Davyd Burliuk Carousel. 1921. Oil on canvas, 33 x 45.5 cm. National Art Museum of Ukraine

Ukraine in the Eye of the Storm

The first proper survey of Ukrainian modernism in Western Europe is long overdue and is finally taking place amid a rise in awareness about a country whose cultural legacy is much misunderstood in part thanks to Western post-war art historians who clumsily wrote Ukraine out of the picture.

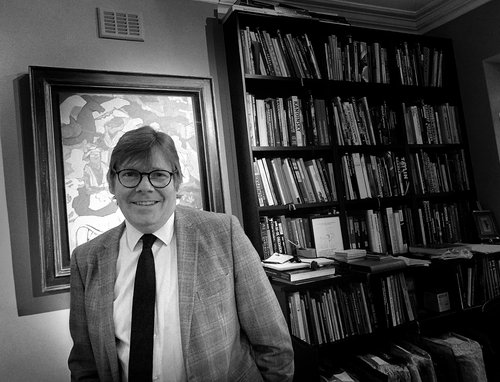

Most would have shied away from the prospect of mounting an international show of Ukrainian art at such a difficult time. But within days of the conflict starting, independent art historian and curator, Konstantin Akinsha was thinking about how to protect Ukrainian masterpieces in national collections. Yet what eventually became this exceptionally timely show ‘In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900–1930s’ was the culmination of years of study and research in similar fields. At Harvard, Akinsha studied the fate of the fabled Ukrainian Khanenko collection, dispersed during the Bolshevik Revolution and later Nazi occupation. He curated the critically acclaimed exhibition at the Neue Galerie in New York seven years ago which placed Russian modernist artists among their German contemporaries, redressing national imbalances and stymied perspectives in art history. A few years later, at the Ludwig Múzeum in Budapest, his adopted home for many years, he mounted a show of contemporary Ukrainian art which now seems exceptionally prescient, titled ‘Permanent Revolution’.

This current exhibition on Ukrainian Modernism could have been staged years ago, but I suspect it would have found little institutional support anywhere. Now, in the eye of the storm, Akinsha quickly found an ally in an art collector and philanthropist from one of Europe’s greatest collecting dynasties, Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza. The exhibition project was a natural fit for her, she had visited Kyiv in 1984 with her father who was planning a series of exhibitions around the Soviet Union. She has a proven interest in art from outside the mainstream — Eastern Europe and Russia was one cornerstone of the family collection reflecting the Hungarian nationality of its founder, Baron Heinrich and his son Hans Heinrich. With Francesca, there was immediately a synergy of purpose, she is a tireless art promoter with a social conscience, she had already experienced art in times of conflict during the war in the Balkans in the early 90s even though today her art activism is more focussed on the climate.

It is perhaps easy to take for granted the fact that the exhibition did happen boosted by the groundswell of political support and interest in the Ukraine in Europe. Yet that misses the reality: to assemble and facilitate such a show in the eye of the storm, is exceptionally challenging. Much of the artwork itself, comes from two state museums in Kyiv and it had a perilous journey to Madrid. As if on cue in some horrible twist of fate, on the day the truck was close to the Polish border en route to Spain, there was an accidental bombing close to the border in Poland by Ukrainian anti-missile weapons. The responsibility for transporting these works of priceless national value, which could have been damaged in transit, raised tough questions for the curators. Had they even gone too far? It was described in The Art Newspaper as the ‘largest-ever legal transfer of art from a war-torn country’. The border crossing from Ukraine to Poland was a moment of high cinematic tension, which thankfully ended with a smooth passage of the artwork to the Thyssen Museum in Madrid where they will be safely on show until late Spring 2023.

It was not all drama though. Some among the most outstanding works in the show only moved from one wall to another at the Thyssen which itself boasts excellent works by Ukrainian modernists thanks to the liberal taste of Hans Heinrich Bornemisza who in the early post-war era had an interest in German Expressionist art which expanded to include other modernist currents in Eastern Europe. I have never seen Voldymyr Burliuk’s (1886–1917) 1910 monumental study of a Ukrainian peasant woman with a cross around her neck, looking so sublime nor as at home as in this exhibition, evoking an elegiac portrait of a whole nation. The decoration behind the peasant woman and on her dress dovetails with her strong faith and sense of being a part of the land.

What becomes clear from the catalogue essays and the works in the show is that Ukrainian and Russian 20thcentury art is deeply differentiated. To use a few broad generalisations: Ukrainian art is more free; more decorative, less politically engaged; there is a focus on painterliness, which in part came from the southern light of Odessa and the school of painters there who aligned themselves with France. There is also the role which Ukrainians played in the story of the avant-garde; any history of futurism, whether focussing on the Russian contribution of Cubo-futurism, or a more traditional approach centred around Italy would be woefully incomplete without more than a passing reference to Oleksander Bohomazov (1880–1930), the Burliuk brothers and Oleksandra Exter (1882–1949).

