A Cryptic Reading of Zhilyaev’s ‘n Haus’

_n Haus. Arsen Zhilyaev. Exhibition view. London, 2025. Courtesy of Pushkin House

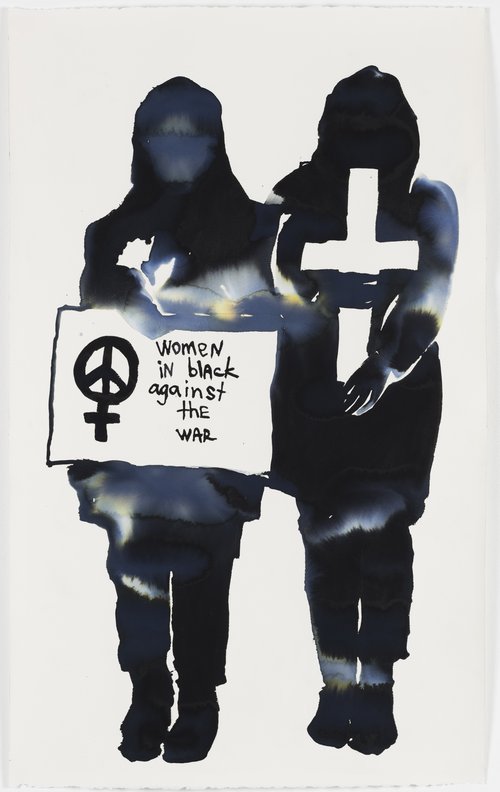

A new total installation by Arseny Zhilyaev on view at Pushkin House in London explores the politics of time, where the Russian avant-garde meets fascism and a retelling of 20th century history makes us think about our own complex and vulnerable present realities.

The soviets politicised leisure time and this was communicated among other channels through art – paintings of Soviet citizens celebrating national holidays, critiqued with delicious irony in Ilya Kabakov’s famous 1987 Holiday Series. The Soviet underground artists themselves turned this political control of time on its head by using their ‘free’ time to work as professional artists, outside any market economy or institutional recognition. The politics of memory is a field of research which is even more important today than ever before, because of the mass of information posted online, which is taken up by AI and will shape how we later digest facts, there is a scramble for all of us to write history, we are all actors in this not just presidents and prime ministers. An example of how time can be manipulated by an actor, in this case the son of a mother who is in a coma, is the 2003 film ‘Goodbye Lenin!’ where the dutiful son recreates a world where a Socialist East Germany still exists around his mother in order to protect her from deep emotional shock and trauma.

Russian national ideologies behind the current Russian-Ukrainian crisis which developed into Russia storming Ukraine on an unprecedented scale in February of 2022 can be traced to what is by now a well circulated essay that Vladimir Putin published in 2021 titled Ón the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’ which sets out his vision. It is a worldview at odds with most of the international community and its hitherto accepted norms, legitimizing what the international community saw as the invasion of an independent, sovereign nation. Putin, in part using the politics of time justifies his actions in the present.

An exhibition by Arseny Zhilyaev (b. 1984) at Pushkin House in London is a timely exploration of the politics of time. Zhilyaev has long been interested in the cross pollination of politics of time and art and culture, especially with regards to museology. And here at Pushkin House his total installation characteristically involves a critical intervention with this institution itself. It is interesting and relevant because over the past few years there has been much soul searching among Russian cultural intellectual elites about Alexander Pushkin and whether there are darker sides to his deification than meet the eye. An institution like Pushkin House itself has to now navigate very complex and potentially incendiary subjects as it educates and promotes Russian culture in the present.

The politics of time allow you to revisit the past and imagine a different present, or to become a lobbyist or activist to bring about a different future. At the centre of Zhilyaev’s work is a silent 16mm black and white film, which I settled down to listen to alone in what is the music room at Pushkin House, a lovely Georgian dual aspect room from which you can see the tops of trees and the occasional red London bus as it purrs by. Here, sipping my coffee, listening to the rhythmic sound of the spool mechanics rotating serves as a constant reminder to me that what I am watching is about the past … but nothing that Zhilyaev makes or writes about is really about the past, rather he holds a mirror up to us in the present and mostly his work gets us to think more deeply about our socio-political realities.

Zhilyaev has always been interested in the Russian avant-garde, I first saw his ‘Time is Working on Kommunism’ installation back in 2010 and his calligraphic wall mounted wooden sculptural reliefs with stylised avant-garde fonts exaggerated to become almost cryptic. His current total installation at Pushkin House is also very cryptic, an extended part of the silent film is subtitled in German (thankfully I was a Germanist as well as a Slavist at university) and so for the unsuspecting viewer after what must feel like an endurance you might reach the end of it without falling asleep. The strange title ‘_n Haus’ is hardly eye catching but later you discover it is a deconstruction and erasure of the word Pushkin, a fusion of pushki, the Russian word for cannons, and German for House. The title then becomes a clear signpost to an emotional reading of the whole piece, dark, haunting and aggressive.

The present here is politicised through the past in what I see as a kind of parallel yet opposing mirror to Russia’s contemporary politics of selecting the past to create the future. Here Zhilyaev employs the iconic anti-war avant-garde film ‘Meat-grinder number 1’ directed by Alexander Razymovsky and Klimenty Mints which was shown at a gathering of the OBERIU collective in 1928 and later disappeared, a nuance on which to reflect further as it also underlines a key theme of this work, that of cancelling culture. Back in the 1930s the Bolsheviks cancelled the avant-garde in a brutal, systematic way in what became a wider repression of freedom of expression at large where the manipulation of art served political power reminding me that in general we must be very mindful when we witness any cancel culture in operation. Watching the film I see grainy images of train carriages, repeated over and over again, with echoes of ‘Echelon’, an iconic 2006 video animation by the Russian art collective ‘The Blue Soup’. I can only guess at where the trains are going or coming from, such images of carriages are deeply disturbing and confusing, etched on our collective memories as metaphors for forced exile, imprisonment or perhaps the human beings packed inside are being sent to the front? This work is ostensibly a retelling of the outcome of the great patriotic war (as it is called in Russia) where here in Zhilyaev’s imagination it was won by the other side, and Fascists take over and dismantle Russia and its culture and language. The sting in the tail is that this work was created both by Zhilyaev and AI – which actor among them both actually determined this hallucinatory outcome of the war? With Zhilyaev the cryptic is often at the centre of his fascinating poetics.