Pomidor Art Group. From the project SPEECH(LESS). Courtesy of the artists

Why Artists Unfurl Their Banners

Young artist duo Pomidor exhibit hand-embroidered banners with stories of Russian political prisoners at London’s Not For Sale Gallery. But they are not the first artists to use this medium in unexpected and often provocative ways.

Every banner is a statement, whether or not there are words on it. The message is usually clear, concise and needs no explanation. It is often a call to action. It urges soldiers to attack and shoppers to buy discounted goods – while stocks last. This is probably why artists make flags and banners their medium. The temptation to add new layers of meaning to such an emotionally charged object is almost irresistible. The texture of the fabric, warm and smooth to the touch, adds to its allure. Artists manage to turn a call to arms into food for thought, to make an object designed to inspire enthusiasm into one that inspires doubt.

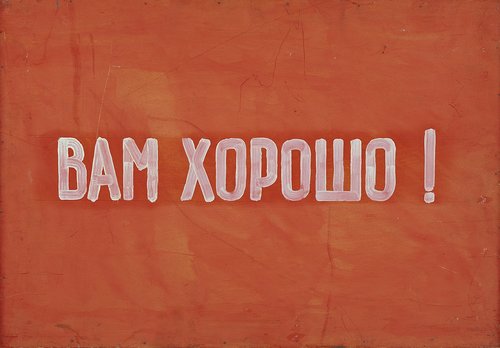

Banners are a favourite tool of propaganda, overused to the point where their message becomes hollow and worn. In the Soviet Union they became dull decoration, bold splashes of red on drab, colourless streets, bearing meaningless slogans such as ‘Glory to the Communist Party’ or ‘Five-Year Plan in Four Years’. The underground artists of Moscow Romantic Conceptualism often mocked their blandness. The Collective Actions group ventured into the woods and fields around Moscow with banners that looked legitimate from a distance. Their first such action was called Slogan-1977. A long piece of red cloth measuring one by ten metres was hung between two trees on a hill. Inscribed with white stencilled capital letters it read: “I DO NOT COMPLAIN ABOUT ANYTHING AND I ALMOST LIKE IT HERE, ALTHOUGH I HAVE NEVER BEEN HERE BEFORE AND KNOW NOTHING ABOUT THIS PLACE”. This was a quote from the book ‘Nothing Happens’ by one of the group’s founders, Andrei Monastyrski (b. 1949).

Artists used the visual language of propaganda, taking its absurdity to the extreme to create a Zen-like paradox.

In the immediate post-Soviet period, Novosibirsk artist Artyom Loskutov (b. 1986) and his art group CAT (Contemporary Art Terrorism) brought political and artistic currents of the absurd together. Since 2004, each year they have been organising May Day (Labour Day in the USSR and today’s Russia) processions called Monstraziya, whose participants carry absurd slogans such as “God, forgive us!” They have often surreptitiously joined local communist groups with their red banners, who since the Soviet time still march through the streets on that day. Their idea became so popular that it spread from Novosibirsk to other large cities across the country.

Chto Delat’ (What is to be done?), a collective of artists, activists and philosophers founded in St Petersburg and now scattered across several countries, launched a series of artworks called ‘Learning Flags’ in 2011. These intricate textile collages, bearing provocative slogans such as “Hunger, Anger, Joy”, were designed to serve a dual purpose – as works of art and as banners to be carried at protest rallies and demonstrations. Unlike ‘Monstraziya’, with its light-hearted performative vibe and slogans painted on random sheets of cardboard, the ‘Learning Flags’ were made to last, with future museum exhibitions and gallery sales in mind.

Some artists create banners and flags without slogans, believing that, in some contexts, silence can speak louder than words. Once, during the ‘Nomadic Museum’ action in 2012, at the height of the street protests in Moscow triggered by the parliamentary and presidential elections, a group of artists presented their works by rolling them along the city’s boulevards in carts in a moving exhibition curated by Yuri Samodurov and Andrei Mitenyov. Artists Maria Arendt (b. 1968), Natalia Arendt (b. 1959) and Margarita Novikova (b. 1962) joined the procession with a group of friends and supporters, carrying flags sewn from transparent fabric. In a political climate where many criticized the recent elections as being rigged, the project reflected Russian society's urge for transparency. In 2021, artist Alexander Rumyantsev anticipated the current trend for harmless, visually appealing, apolitical art with his project ‘Flags That We Need’. He noticed that some of his landscape photographs resembled flags, as the earth and sky on them stretched out in parallel horizontal stripes of an almost uniform colour. He decided to print these photographs on banners, transforming them into flags suitable for the utopian world without national pride and borders.

The banner’s power to attract attention can also be its downside, sometimes getting its creators into trouble. On June 12, 2022 (a national holiday called Russia’s Day), a banner reading “Today is not my day” appeared on the embankment of the Moskva River in Moscow, directly in front of the headquarters of the Ministry of Defence. Artists and activists Anton Malgazhdarov and Denis Mustafin, who carried out this action, were sentenced to 15 days in prison.

Two years later, such artistic interventions are hardly possible in Russia due to tightened legislation. However, artists who left the country after the outbreak of the armed conflict with Ukraine are still able to raise their banners abroad. Pomidor Art Group, an emigrated artist duo from Russia who moved to the UK in 2022, are working on their project SPEECH(LESS), dedicated to political prisoners in the country. “LESS is in brackets because many brave people in Russia are not silent and continue to fight,” the artists explain. In keeping with the current vogue for textiles and handicrafts in contemporary art, they have embroidered the prisoners’ portraits and stories on banners that could be hung out of windows.

The aim of the project is to inform Western society about what is happening in the country. “Russia is not an isolated island somewhere far away and not a separate planet. Two years ago it became clear that everything happening in the country extends its borders and affects the entire world,” the artists point out. They are lending their works to friends and acquaintances who have agreed to display them in their windows for passers-by to read and reflect on. This unusual medium could attract the attention of victims of information overdose, who have become almost immune to the horror stories, true and false, that are constantly being disseminated by numerous digital sources. Since the duo emigrated from Russia in 2022, the project has been shown in America, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Canada. It can be seen in London until 30 September 2024.