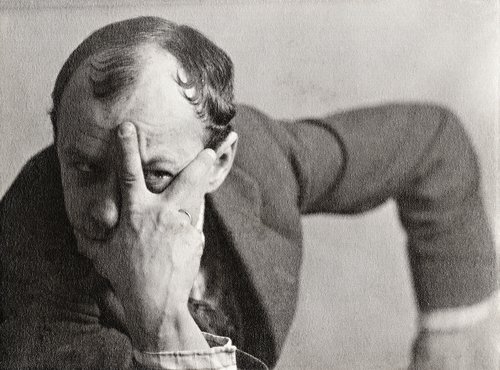

Weisberg’s Drawings. Exhibition view. Photo by Dmitri Chuntul

Vladimir Weisberg’s colourful white

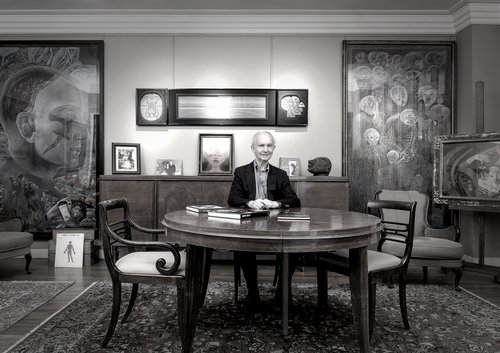

In Artibus Foundation in Moscow opened its new season with an exhibition of graphic works by Vladimir Weisberg from the collections of Inna Bazhenova and Elena Khlopina. This is the artist's third exhibition at the Foundation since 2014. Forthcoming this October is a complete catalogue of Weisberg's work at the State Pushkin Museum, prepared in collaboration with In Artibus.

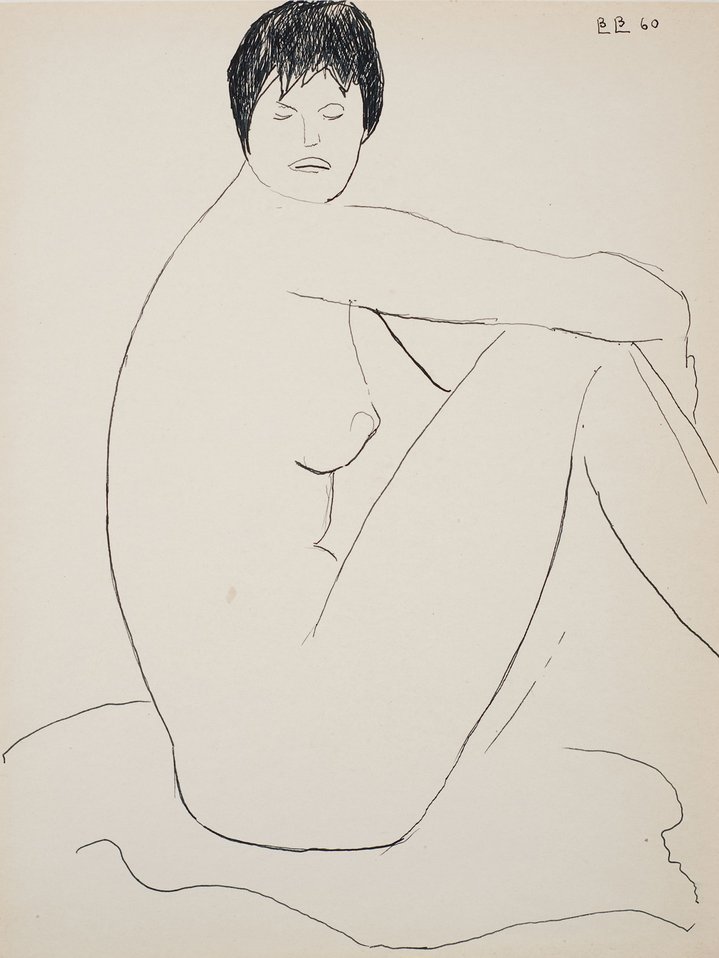

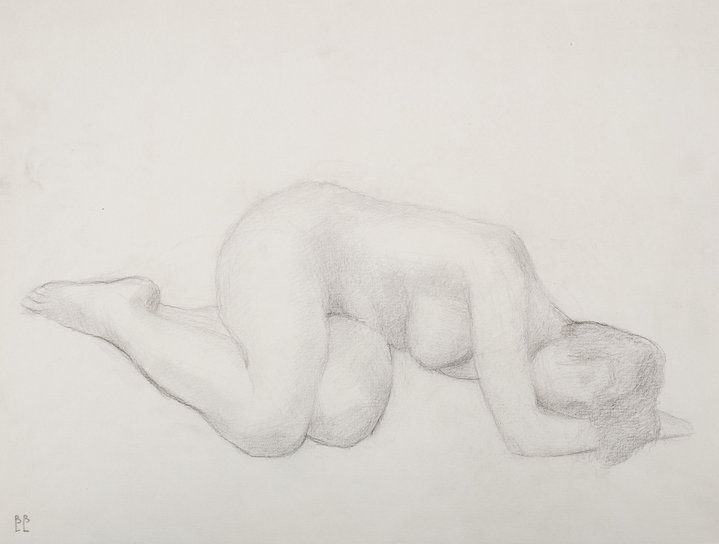

‘When I paint the nude, I think of cubes, and when I paint cubes, I think of the nude,’ Vladimir Weisberg (1924–1985) once explained. Making up the majority of the works in the new exhibition, these words describe his approach to nudes well. This connoisseur's exhibition project for afficionados of works on paper shows off an otherwise little-known side of his talent.

