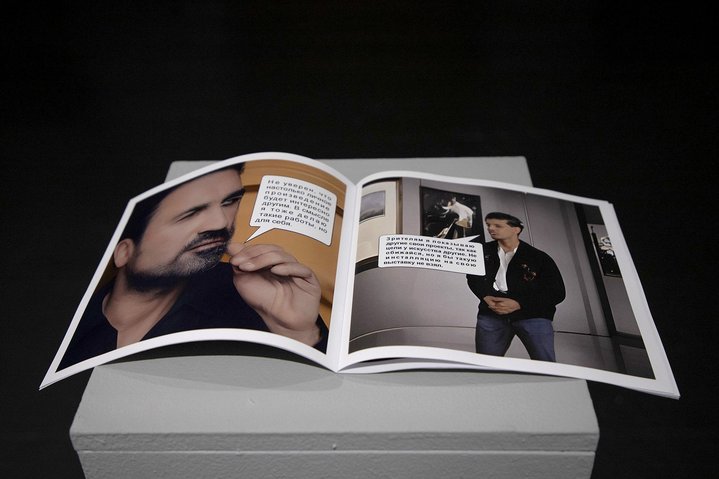

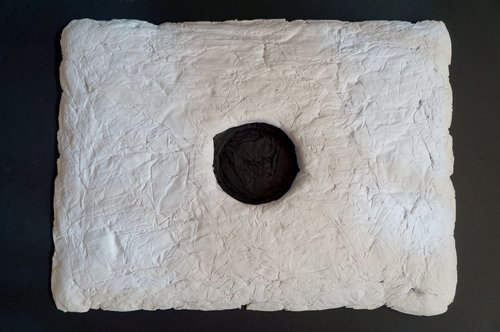

Kirill Gurov. Territory. Exhibition at the OSSI ‘MI’, Samara

Time of crisis brings new self-organized artist initiatives in Russia

During 2022 there has been an emergence of several new important creative initiatives within Russia as a direct response to the deep social and cultural existential crisis experienced by the nation at large.

Samara is a cultural city on the artistic map of Russia where two new art spaces have appeared since February this year. They are projects by local art entrepreneurs and husband and wife team, Ilya and Snezhana Mikheev, who established an apartment gallery called ‘Outskirts of Samara Contemporary Art MI’ also known by its acronym OSSI ‘MI’. This is no light or airy space. You could call it a black cube, suggesting a different kind of artistic activity. In September one of the Mikheev’s neighbours placed an old, unopened suitcase in the centre of the gallery, from which photo albums, documents and autobiographical notes were scattered on all sides suspended from threads. In November, Voronezh-based artist Mikhail Dobrovolsky exhibited a series of surrealist paintings depicting a cannibal's dinner.

A few months later, the Mikheevs opened their second space, called the Starukha Art Zone (Starukha means ‘Old Woman’ in English). If OSSI ‘MI’ is essentially a traditional gallery in a residential area, this second space is more out of the box. Starukha is a popular district in the city which takes its name from one of its streets, ‘Stary Zagory Ulitsa’. The new venue is in the basement of a residential building, next to ‘Red and White’, a chain of affordable Russian off licences. The organizers like to use it as a reference point for new visitors (‘it’s the first door on the left of the off-licence’). To attend an art event at Starukha you need to pay an entrance fee or sign an agreement that you will come again to the next art event. However, if you do not come, you will be fined 500 roubles or blacklisted and not allowed in again.

This artist-run space is literally ‘10 square metres of art’, as the Mikheevs put it. It is a training ground for artists who manage it themselves without a curator. There are no established values, no obvious markers of taste, there are no openings with drinks or other usual trappings of an art institution. There is just one focus at the centre of their mission. The Mikheevs support ‘arte povera’ in its broadest possible definition, lifted out of any historical context and at Starukha there is a nonstop open call on repeat button. Its goal: to attract ‘arte povera’ in whichever form it may manifest itself. There is an appetite for openness and experimentation. It’s all about art which is excluded from the art market and there is no place for commercial art sales.

The first exhibition in the space was a playful critique of the outdated post-conceptualist approaches characteristic of the leading Moscow art schools such as the ICA founded by Josef Backstein and Anatoly Osmolovsky’s (b. 1969) (declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities) Baza Institute. An alumnus of the latter, Fyodor Dubrovin (b. 1985), photographed Baza’s educational space and instead of printing out the photographic images, he printed out the text of the properties and code taken from the photos on the hard drive of the computer. These 'snapshots' were put on display at Starukha on 24th of July, and a week later the artist put on display similar 'photographs' which he took at Starukha’s exhibition space. At the beginning of September, a local artist, performing under the pseudonym Pusto (Empty), invited visitors to a game of hopscotch. She drew the numbers in boxes laid out in the traditional way on the floor. At the end of October, local artist Anton Weiss (b. 1997) covered three walls and part of the ceiling with abstract works, using a mechanical process, hoping to arouse emotions among the viewers.

