Vladimir Yashke’s Drawings from a Psychiatric Ward

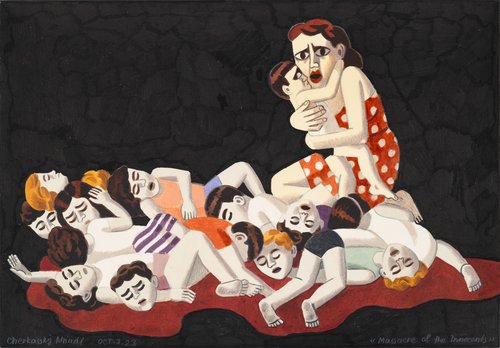

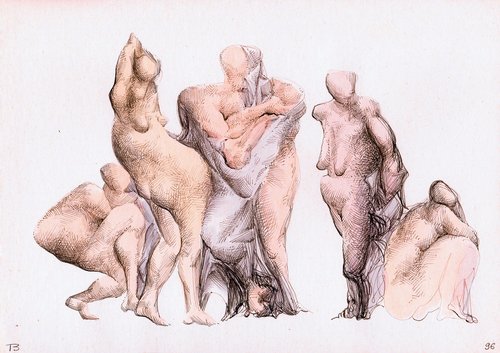

Vladimir Yashke. Drawings from a Dead House. Courtesy of Matiss Club Gallery

A new book and exhibition, ‘Drawings from a Dead House’, celebrate an idiosyncratic St Petersburg artist who throughout his life suffered from stigma and exclusion.

The work of St Petersburg artist Vladimir Yashke (1948–2018) was a reincarnation of the art of the Parisian school of the 1920s and early 1930s - half a century later, in Soviet Russia. Recently, two exhibitions in St Petersburg have brought to light some of his early drawings made in the 1970s within high security psychiatric hospitals.

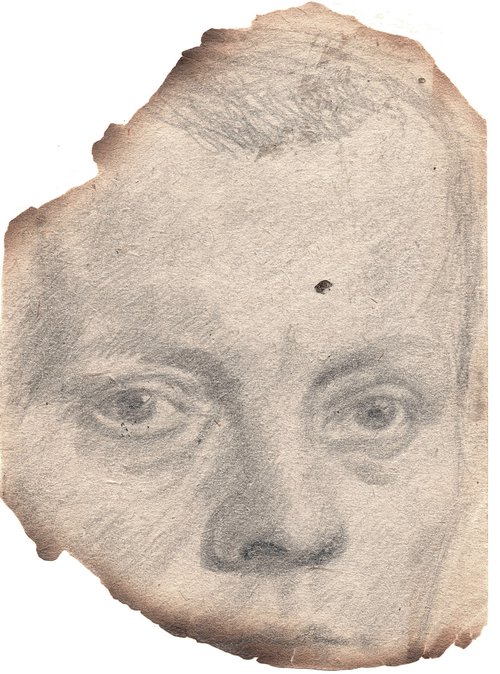

Yashke was born in Vladivostok, his father was a naval officer who, for an alleged misdemeanor, was sent from Leningrad to the Far East. Later, the family moved to Sevastopol, the main base of the Soviet fleet in the Crimea, where in the mid 1960s Yashke studied at art school. In 1966, Yashke enrolled at the Moscow Polygraphic Institute and studied art focussing on book design, until he was forced by events to leave the institute in 1972. The year before he had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, admitted to a psychiatric hospital ostensibly at the request of his fiancée's parents who were against their daughter ‘from a good Moscow’ family marrying an art student from the provinces. During the Soviet times, psychiatry was part of a punitive system, something which has never quite disappeared in Russia, a negative experience to punish rather than heal patients. What happened there broke Yashke, he was severely beaten numerous times and by his late twenties he was permanently disabled.