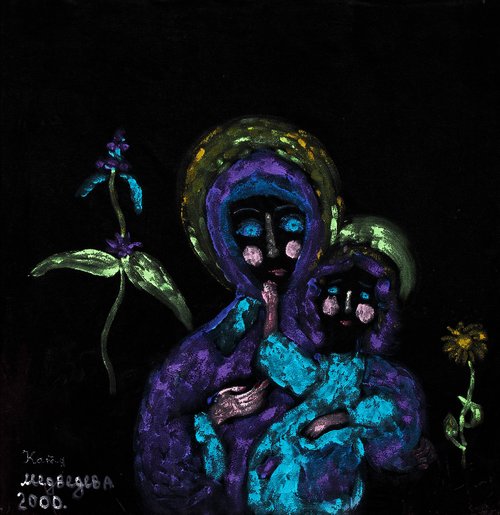

There are numerous highlights in this show. The unique voice of Vasyl Yermilov (1894–1968) whose memorial plaque marking the death of Lenin from the Ludwig Museum collection sits right at the crossroads of art and politics and feels like a signpost to late 20th century conceptualism. The exhibition includes Ukrainians in emigration, Alexander Archipenko (1887–1964), Wladimir Baranov-Rossine (1888–1944) and Sonia Delaunay (1885–1979), whose inclusion is an out-of-place epilogue. Such big names could have upstaged the real stars of the show, so from a curatorial perspective their inclusion was never going to be straightforward. Much is made of the Boichukists, artists who gathered around the painter Mykhailo Boichuk (1882–1937), most notably Anatol Petrytsky (1895–1964) and Victor Palmov (1888–1929) who revived the naïve and Byzantine art forms of medieval Kyiv-Rus. The exhibition shows the various sides of Petrytsky’s work, his forays into abstraction, his theatre work, for which he is best known, and includes his large scale 1924 painting ‘The Invalids’ which won the artist a medal at the Venice Biennale in 1930.

The exhibition and catalogue, which is far more extensive than the show itself, raise questions about the categorisation of some of Ukraine’s artists in art history, such as Oleksandra Exter, who is often viewed as a leading figure in the Russian avant-garde and deemed to be Russian although she only lived in Moscow for three years and everyone visiting her Paris studio delighted in the Ukrainian folk art, embroideries and decorative pots and plates she surrounded herself with there. It also invites debates over how to spell the names of artists. In 1933 Stalin clamped down on the Ukrainian usage of the written Latinised ‘g’ which sounds out softly, more like an ‘h’ in English. Today – as a direct result of the conflict — there is a new preference to reflect these Ukrainian spellings in the English language, hence for example the spelling of Oleksander Bohomazov. The fact that the Russian and Ukrainian modernist artists who we associate with the avant-garde were so fluid, creates an open field with counternarratives which will make Ukrainian, Russian and world art history more rich, diverse, and inclusive. These are democratizing art historical and curatorial approaches which are very much of our time. As with a lot of post-war art history, somes record need to be made straight. What is written about the Russian avant-garde came from Camilla Gray’s ground-breaking book on the subject ‘The Russian Experiment in Art 1863–1922’ which was published in 1962 creating a story which basically assumed the Russian avant-garde as a wholly Russian phenomenon. From then on in, and during the cold war, the West’s love affair with the Russian avant-garde was fuelled as much by politics as well as perhaps a lack of all the facts, understandably so as much was inaccessible, it was only a story half told, which perpetuated myths.

There is a lot more work to do for Western art historians and art experts in museums and the commercial field at reimagining the avant-garde to write the Ukrainian contribution into art history fair and square. Russian culture was so rich and dominant, at the time when the cultural centres of Kyiv (and similarly Vitebsk) were part of the Russian Empire, when modernism was born. You cannot change history. Yet there is a place now for more nuanced and questioning approaches.

Detractors of the exhibition will say it was put together in haste and focus on what is missing in what otherwise could be a more complete survey, yet this would be churlish; some of the best and most original art exhibitions have raw edges, because they break new ground. They are less exhibitions, more cultural happenings and they often leave us wanting more, which this show does. Doubtless, to mount an exhibition of Ukrainian modernism amid the worst conflict in Europe since 1945 itself could be viewed with suspicion as a political step and it will surely receive more publicity than it might have because of this. It has captured the imagination of the Western press at large. As Francesca Thyssen-Bornemeszia put it it the exhibition is a ‘symbol of defiance’.

There is that well-worn phrase which has been popularised (and claimed at different times) by both Spanish and English writers: ‘all’s fair in love and war’. On a wave of support for the Ukraine in Europe, this exhibition was made possible, yet in the end taking it politically is to lose the point of what is at heart a terrific, heart-warming, mind-altering show about Ukrainian art.

In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900–1930s

Madrid, Spain

November 29, 2022 – April 30, 2023