In October, a self-organized, curatorial group called ‘Temporary Solution’ established by Ksenia Markelova (b. 1994) and Nikita Perfiliev appeared in Ekaterinburg. Mounting exhibitions in different locations around the city they asked themselves the question ‘how to live?’. Until 25th of December, the state Metenkov House Museum, is hosting their project ‘Turning Appearance into a Swamp’, which consists of work by local artist Svetlana Spirina (b. 1990) and Ksenia Markelova herself. The exhibition intends to evoke a state of confusion; there is no explanatory text. The visitors are meant to walk around. As the curators explain: "we propose to follow the path of the artists themselves, to immerse ourselves in the place in which we find ourselves. Dive into the swamp, try on a new skin. Compare it with your own." ‘Temporary Solution’ is planning further similar interventions in a host of different spaces.

Also in Ekaterinburg, over the summer months a ghost gallery called ‘Guest’ was created in Anastasia Bogomolova’s (b. 1985) studio at the local National Centre for Contemporary Art, now a branch of Moscow’s Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, where three exhibitions were held. The inaugural show was an installation ‘Aphasia’ by Anastasia Pishygina, an artist from the nearby town of Verkhnyaya Pyshma. It consisted of two tents, each emblazoned with a system of signs which is impossible to read, referencing the loss of language because of censorship and the general degradation of the public field. Since the departure of its founder to an artist’s residency in Sweden, the gallery has recently evolved into ‘Guest’ residency, and Ekaterinburg artist Alyona Gurieva (b. 1993) is now living and working there.

This summer Moscow saw the formation of a new group called PNI, an acronym which normally stands for either the destruction of plant form or punitive psychiatry but here refers to ‘practices of non-spectacular art’. The word ‘pni’, meaning tree stubs in Russian doubles as an acronym for Psycho-Neurological Residential Facilities, the infamous system of state-run, prison-like institutions for the mentally ill. In August they staged an intervention at GES-2 where members placed their ‘non-spectacular’ works into the display of the existing show. The artists printed booklets imitating GES-2’s corporate style, adding misprints into the descriptions of existing exhibits, and placed objects or images that extended the artworks on display. Ilya Kachaev (b. 1999), an artist and member of PNI, who organised fake booklets to be sneaked in and the installation of works in situ, was fired from GES-2. The objects themselves were taken off view, gathered up and are currently in the institute’s archive.

The intervention attracted a lot of media attention before being quickly forgotten, however the PNI collective is continuing its activities. They are currently holding an exhibition at Vinzavod called ‘Coordinates’, a large scale, total installation stretching over the whole territory of the art cluster, this time with all the relevant permissions. The project consists of stickers and small canvases placed on vertical and horizontal surfaces throughout the complex. The installation map is also superimposed on a fire safety diagram. The project is centred around the recording of a horn from a Soviet young pioneer camp, which plays in Vinzavod’s courtyard, marking the main milestones of the day's routine.

Another new self-organized art initiative in Moscow, gallery K320, takes its name after the number of the room in which it is located. Artist Anastasia Belaya (b. 1998), a student of the Baza Institute, moved into a two-room space earlier this year, with one room for her studio and the other an exhibition space. But it evolved quickly because now there is barely any space left for a studio as all her energy and time is taken up by incoming projects. At the end of February, Belaya urged artists and curators in general not to give up making art and offered up her as yet unopened gallery as a free space. An open call was even announced, which sounded like a manifesto: ‘Art is not for drinking champagne at receptions. Art is not for entertainment. Art is not for distraction and escape into unreality! ... Art saves, supports, helps, heals, prepares us for a better world without war and pain’. There have been exhibitions held in the gallery, currently co-curated by Belaya and Alexandra Boyeva (b. 1992), since March. In June, there was a series of projects curated by Svetlana Baskova (b. 1965), director of Baza, and art critic Yegor Sofronov: solo exhibitions by Sasha Knyazev, Alexander Golynsky (b. 1987) and Andrey Shepel (b. 1989) were organised as part of a long-standing collaboration. The gallery also hosted a screening of ‘The Lightest Darkness’, directed by Diana Galimzyanova. In July, art historian Alexandra Boyeva, who curated the group exhibition ‘Ground Zero’ in March at K320 joined its team as co-organiser. In the second half of the year, projects began to take place at K320 with twice as much force and more regularly.

On the 10th of December a new space called the ‘Plague. Office’ opened in Kazan, a launch which had already been some time in the planning. On the one hand, it is a project room that spun off from both the Plague space and the Krasnodar collective of the same name. One of the creators of all these artistic entities, Artur Golyakov (b. 1991), moved to Kazan long ago, but still maintains projects in Krasnodar, a city in the South of Russia. However, on the other hand, it is not just a branch of the Krasnodar project. For in Kazan, Golyakov has brought local artists into the initiative, most notably Zukhra Salakhova (b. 1997), who co-founded Plague.Office. This new platform will work directly with the local Kazan context as well as seek wider, international connections where possible.

OSSI MI

Samara, Russia

Khz Starukha

Samara, Russia

Temporary Solution

Turning Appearance into a Swamp

Ekaterinburg, Russia

PNI

Moscow, Russia

K320 Gallery

Moscow, Russia

Plague Office

Kazan, Russia