Without this extraordinary experience, it is hard to know how his art would have evolved, and even how his life might have turned out. For years Yashke changed many places and occupations, not sticking at anything, he worked as a graphic designer, loader, sailor, lifeguard, mountain tourism instructor, surveyor, stoker, art student’s model, watchman among others. Finally, in 1976 Yashke settled in Leningrad (St. Petersburg), and a few years later he began to take part in underground art exhibitions. It was around 1984-85 that his mature period of creativity began when he joined the Mitki art group whose popularity in the underground was at its peak. They referred to Yashke as the ‘grandfather’.

By then the artist had chosen his path, remaining ever since faithful to the art of the French Impressionists, Post-Impressionists and the Nabis. For him contemporary relevance was not a concern at all, even though today with hindsight his work speaks of the era in which it was created. In Soviet Russia the prohibition of any ‘formalism’ at all led to the emergence of artists who were zealots for ‘pure art’. Over many years, Yashke's art – painting and drawing, poetry and prose – did not evolve significantly but in some ways became more solid, echoing the great masters of the past who were his heros, especially Chaim Soutine (1893–1943) and Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), but also others such as Paul Cezanne (1839–1906), Honoré Daumier (1808-1879), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) and the Russian Mikhail Larionov (1881-1964). Another non-conformist working in St Petersburg also in the 1960s and 70s, Solomon Rossin (a pseudonym of Albert Rozin (b.1937) who now lives and works in France) was a spiritual companion, with a similar aesthetic.

Zinaida Morkovkina features dominantly in Yashke’s art, she is the heroine in many of his paintings and poems, the artist’s muse. Morkovkina means carrot in Russian, suggestive of not only the colour of her fiery red hair, but there is also unambiguous phallic connotations.

A decade ago, to mark the artist’s 65th birthday, the Russian Museum held a solo retrospective called ‘Personal Paradise’, with most of the works having been lent from private collections, including Moscow collector and restaurateur Dmitry Pinsky.

