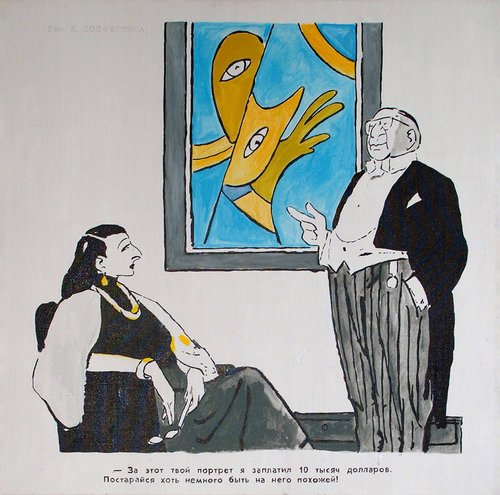

Writing of his recollections of the free spirit of the 1990s in the introduction of one of his books he said: ‘No boundaries were set for the Culture department (at Segodnya) – and we had a lot of fun, talking to our readers as if they were old friends who could be mystified and overintellectualized on topics only we could understand. I, for example, bragged in a capitalist newspaper about my decorative Marxism; Vyacheslav Kuritsyn disseminated Postmodernism everywhere’. One of Andrei Kovalev's most memorable, critical masterpieces was an article in Segodnya about Ilya Kabakov (1933-2023), where he used a psychoanalytical approach: the figure of the great conceptualist was seen as part of an oedipal complex that made new generations trample on their artistic ‘father’. Kabakov himself did not much like this criticism of him, but according to Andrei Kovalev's own beliefs, polemics were necessary for a healthy artistic environment. ‘As it was clear to me from my studies in archives, a true critic has to be biased. And I am still convinced that moments of aggressive and unrestrained polemics between currents and directions accurately index the situation of the Golden Age.’

In general, analysis and interpretation was Kovalev's sweet spot, but in the 2000s there was an increased standardisation in the media, when it became more important to provide information to readers than to produce excesses of criticism, and a kind of bland congeniality became de rigueur vis-à-vis art. Andrei Kovalev returned to academia, taught at Moscow State University, and published several books, including ‘Name Index’ and ‘Critical Days. 68 Introductions to Contemporary Art’. One of his most significant works was the book ‘Russian Actionism. 1990-2000’, a deep-reaching, fundamental study that compiled documentation of the most radical and ephemeral trend of the 1990s. In 2008 he received the State Prize for Contemporary Art ‘Innovation’ in the section ‘Theory, Criticism, Art History’ for this weighty tome.

Ultimately, Andrei Kovalev's dream was to create not just one book about one, albeit important, movement, but a universal history of art of the post-Soviet period. Following the example of artist and art historian Igor Grabar (1871-1960), who oversaw and produced a multi-volume textbook with a team of writers, Andrei Kovalev aimed to realise a similar project with selected colleagues which resulted in a book published in 2021, ‘Unfinished History. Contemporary Art in Faces’ (2021), a collection of articles, characterised by lively and easy language, about 50 contemporary Russian artists. He wrote eighteen articles in it. But the scope of Kovalev’s interest was wide and he also wrote about Mikhail Larionov (1881-1964) for the Tretyakov Gallery’s Lavrus project and was no stranger to writing for publications far removed from art life to broadcast his own thoughts and ideas to the widest circle. And in totality he created his own, honest and ironic, ‘Kovalev's’ history of Russian art.

This article was first published in Russian on the website of The Art Newspaper Russia on 13 September 2024.