Technique and composition were of more interest to the artist than the model. In one place he is concerned with the bold, changing line of ink that marks the border of the body and the edge of the blanket on which it rests. In another, a fine, constant roller line forming a fine grid of fine loops overlapping each other where the shadow is formed by the density of the grid, the light by the field of white, and the woman only serves as a pretext for exploring these graphic relationships. In the third, he sketches the outline of the figure in brown watercolour pencil and fills it with blurred patches of red watercolour, changing the density to indicate different volumes.

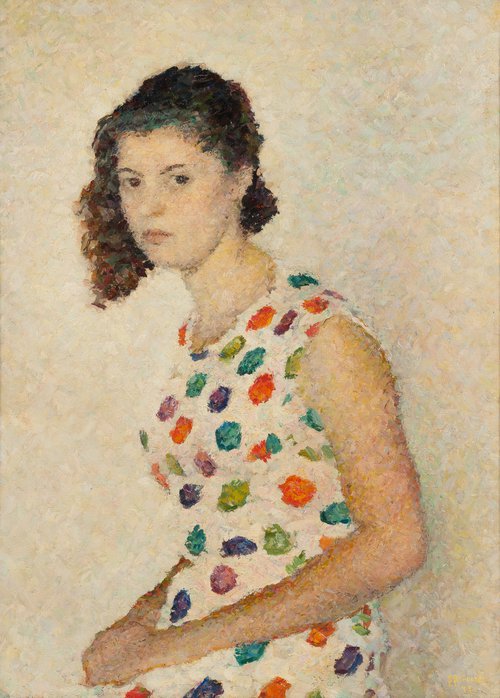

Weisberg’s watercolours occupy a particularly special place in his oeuvre. They convey the shifting, vibrating undertones of the human skin, its warmth, the breath of flesh dissolved in an airy, light environment, as in the five nudes from Inna Bazhenova’s collection from the 1970s, where the actual bodily colour is mixed with tones of either the rising or setting sun, in typical Moscow bluish-pink tones. The subtlety of the halftones makes Weisberg one of the best watercolourists of non-conformism. His keen perception of the effects of balancing hues and his work with gradations of complementary colours bring his watercolours closer to his paintings.

Vladimir Weisberg was a Soviet artist who created a paraphrase of American minimalism in the language of Seurat and Cézanne. He understood minimalism not as working with pure material, pure colour, pure form, or even more so with pure ideas, but as limiting of form with a complication of colour. Since the sixties, Weisberg worked with white.

He is known for his concept of ‘white on white’. But Weisberg's white is very different from that of Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) or Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956). His ‘white on white’ involves a convergence of colour relations, to the point where the figure is separated from the background, but both are read as painted in the same colour, white, which at the same time contains a multitude of possible half-tones, complex in their mutual play. This gives his painting that sense of weightless lightness that reproductions struggle to convey. He paints air with objects and bodies, not the other way round.

During his lifetime, Vladimir Weisberg was a poster child for ‘silent painting’. In the Soviet Union during the Brezhnev era, there was a conflict between ‘loud’ painting – official, ceremonial and ideological – and ‘silent’ painting. Since all the official positions were occupied by the artists who painted ‘loudly’ painting ‘quietly’ already by default looked like a political posture: not striding in line.

The ‘quiet ones’ learned from the dead French. The orientation towards Monet and Seurat, which would have looked provincial salon in their homeland in the fifties of the 20th century, seemed alarmingly modern in Moscow. For Weisberg, only painting that came no later than that of Georges Braque was relevant. In his technique he becomes a paladin of early Modernism.

The second defining feature had to do with the guild-style organisation of Soviet society. An artist without a higher education had little chance of breaking through to the top. Weisberg studied painting at the studio of the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions where amateurs received some basic training. And therefore, could not qualify for the warm seats and large state commissions.

He was much loved for his painterly subtlety. For the fact that the optical mixing of complimentary colours on his canvas did not create an effect of ‘dirt’. For his mastery of dissolving the figure in space with the help of light strokes. In his early period, he was an epigone of the Russian Cezannist Ilya Mashkov (1881–1944) and his school, which Weisberg absorbed second-hand. Despite the ideological rejection of new Western painting, Cezannism was one of the acceptable manners for the Socialist Realists. Moreover, between 1958 and 1964, Sergei Gerasimov (1885–1964), an outspoken Cezannist, held the post of First Secretary of the Union of Artists of the USSR. In 1961, Weisberg was admitted to the Union of Artists.

The difference is that he did not paint any ideological themes. And he began to exhibit with the non-conformists. In the sixties, Soviet art was divided into the official and the unofficial. Weisberg’s position was to remain only an artist: he didnot become a dissident, but he exhibited with dissidents and at the dissidents’ venues. However, he also regularly participated in the traditional Autumn and Spring exhibitions of the Moscow Union of Artists. Since the early 1960s, he was a member of the so-called Group 9, and along with artists from this group, he often participated in group-wide official exhibitions. This was how his works found their way into two art markets simultaneously – that of state purchases and the private market, i.e. the one that was not controlled by the government. As a result, his first solo exhibition took place in 1975 at the Museum of Israel in Jerusalem. The artist's first solo exhibition in his homeland became possible only after his death in 1988, in the exhibition hall of the Moscow Union of Artists on Vavilova Street.