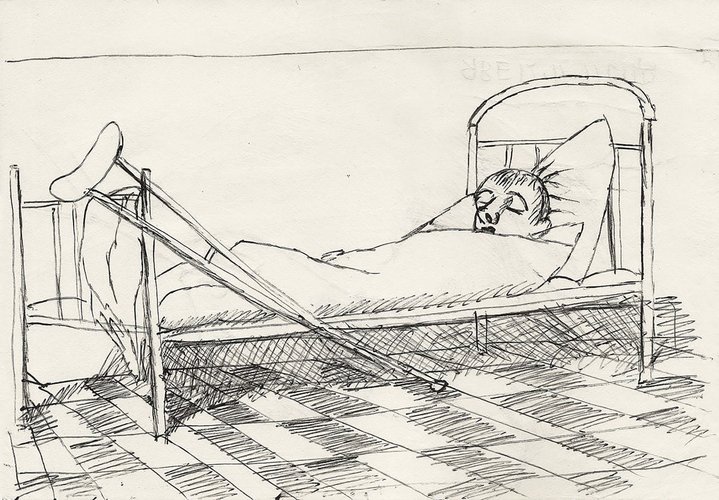

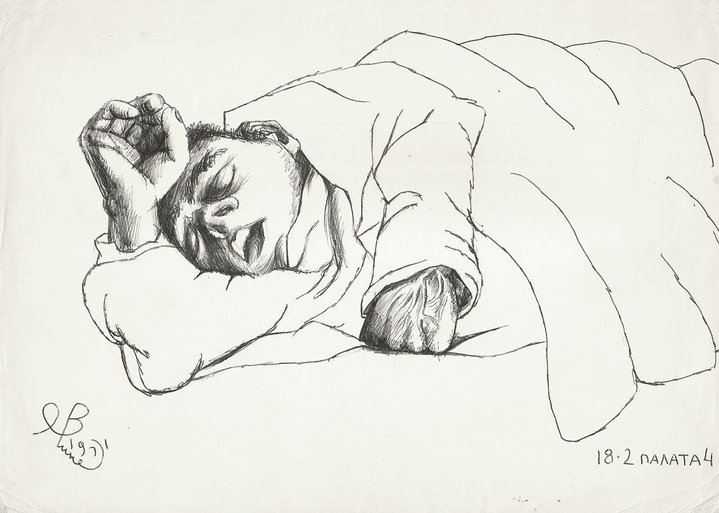

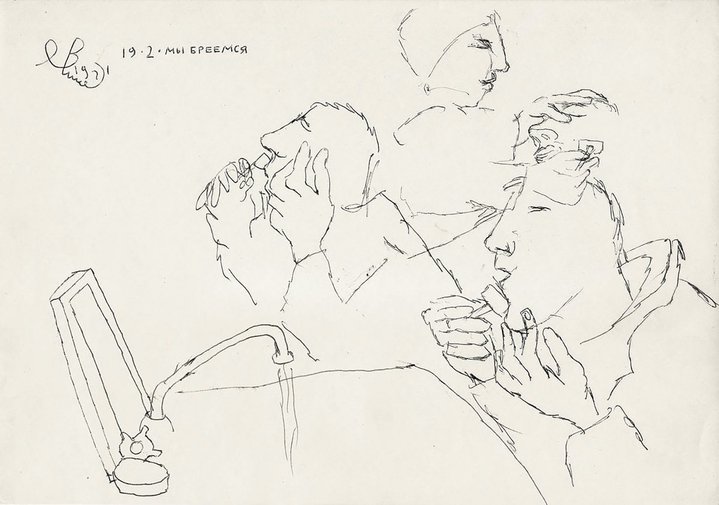

The album ‘100 Drawings from a Dead House’, published by Boris Faizullin and Alexei Rodionov both collectors from St Petersburg and admirers of Yashke’s art, and the accompanying exhibition, chart a defining episode in the artist's biography with candour. Until today, Yashke’s hospital drawings have been exhibited only in very small quantities, however in this new book you find one hundred drawings from the approximately three hundred that are known to have been made during those dark years in the artist’s life.

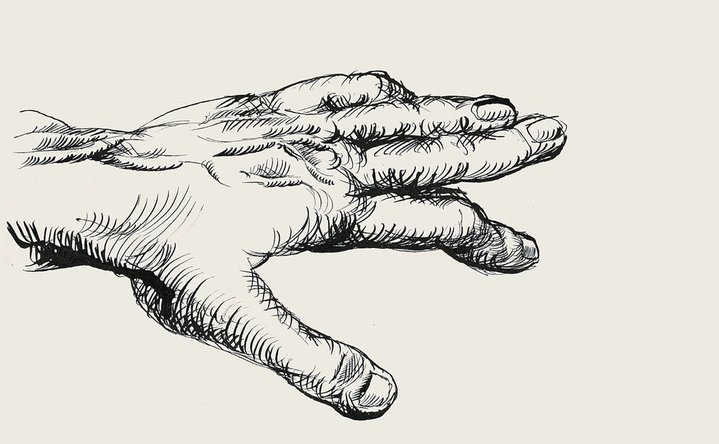

The publication of this book and the inclusion of Yashke’s drawings from the psychiatric hospital into his body of known work add a new interpretation to his art: references to Foucault's ‘The Birth of the Clinic’ and ‘The History of Madness’. There is nothing specific in these works that suggest they should be seen as art brut, they are simply the drawings of a young artist starting his career and finding himself in very difficult circumstances. In the repressive hospital conditions, he found an outlet in constant drawing. The plasticity of these works recalls Matisse’s late works on paper, similar forms made by touches, rounded lines and cloud-like arcs.

In later years, Yashke often found himself hospitalised in mental institutions and the system was set up in such a way that the diagnosis itself became a stigma and once you were a patient, you were officially registered and forced to go back regularly. In his own diary writings in 1981, the artist wrote: “I am not a fanatic, but looking back, I realise that in my selfless service to drawing there was something of fanaticism present there … I could not have endured it otherwise”.

The interest today shown by the public in these early drawings by Yashke coincides with a much wider, global interest in the artistic practices of individuals who are seen as outsiders and communities on the periphery. It is not strictly speaking contemporary art, as it is currently defined, yet it is art with such power and depth, that is can carry any contemporary interpretations.

Vladimir Yashke. Drawings from a Dead House

St. Petersburg, Russia

17 April – 8 May, 2024